Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

How should outsiders want the trade war between the US and China to end? They should want both to lose.

True, Donald Trump’s approach is far worse than intellectually incoherent: it is lethal for any co-operative global order. Some people think a collapse of such “globalism” is even desirable. In my view, it is foolish to imagine that a world run by predatory “great powers” would be superior to the one we have. Yet, while Trump’s protectionism has to lose, Chinese mercantilism must not win, since it, too, creates substantial global difficulties.

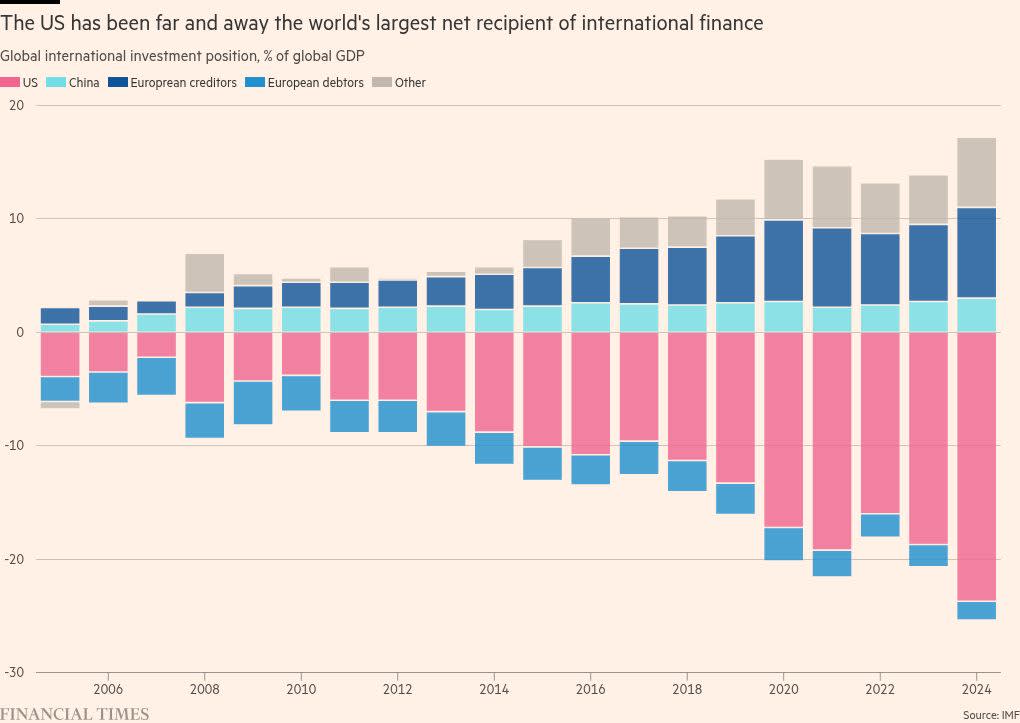

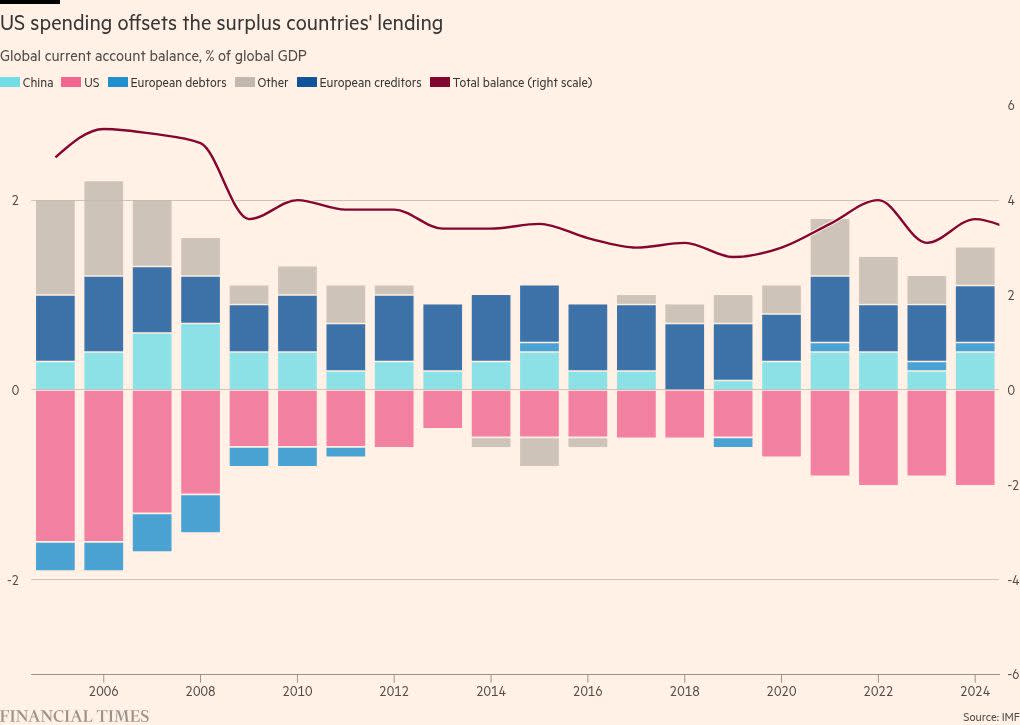

To understand the problems the world economy faces it helps to start from the topic of “global imbalances”, which was much discussed in the run-up to the global and Eurozone financial crises of 2007-2015. In the years since, these imbalances have grown smaller but the overall picture has not changed. As the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook notes: China and European creditor nations (notably Germany) have run persistent surpluses, while the US has run offsetting deficits. As a result, the US net international investment position was minus 24 per cent of global output in 2024. Since the US runs trade and current account deficits and has a comparative advantage in services, it also runs large deficits in manufactures.

So what, a passionate free-marketeer would ask? Indeed, even a not-quite-so-passionate free marketeer might note, with good reason, that the US has been fortunate to live beyond its means for decades. That need not be a problem: nobody, after all, will be able to force the US to pay its liabilities back. It also has ways, both elegant and not so elegant, to default. Inflation, depreciation, financial repression and mass corporate bankruptcies all come to mind.

Yet, one can see at least three large holes in this rather complacent view of large and persistent global imbalances. The first is that they have become politically noxious — so noxious, indeed, that they helped get Trump elected president, twice. The second is that, on the surplus side of the ledger lie negative-sum interventions designed to shift the global balance of economic power. While international relations is not only about economic power, the latter is certainly a crucial part of it.

