Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Chinese companies will have to start paying into employee pension plans this week, as Beijing pressures business to pick up the bill for an ageing population.

Many workers have long agreed to let employers off the hook for what should be mandatory pensions contributions, in exchange for higher salaries upfront.

However, China’s Supreme People’s Court last month outlawed such informal practices from September. Wu Jingli, a deputy chief judge, said its ruling would prevent business owners from exploiting their bargaining power and “actively address the issue of an ageing population”.

China’s pension system has come under strain in recent years as the working-age population falls and people live longer.

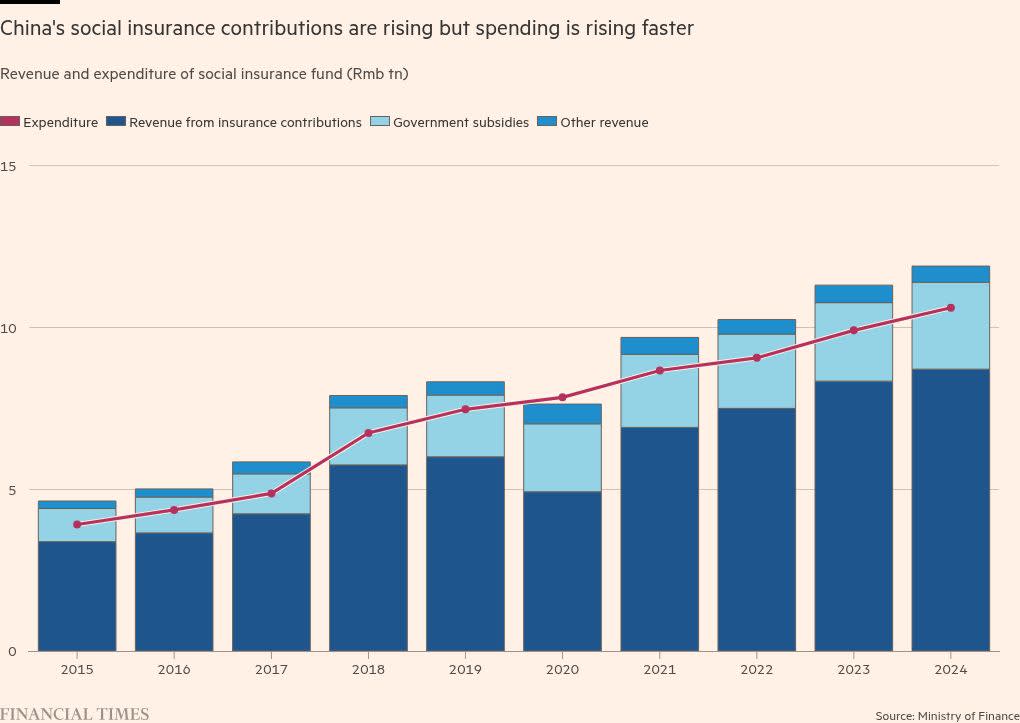

Payments into the central social insurance fund — buoyed by government subsidies — increased 5.2 per cent in 2024 to Rmb11.9tn ($1.7tn). But overall pension payouts last year rose at a faster rate of 7 per cent.

Meanwhile, only one-third of China’s working population of 734mn made full social insurance contributions for 2024, according to Financial Times calculations based on official statistics.

Experts and businesses have warned that sudden enforcement of contributions would hurt employers, who claim they cannot cope with the additional costs amid slowing economic growth and tepid consumer spending.

Jacky Zhou, the manager of an eatery in Shenzhen that specialises in luosifen — a river snail noodle soup from south-western Guangxi region — said rising labour costs had already forced his employer to shutter two outlets. Now, the local social security bureau was demanding unpaid contributions from the last six months of 2024, he said.

The company was planning to retreat to Nanning, the capital of Guangxi, where labour and rental costs are considerably lower.

“For a small business, breaking even is good enough these days,” Zhou said. “But when you’re hit with a sudden rise in cost like this, it becomes too exhausting just to keep the doors open.”

Historically, the gap between pension contributions and payouts has been covered by the government.

But local governments have been under growing fiscal pressure after a collapse in land sales reduced one of their primary revenue streams. The central government is also paying for stimulus programmes — such as subsidies for births and consumer goods — rolled out this year.

Yao, a manager at an auto parts manufacturer in eastern Zhejiang province, said he now had to pay Rmb770 for each of his dozen employees, on top of their monthly salaries of Rmb4,000, which “increased costs significantly” for his business.

The workers, who needed to contribute Rmb385 of their salaries, “didn’t want to pay either”, he said.

Some businesses have responded by cutting roles and hiring part-time staff, who do not qualify for social insurance. Others, including McDonald’s, are rehiring pensioners, who are exempt from contributions.

In a statement, McDonald’s said it had “a flexible and diverse employment model”, adding that “the recruitment of retirees has existed for some time and the company provides compensation and commercial insurance in compliance with Chinese government regulations”.

In Shanghai, a Japanese canteen owner surnamed Yu said he was reclassifying workers’ contracts as part-time, a technical move that would allow them to earn the same money while avoiding pension payments. “It’s the only way to circumvent mandatory social security contributions,” he said.

Yu noted that, as pensions were tied to workers’ household registration, paying into the system made little sense for migrant workers. “Most of them will not stay in Shanghai for 25 years to get the pension, so they would rather receive more cash,” he said.

“China will have to juggle improving the social safety net and labour rights with the unintended consequence of a temporary reduction in full-time employment,” said Kelvin Lam, senior China+ economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

He Bin, former deputy director of the public policy research centre at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, called for lower social security contributions to avoid burdening businesses and workers.

“Enforcing high contribution rates would eliminate a crucial economic cushion [for businesses],” he said. “Blaming corporate greed for non-payment of social security contributions is mistaking the symptom for the disease.”

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong