Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

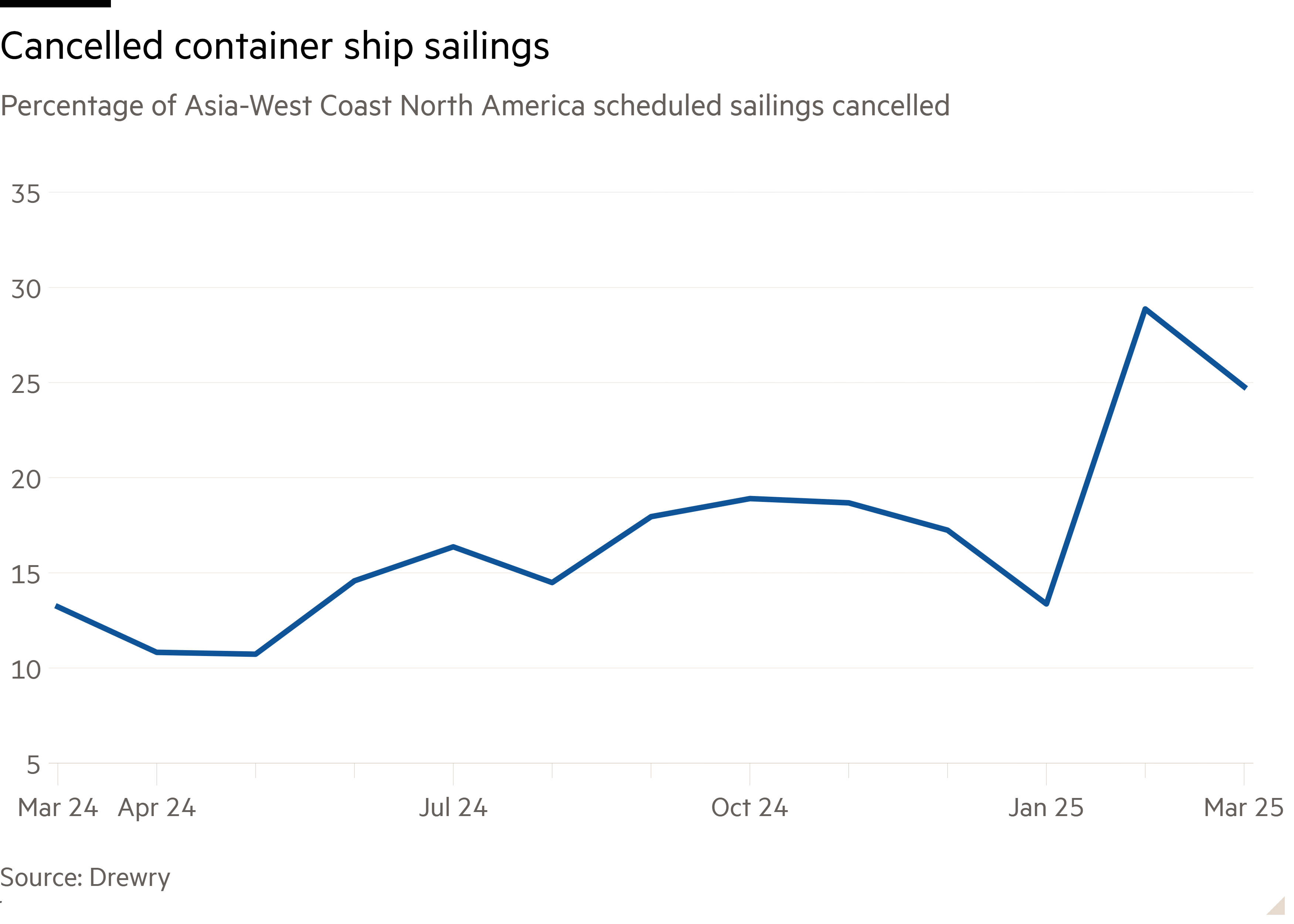

Three years ago the ports on the US west coast, their container terminals and rail lines hopelessly congested by the supposed post-Covid dislocation of value networks, were held to be the locus of a deep and abiding weakness in globalisation. These days it’s the opposite — ports emptying out as Donald Trump’s tariffs punch holes in the sailing schedules of cargo ships from China. Honestly, there’s no pleasing some people.

