Taiwan’s main opposition Kuomintang party has been on a roll. Since becoming the largest party in parliament early last year, the KMT has used its position to obstruct President Lai Ching-te’s government at every turn.

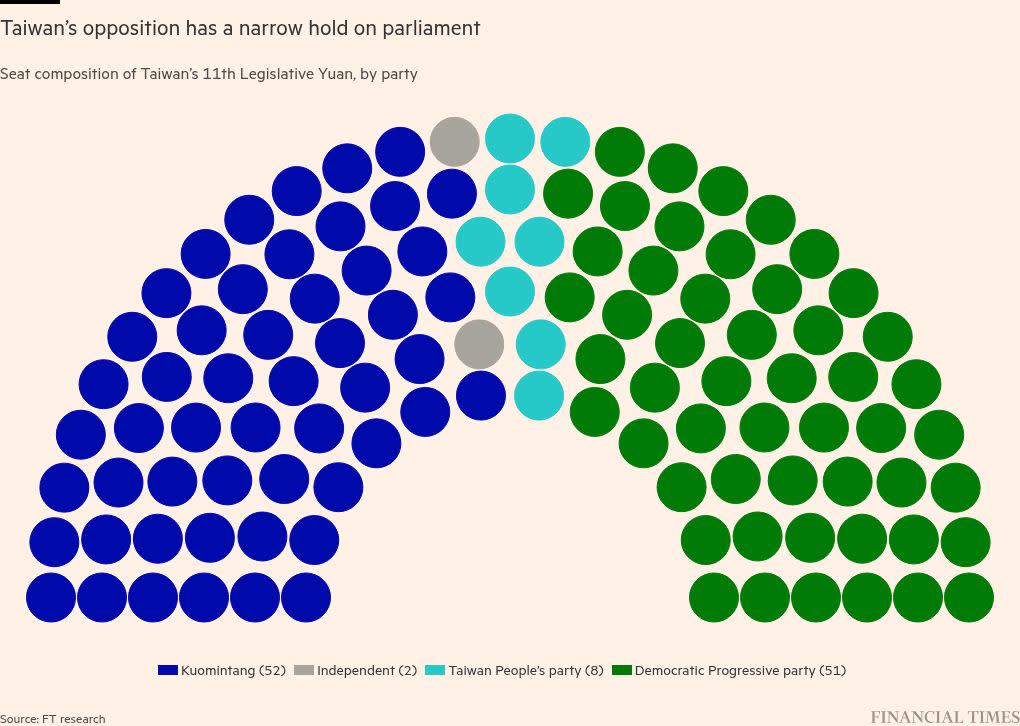

Now, it faces a reckoning: from July 26, a series of recall votes could result in the KMT losing up to 31 of its 52 seats, giving the ruling Democratic Progressive party a chance to win back control of the assembly.

The recall effort was triggered by a wave of outrage over what the KMT’s critics see as a campaign to undermine Taiwan’s democracy and sovereignty and open the door to China, which claims the island as its territory and has threatened to take it by force if necessary.

The KMT rejects such accusations and decries the recalls as a power grab by the DPP after losing its majority. At a rally this month, KMT chair Eric Chu labelled Lai a “tyrant”, while a campaign video depicts the DPP as “a sore loser who turns over the table when he can’t win”.

But privately, soul-searching has started in the once-dominant party over its failure to win the presidency in three successive elections since 2016.

“In national elections, people’s top priority is avoiding war and maintaining the status quo,” said a senior KMT politician. “Who you trust with that is a very serious question.”

“Advocating cross-[Taiwan] Strait peace has not given us any advantage,” they added. “So we have to conclude they do not trust us with that.”

The KMT controlled the Republic of China (ROC) government on the mainland in the first half of the 20th century, before relocating to Taiwan after losing the Chinese civil war. It then ruled the island under martial law for 38 years.

But in the 1990s, the KMT allowed democratic elections to the legislature and presidency. It also supported amending the constitution to reflect that the ROC government no longer ruled mainland China, which it ceded to the communist People’s Republic.

The KMT also underwent an identity transformation. Its ROC patriotism merged with the Taiwanese identity held by the majority of locals. Chinese nationalists were sidelined and left the party, and native Taiwanese were promoted to its leadership and nominated for office. That helped the KMT stay in power until 2000, and returned it to the presidency in 2008 for another two terms.

