Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is the author of ‘Chip War’

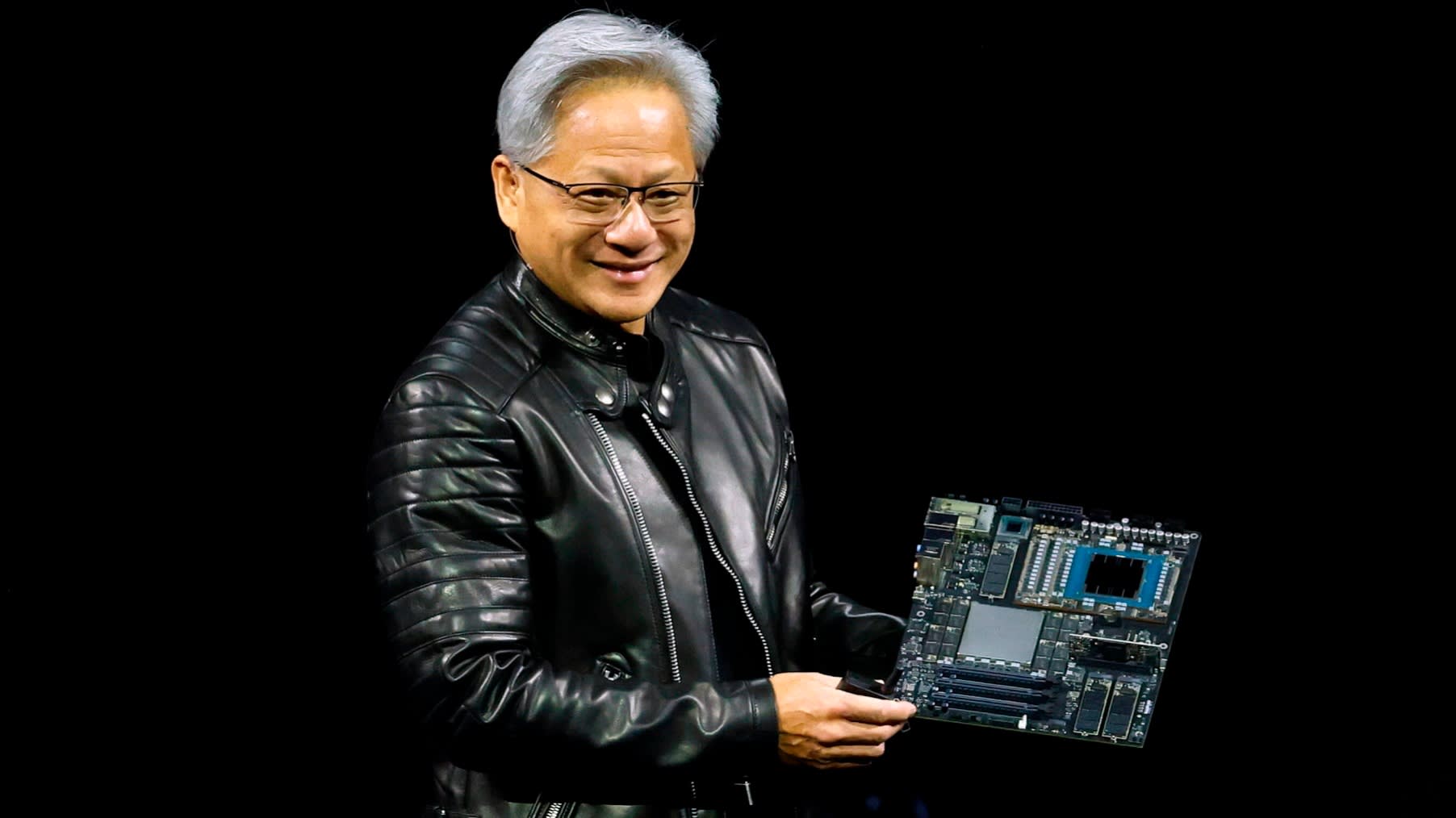

Shortly after US President Donald Trump changed his mind last month and decided that there was, in fact, no security risk in allowing Chinese customers to buy Nvidia’s advanced H20 artificial intelligence chips, Beijing appeared to hesitate. Trump’s reversal looked like a straightforward win for China. Yet Beijing ordered its regulators to investigate whether Nvidia’s chips have “loopholes and back doors”.

Now that Nvidia has agreed to pay 15 per cent of its Chinese H20 chip sale revenues to the US government, it can restart sales — but first it must convince Beijing that its chips do not pose a security risk.

China’s investigation into Nvidia chips is a reminder that the US president isn’t the only world leader with a penchant for capricious decision making. But Beijing’s fear of back doors that enable unauthorised access cannot be brushed aside as simply the product of its paranoid political system.

US Congress is debating the Chip Security Act, which would mandate the commerce department to explore use of geolocation to crack down on smuggling of restricted AI chips and servers. It would push companies to use location verification and report suspected export control violations.

The legislation aims to address a contradiction: the US commerce department’s Bureau of Industry and Security has been trying to enforce export controls on advanced technology using old-fashioned investigative methods that would have been familiar to Sherlock Holmes. It has a single enforcement officer in all of south-east Asia, the region primarily responsible for funnelling illicit chips to China. Geolocation tracking could make up for this. Perhaps the commerce department can use Trump’s new 15 per cent tax on chip sales to fund this.

In an era when practically every consumer device has a GPS tracker, export controlled chips stand out for not emitting location information. Or do they? Debate over the legislation has unearthed the fact that AI chips often transmit large volumes of data already. Complex chips like those used in AI data centres provide data called telemetry, which describes details such as their utilisation, temperature and power consumption. Companies like Nvidia and AMD advertise these telemetry capabilities as enabling better data centre management, letting cloud computing companies optimise workflows and identify servers that need repair.

The chip location verification that is under discussion would build on these existing capabilities. The location of a chip could be confirmed by tracking the time it takes a signal to travel from it to a server in a known data centre. If the signal arrives sooner or later than expected, the chip probably isn’t where it is reported to be.

Location verification is different from a kill switch or a back door, which leading chip companies deny exist and reject as a bad policy. Yet US chip companies also highlight the work their own support and software do for chips they’ve already sold. The US has already restricted western companies from servicing semiconductor manufacturing equipment previously sold to China, as part of an effort to degrade the country’s chip manufacturers. It’s easy to see why China’s security services are nervous about American-made servers in their AI data centres, too.

Beijing no doubt has always suspected that US-designed chips have deliberate back doors, though there is no public evidence for this. We do, however, know plenty from the public domain about apparently accidental design flaws in past chips that were discovered to have unmasked encryption.

China’s leaders cite security as a key rationale for their decade-long drive for chip self-sufficiency. Yet this dilemma is not unique to China or even to chips: it is the result of increasing connectivity in all sorts of complex machines. Washington had a kill-switch crisis of its own last year, when US intelligence reportedly found extra modems on the Chinese-made cranes that move containers from ship to shore in US ports. If every ship crane could be shut down from Beijing, the US logistics system would grind to a halt. Similar fears have led the US to ban Chinese components from connected auto systems.

Nearly every piece of complex equipment — from cars to construction tools to medical devices — can report performance data back to a central server. This enables everything from software updates to predictive maintenance. Remote access and semi-autonomous operation are key to the productivity improvements the tech sector promises. The question is who else can access this data. The more data flows around the world, the more security concerns this will raise.