The first of those actually reflected a rapid post-lockdown recovery of goods through traditional channels rather than anything structurally wrong. Once everyone had bought their first e-bike and stocked their backyards with new garden furniture, the ports (and the economy, more or less) returned to normal. If the US president moderates his tariff war against China, or if value networks find ways of “China-washing” exports to the US via third countries, the same can happen in reverse. Only if Trump is determined to keep ratcheting up protection to stop imports will trade and the economy fail to recover.

In the medium term, it’s going to look pretty nasty no matter what he does. Empty shelves and American children suffering a doll-rationing regime as per Trump’s newfound puritanism will be terrible optics, and small businesses going under because of a shortage of inputs from China might deliver the recession Trump improbably says he’s fine with. Ryan Petersen of the logistics company Flexport, who has emerged as the voice of the freight industry as he did during the post-Covid congestion, says the tariffs are an “asteroid-wiping-out-the-dinosaurs kind of event” for his small business customers.

But the evidence of recent years suggests that both international trade and the US economy are entirely capable of dealing with big shocks without incurring long-lasting damage. Marc Levinson, an economist and historian and author of The Box, the definitive history of the shipping container, says that the shipping industry is in reasonable shape to absorb a China-US shock, even if it leads to a reduction in overall demand rather than just a rejigging of trade routes. Ironically, Levinson points out, the shipping industry’s earnings have been boosted by the Houthis’ blockade of the Red Sea sending container ships round the southern tip of Africa.