Over the past year, the KMT’s legislators have blocked or frozen parts of the budget, including funds earmarked for defence against an increasingly aggressive China. They have also attempted to expand parliament’s powers over the executive, triggering widespread protests.

KMT lawmakers have also proposed draft legislation under which Taipei would abandon its designation of prohibited and restricted waters around islands it controls just off the Chinese coast. The sponsors of the bill say that “the two sides of the strait have not yet legally ended the state of civil war but need to maintain non-violent normal exchanges” and ambiguity would help do so.

The DPP opposes giving up Taiwan’s sovereignty claims, which it argues would help China declare the entire strait its internal waters.

The KMT has blamed Lai for the stand-off with China, and called for the lowering of tensions through dialogue — which Beijing refuses to conduct with the DPP government — as well as economic exchanges and compromise.

KMT officials have made a steady stream of visits to China, where they have echoed Chinese Communist party (CCP) rhetoric that the Taiwanese are Chinese people who want “integration” with the mainland — a fringe position in Taiwan, where a large majority opposes becoming part of China.

Former president Ma Ying-jeou, who ruled out pursuing unification during his two terms in office from 2008, said last month that he supported “peaceful, democratic unification”.

KMT whip Fu Kun-chi has also drawn fire for being wined and dined in Beijing by top Communist party official Wang Huning in April last year but then skipping Lai’s inauguration.

“That’s the behaviour of a collaborator,” billionaire tech entrepreneur-turned-anti-China activist Robert Tsao said this month. “Some people say: ‘What’s wrong with engaging in exchanges?’ But what they are doing is not exchanges, it is collusion.”

Although the KMT publicly rejects this characterisation, several party officials acknowledged that its attitude towards Beijing has shifted markedly over the past decade.

“One reason is that China has become so powerful now,” said a KMT party official. “Look at their military might, their economic clout. They are a global power. How can we not identify with them, how can we not be proud, especially as we are, beyond doubt, Chinese ethnically and culturally ourselves?”

The senior KMT politician said the “peace dividend” of increased business opportunities and personal ties after Ma opened Taiwan to Chinese companies and tourists had created “vested interests”, which some KMT politicians and many of its supporters were reluctant to give up.

“The KMT membership seems to be increasingly out of step with the average Taiwanese citizen in terms of age and ideology,” said Dafydd Fell, a professor at Soas, University of London, who focuses on Taiwan’s politics.

One “key factor”, Fell said, was the “inner party balance of power”. Thirty-one of the KMT’s 195 central committee members come from a party chapter representing military families, a minority whose parents or grandparents fled with the ROC government to Taiwan in 1949. That outnumbers representatives from some counties in the south, where Taiwan-centric identity is strongest. Eight members represent Taiwanese businesses in China.

This constrains the party’s ability to change. The KMT’s China policy is still centred on the “1992 Consensus”, a formula under which it agrees with the CCP that both Taiwan and the mainland belong to one China, but they just disagree over its definition.

Money has played a role, too. Since 2016, a transitional justice committee has frozen a large part of the former Japanese government’s assets, which the KMT appropriated upon its arrival in Taiwan, building a business empire that previously earned it the moniker of “the world’s richest political party”. Depleted of resources, party leaders have struggled to keep members in line.

“That makes them more vulnerable to being bought off by the CCP,” said Kharis Templeman, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution. “When the KMT was the richest party in the world, the CCP promising access to [the] Chinese market wouldn’t have seemed as attractive.”

The disarray has facilitated the rise of more marginal figures. Fu, the caucus whip, previously served more than two years in prison for stock manipulation and insider trading. His power base is in one of Taiwan’s least populated regions. Now one of the party’s most powerful officials, he has played a critical role in the parliamentary obstructionism.

“Things need to change, and we need leadership to do that,” the senior KMT politician said.

That could make the recall vote a blessing in disguise. Sweeping losses could lead Chu to not run again in the election for party chair this autumn and bring to the fore Lu Hsiu-yen, mayor of Taiwan’s second-largest city Taichung, who is seen as the top contender to be the KMT’s presidential candidate in 2028.

“She is pragmatic and has the potential to reshape the party’s image,” said Templeman.

“As the KMT can talk to Beijing . . . they could have a fairly solid argument that they can balance between China and the US better than the DPP can,” Templeman added. “That can be a selling point with voters if they do it right.”