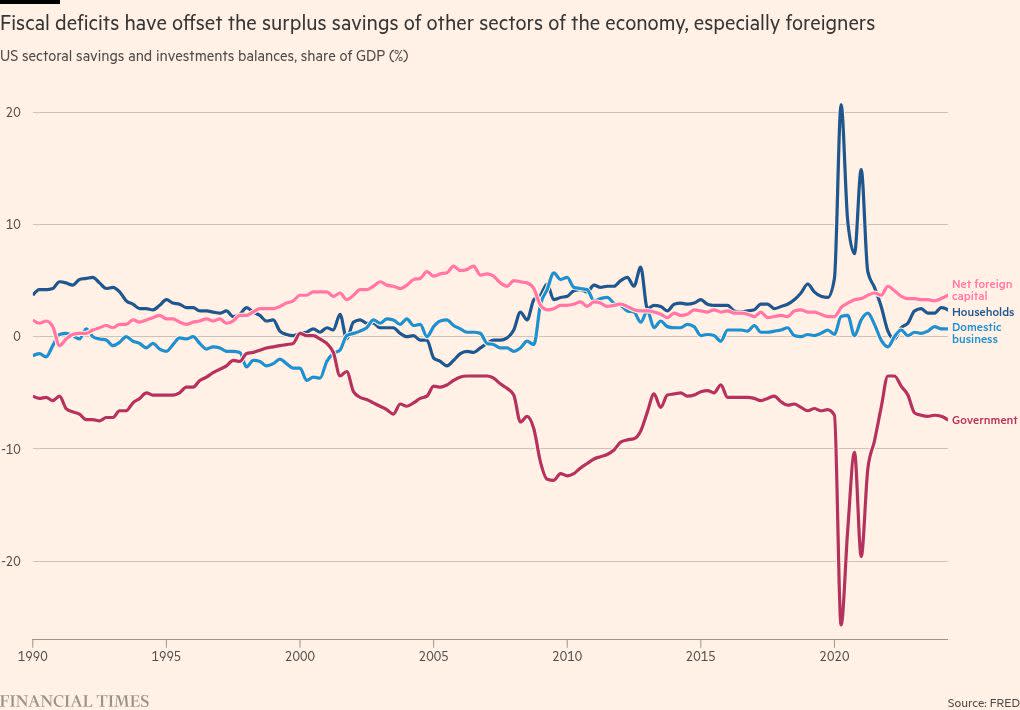

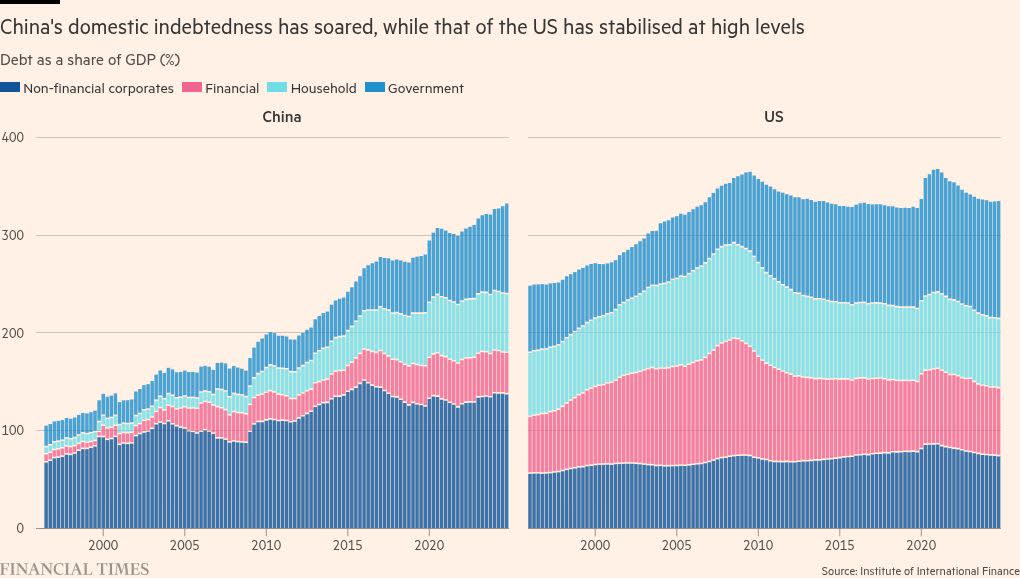

The third is that the counterpart of external deficits tends to be unsustainable domestic borrowing. Combined with financial fragility, the latter can lead to huge financial crises, as it did between 2007 and 2015. Sectoral savings and investment balances are revealing indicators of this last challenge. Foreigners have been running a substantial savings surplus with the US for decades. US businesses have also been in balance or surplus since the early 2000s, while US households have been in surplus since 2008. Since these sectoral balances have to add to zero, the domestic counterpart of US current account deficits has been chronic fiscal deficits.

If real interest rates had been high, fiscal deficits might have been driving the chronic external deficits. But the opposite has been true: real interest rates have been either low or very low. The Keynesian hypothesis looks right: the inflow of net foreign savings, shown in capital account surpluses (and current account deficits) made big fiscal deficits necessary, because domestic demand in the US would otherwise have been chronically inadequate.