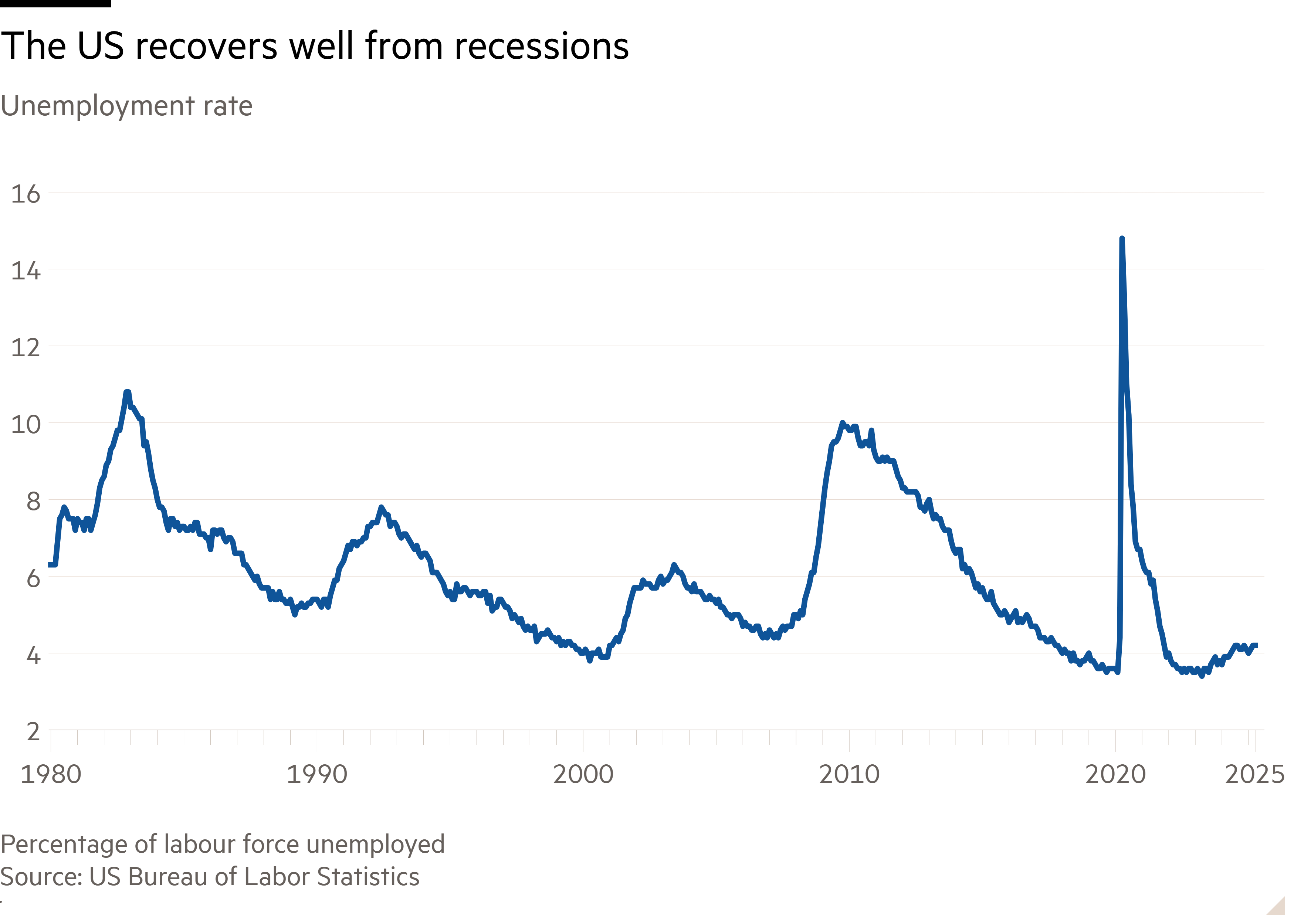

The Covid shock to household confidence and growth caused a world recession in 2020, and global trade in goods and services plunged. But growth recovered smartly with fiscal support and the relaxation of lockdowns. Compared with other advanced economies, particularly in Europe, the US tends to recover from recessions with little “hysteresis” — permanent effects on output and employment arising from cyclical downturns. The US unemployment rate rocketed to nearly 15 per cent in the spring of 2020: it was back below 4 per cent by the end of 2021.

The issue is not so much whether the US and the trading system can absorb the shock of the baseline 10 per cent tariffs Trump has imposed on almost all trading partners so far, and even the much higher tariffs on China. Given time, they probably can. As we saw during his first-term trade war — and as what the IMF calls “connector” economies are gearing up to do now — Chinese exports still make it to the US through some combination of relabelling or a more genuine shifting of value-added production to third countries.

The US is trying hard to clamp down on such circumvention, but it’s a huge market with a massive incentive to find a way round the tariffs. Meanwhile, those value chains with large economies of scale and susceptible to irreversible damage from shocks, notably the car industry, are currently reasonably well protected by carve-outs.

The issue is whether Trump is genuinely determined to block imports from all sources. Given their impact on trade, his tariffs have with some justification been compared to Britain’s decision to leave the EU. The UK government chose a hard form of Brexit that has indefinitely disadvantaged its exporters (and importers) and weakened its long-run productivity, perhaps by 4 per cent — and this where frictions to trade do not dissipate over time. The Trump equivalent would be not simply to impose stable tariffs and let them be, but endlessly to try to plug holes and restrict overall imports in a way that continued to inflict damage, not just to existing trade patterns but to new ones emerging.

Where Trump comes out is anyone’s guess, though it’s increasingly clear that a lot of the US’s big trading partners — China, Japan, the EU — have called Trump’s bluff over his attempt to bounce them quickly into concessions. Since he has a history of backing down in the face of defiance, this is a healthy development. In any case, while American companies exposed to China trade are in for a wrenching adjustment in coming months, it’s only if Trump adopts a “whatever it takes” policy towards restricting any and all imports that serious permanent damage is likely to be done.