Gao jia, a seven-year-old American from New York, might not start his second year at school this September. During a family visit to China last August, his father, a Chinese artist called Gao Zhen, was arrested for “slandering heroes and martyrs” (Mr Gao is the elder of the well-known “Gao Brothers”, whose sculptures often mock Chairman Mao). The boy has not been accused of wrongdoing; neither has his mother, Zhao Yaliang. But in China, family members can be punished for the alleged sins of a relative. Ms Zhao has been put under an “exit ban” that stops her from leaving the country. With both his parents stuck in China, Gao Jia is also unable to leave.

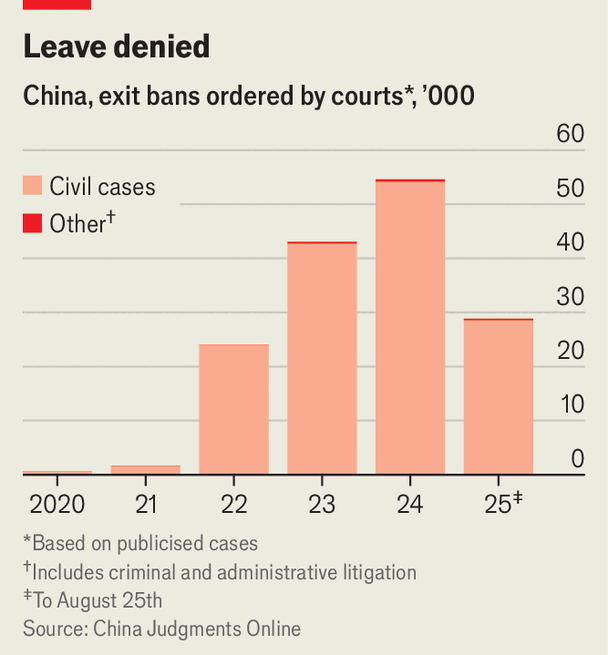

Many countries use exit bans to prevent people accused of crimes from escaping justice, but the bar is usually high. In China they are slapped on everyone from dissidents to foreign executives involved in business disputes—as well as family members who are not even wanted for questioning. Many exit bans are not made public, so it is hard to tell how many people are affected. But courts seem increasingly willing to impose them. An official database of court judgments that have been made public (many are not) contains records of more than 54,000 bans last year, up from some 24,000 in 2022 (see chart). Anecdotally, it appears that a growing number of foreigners are being targeted.

In the database, almost all cases involving exit bans relate to civil disputes, not criminal activity. The bans it documents are often ones requested by creditors of a struggling business who want the owner to stay in the country until the firm’s debts are settled. But an exit ban can be applied for by “virtually anybody”, says John Kamm of the Dui Hua Foundation, an American ngo. “You have no idea that you are the one who might be banned…You know nothing.” An expanding legal net is increasing the chance of ensnarement: China now has at least 18 laws allowing exit bans. Five have been passed since 2018, including new legislation relating to corruption, fraud and telecoms scams.

The way bans are applied is opaque. They can only be imposed on family members if they are needed as witnesses, but in practice relatives are often barred from leaving for no apparent reason other than to put pressure on someone involved in a court case. Ms Zhao only found out she was stuck in China when she and her son tried to go through passport control at an airport. Once in place, bans can last years. It is very difficult to contest them.

They are adding to strains in Sino-American relations. In April an employee of America’s commerce ministry was banned from leaving China after being interrogated by officials from China’s spy agency, the Ministry of State Security, according to the New York Times. In July Wells Fargo, an American bank, suspended all business travel to China after one of its employees, a Chinese-born American citizen called Mao Chenyue, was prevented from leaving the country (China’s foreign ministry has said she is involved in a criminal investigation, without giving further details). Dui Hua estimates that more than 30 Americans in China were subject to exit bans last year.

Some of these cases may relate to China’s stepped-up efforts in recent years to stamp out graft. When bosses of state-owned enterprises are being investigated, exit bans are sometimes imposed on people who have had dealings with them, including foreigners wanted as witnesses. Such people should be wary of this risk, says James Zimmerman, a lawyer in Beijing and former chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in China.

For now, Gao Jia is going to a primary school in Yanjiao, a town near Beijing. Since May, all letters to him from his father have been withheld by Chinese officials, according to his mother, Ms Zhao. Her husband’s trial is expected to begin soon, she says, and could result in a three-year sentence. Ms Zhao sees a possible silver lining, however: when the proceedings are over, she hopes she might be allowed to return to America with her son. ■

The Economist