Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Chinese business & finance myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is an FT contributing editor and writes the Chartbook newsletter

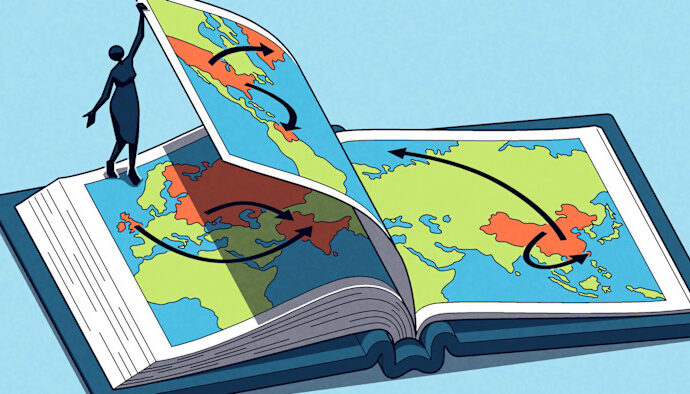

We used to know what the future of a globalised world looked like: cosmopolitan cities like New York, Paris, London, Hong Kong. These places had national character but blended together people, ideas and money from all over the world.

Many were once capitals of far-flung empires. Some, like London and New York City, had been hit hard by economic restructuring in the 1970s. They were re-energised and transformed by global growth.

The unstoppable trend of globalisation would inevitably produce more such places, or so the theory went. Digital networks and global air travel would knit them together.

The early 2000s were the high point for this horizon of the future. The great cities of Asia — Shanghai, Shenzhen, Beijing but also Mumbai and Bengaluru — joined the list of “global cities”. Shanghai’s skyline became recognisable around the world.

Then, the 2008 financial crisis snapped the association between growth and trade. GDP went on growing, trade as a share of GDP levelled off. Banks pulled back. European finance retreated. The Covid lockdowns of 2020-2022 delivered the coup de grâce to free-range globalisation.

If you visit China today, you will see something that was not on our radar two decades ago: mega cities of giant scale with tens of millions of inhabitants, spectacularly modern technology and infrastructure, deeply connected to the world economy but virtually empty of foreign inhabitants.

Foreigners make up 0.3 per cent of the population of Beijing. Of the 20mn inhabitants of Chengdu, the capital city of Sichuan province, the foreign population comes to a mere 0.08 per cent.

The signs are that we overestimated the force of globalisation in creating the characteristics of past global cities and failed to account for the particular circuits of money, people and ideas that were shaped by the legacies of empire.

Large rich economies, even those that engage intensively in trade, like Japan, have never had very large shares of trade in GDP. This holds for the US and the EU too. Discounting trade within the EU itself, Europe’s trade share with the world is an unremarkable 23 per cent.

China’s size gives this logic even greater force. As it consolidates its position as the largest productive system the world has ever seen, we should expect the world economy to matter to it increasingly less.

In generalising the idea of globalisation, we underestimated the networks of language and culture that defined long-range mobility. English, Spanish, French and Portuguese — the western imperial languages — served to channel and map routes of global movement. They made places like Rio, Buenos Aires, Sydney and Hong Kong.

The Sinosphere has its own cultural-linguistic logic. The Chinese language erects huge barriers to in-migration. But, at the same time, command of simplified Mandarin creates a shared culture for at least one-eighth of humanity. That opens the path to mass migration. Beijing may not have many foreign inhabitants but almost 40 per cent of its population has recently arrived from other parts of China.

Likewise in India’s tech hub Bengaluru, the foreign population is tiny but more than half of the city’s inhabitants are migrants from the rest of India.

These are not global cities as once imagined, but they are hubs and nodes in large and innovative societies that account for an increasingly large share of the world economy.

The online life of their citizens further exemplifies these trends. The denizens of China’s mega cities, like their counterparts everywhere, live on smartphones, consuming round the clock flow of news, gossip and the essential services of daily life, all exclusively in Mandarin.

The Great Firewall separates this world from the west. But linguistic hurdles and the gravitational pull of China’s social media system also naturally enclose the Chinese internet. Even if you choose to use a VPN and a translate app, who has the time and energy to keep up with another digital world of this intensity?

When the Chinese leadership launched its vision of “dual circulation” in May 2020, it was seen as a geoeconomic master plan for competition with the US. China would build a robust circuit of domestic consumption and innovation while leveraging a separate circuit of international trade. Increasingly, however, it looks less like policy and more like the description of a new mode of global economic development.

Instead of mixing and fusing the world in the melting pot, China’s cities are giant national and regional centres, interacting intensively with the wider world but at arm’s length.