Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Taiwan is set to vote on whether to return to nuclear energy just three months after shutting down its last reactor, as concern mounts over how to supply enough power to keep its world-leading chip sector growing.

The vote also highlights the country’s challenges in securing stable energy supplies to survive a potential Chinese blockade.

Launched by the two opposition parties, which hold a legislative majority, a referendum on Saturday will ask voters if they support restarting a reactor at the Maanshan plant in southern Taiwan, provided regulators do not find safety concerns.

The vote comes as soaring electricity demand to serve artificial intelligence computing — just as governments around the world seek to cut carbon emissions — has prompted a global revival of nuclear energy.

In the US, President Donald Trump is aiming to quadruple nuclear energy capacity in the next 25 years. Germany’s new government appears intent on revisiting the country’s nuclear “exit”.

Even Japan is reopening reactors and planning the construction of new ones 14 years after the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Many foreign observers have urged Taiwan to follow that trend, arguing that its dependency on imported gas, coal and oil for more than 95 per cent of its energy makes it highly vulnerable to a Chinese blockade. Beijing claims Taiwan as part of its territory and has threatened to take it by force if Taipei refuses unification indefinitely.

“Energy is the weakest element in Taiwan’s resilience,” said Mark Cancian at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think-tank in Washington, who co-authored a war game last month that simulated a Chinese blockade of Taiwan.

“Taiwan needs to pay special attention to that,” he added, suggesting that it could do so by “extending the life on its existing nuclear power plant and also by hardening its electrical system”.

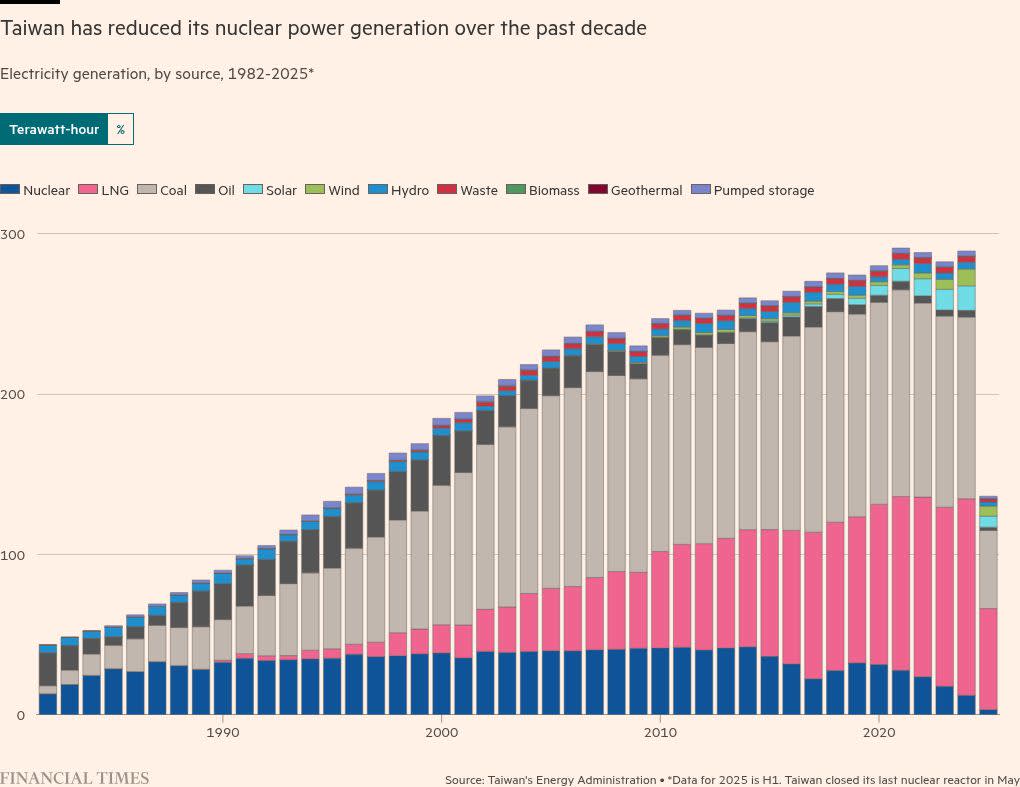

Nuclear power generated more than half of Taiwan’s electricity in the 1980s, but in May state-owned utility TaiPower switched off the final of six reactors after its 40-year operating license expired. That made Taiwan the third country to close all its nuclear power plants, following Italy and Germany.

President Lai Ching-te celebrated the step as historic realisation of his Democratic Progressive party’s decades-long goal of a “nuclear-free homeland”.

Last week, he told a DPP meeting that he would oppose the referendum to restart the plant. “We will vote against it together,” he said.

That stance is part of the party’s ideological roots. Fears about Taiwan’s frequent earthquakes and anger that the then-authoritarian government stored nuclear waste on an outlying island without informing its Indigenous population sparked an anti-nuclear movement in the 1980s. These activists were at the heart of the pro-democracy groups from which the DPP emerged.

The 2011 Fukushima disaster broadened public opposition to nuclear power, leading the government to back an exit from the energy source. Two years after the DPP returned to power in 2016, the government started successively shutting down reactors.

But Taiwan has struggled to manage a transition to renewable energy at the same time that it has cut down nuclear capacity. Renewables accounted for only 13 per cent of electricity generation in the first half of this year, far behind the government’s target of 20 per cent. LNG was Taiwan’s biggest source of power generation at 46.2 per cent, followed by coal at 35 per cent.

Meanwhile, power demand is soaring on the global AI boom. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co, the world’s largest chipmaker, which already uses 12 per cent of Taiwan’s entire electricity output, is also rapidly expanding capacity.

Power cuts have become more frequent as TaiPower has tried to modernise its ageing grid. To stem the utility’s mounting losses, the government has been raising power prices that were long among the world’s lowest.

Those strains have helped shift public attitudes towards nuclear energy. According to the non-governmental Taiwan Institute for Sustainable Energy Research (TAISE), 66.1 per cent of Taiwanese now support using nuclear energy to achieve the goal of net zero emissions by 2050, up from 58.3 per cent in 2024. Only 33 per cent held environmental concerns over nuclear energy, less than for coal, oil and gas.

While voters have warmed to nuclear power, appetite for extending the lifespan of a 40-year-old reactor is less strong, according to the TAISE. Even Lai has indicated openness to new-generation nuclear power solutions, though he remains opposed to restarting the old plant.

The result of the referendum will only be valid for two years, however, meaning that even if a majority backs a restart, the government could in effect ignore it, if safety inspections and other procedures exceed that timeline.

In contrast to the international concerns about Taiwan’s energy security, the domestic debate has centred on air pollution and economic growth. “Taiwan has paid a high price for phasing out nuclear,” said Tung Tzu-hsien, the founder of contract electronics manufacturer Pegatron, in a televised debate on the referendum last week.

Tung, who sits on a committee that advises Lai on climate policy, blasted Taipower’s move to restart two coal-fired power plants to plug the power gap as “absurd” and blamed the DPP for pushing Taiwan to the “bottom of the class” in global carbon emissions.

He also warned that Taiwan’s polluting energy balance could undermine its technology exporters’ competitiveness as major markets start levying carbon taxes.

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong