Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

Banks and companies in emerging markets outside China are selling international bonds this year at the fastest rate since 2021, as the premium investors demand to own their debt over US Treasuries has fallen to its lowest since 2007.

Such borrowers issued at least $250bn in bonds between January and July, a pace that will bring them close to matching the full year volume of 2021, when issuance boomed in the Covid-19 pandemic, according to JPMorgan and S&P Global datasets.

Ebullient global stock and debt markets are leading companies to take advantage of falling borrowing costs, as investors bet that US President Donald Trump’s tariffs will cause less damage than feared to the global economy.

Despite Trump’s increasing willingness to wield tariff threats against big developing nations such as India and Brazil, buyers of global bonds are growing more confident that US interest rates will fall in the coming months as Trump puts pressure on the Federal Reserve.

“The market is beginning to price in a more accommodative Fed . . . many companies that were on the sidelines are revving their engines,” said Alan Siow, co-head of emerging market corporate debt at asset manager Ninety One.

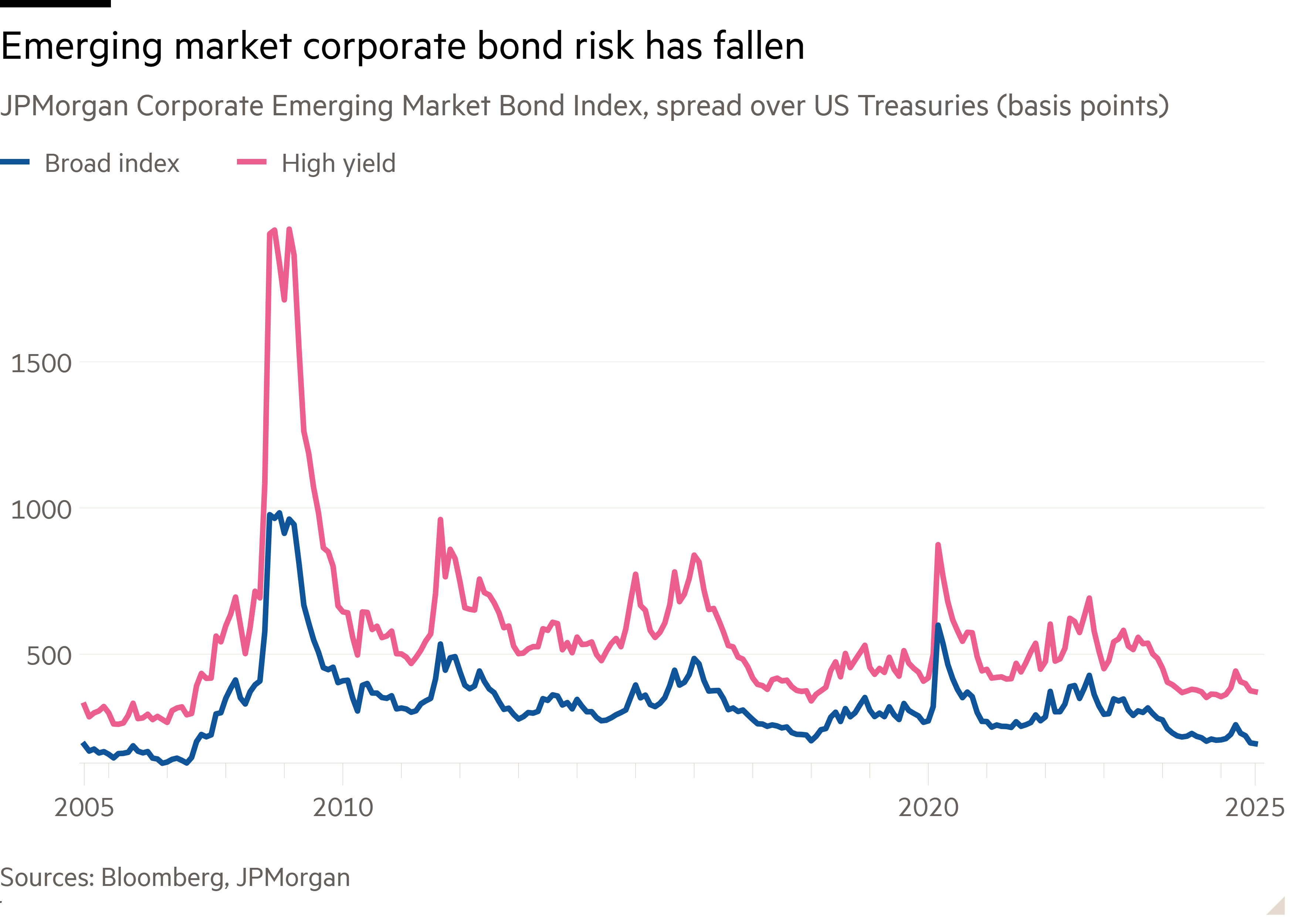

The overall yield on a JPMorgan benchmark index of corporate emerging market bonds is still about 6 per cent, but with US bond yields rising this year, its “spread” over 10-year Treasuries — the premium investors demand to hold riskier debt — has fallen to less than 2 percentage points for the first time in nearly two decades.

The spread over Treasuries of riskier high-yield emerging market corporate debt has also narrowed.

JPMorgan analysts have forecast that 2025’s total for international corporate debt issuance outside China will amount to $370bn, just short of the total in 2021.

Including Chinese issuers, the estimate rises to $433bn, but debt repayments are expected to be larger than this and have already outweighed new supply this year by $8bn.

“The two strongest years in the history of emerging market corporate debt supply were 2020 and 2021” and this year is on pace to track the latter, but debts from the pandemic boom in issuance are also coming due, Siow said.

“What is beneath the surface here is that, year to date, the net supply is negative,” he said, after recent years in which global interest rates were high and companies ventured less into markets to refinance debt.

China once dominated international corporate bond sales in emerging markets, before a debt crisis swept through the country’s property developers from 2021 and borrowers turned to onshore markets where interest rates have plunged.

At more than $160bn so far this year, governments in emerging markets are selling international debt at a faster pace than in 2020, a record year for issuance, according to JPMorgan data.

Saudi Arabia’s government and banks have been particularly big sellers of dollar debt this year, as the kingdom has turned to borrowing to finance a surge in domestic investment and to ride out a lull in oil revenues.

Mexico’s government recently steered a bumper $12bn bond issue to anchor a partial bailout for Pemex, the state oil company.

Despite Trump’s recent threats of 50 per cent tariffs on India and Brazil over political disputes with both countries, “I would describe the market as surprisingly sanguine” on tariffs, Siow said.

“These announcements are scary if they come to fruition, but the market is looking through it,” partly because of the “devil in the detail” of exemptions for key exports to the US, he added.

Investors have calculated, for example, that a US headline threat of 25 per cent tariffs on Mexico would in effect be below 10 per cent on average when factoring in the quantity of goods subject to lower rates under the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement trade deal.