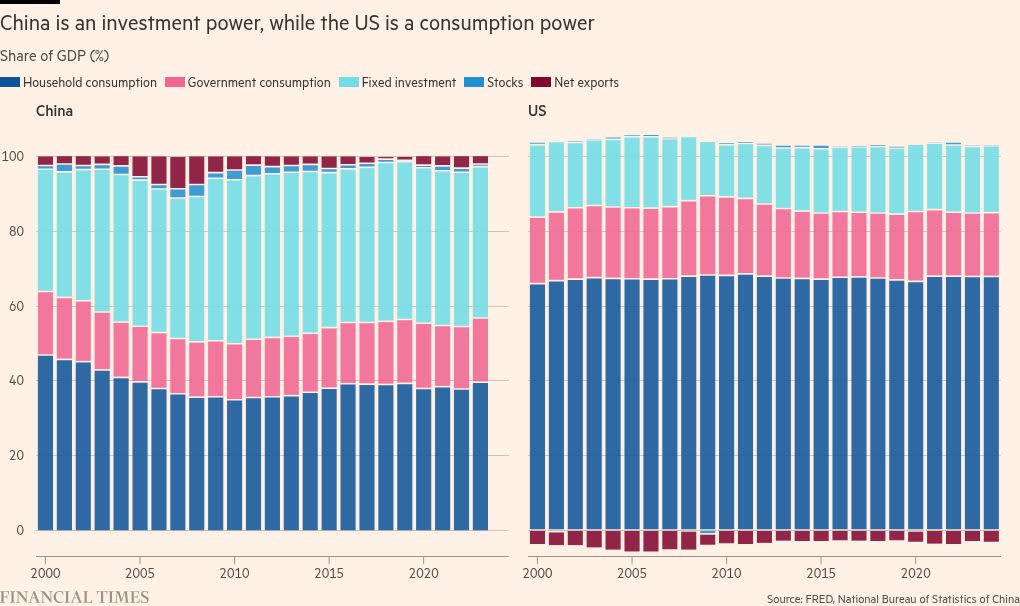

China is not the only player on the other side of the global ledger. But it is the most important. Michael Pettis is, in my view, correct that the world economy cannot easily accommodate a huge economy in which household consumption is 39 per cent of GDP and savings (and so investment) correspondingly huge. What is also clear is that the latter has also helped drive what the Rhodium Group judges a successful Made in China 2025 policy. Inevitably, the existing industrial powers are frightened of this Chinese-made juggernaut.

This brings us back to last week’s question: who will win the trade war between the US and China? I argued that China would do so, partly because the US has made itself so untrustworthy and partly because China has the option of expanding domestic demand and so offsetting lost US demand. Matthew Klein responds, in his excellent Substack The Overshoot, that China has long had this option but has failed to use it. My answer is that China must now do so and thus will indeed choose to expand demand rather than accept a huge domestic slump. We shall see.

The outcome of the US-China trade war and the possible evolution of Trump’s tariffs are the immediate questions. But the broader issues considered must not be ignored. Trade policy should not be judged in isolation. As those who founded the postwar trading system, notably Keynes himself, knew, its success also depends on global macroeconomic adjustment and so on how the international monetary system works.

In the first act of the postwar period, the US ran huge current account surpluses, but recycled them into lending. In the second act, up to 1971, the US surpluses eroded. This led to the end of the dollar peg and generalised floating cum inflation targeting, at least among high-income countries. That system worked well enough before China’s rapid rise. With that, the era during which the US could act as borrower and spender of last resort, tested in the 1980s by Japan and Germany, became politically and economically unworkable.

Trump’s unpredictability and focus for bilateral deals are indeed foolish. But the old US-led economic order is now unsustainable. The US will no longer serve as balancer of last resort. The world — especially China and Europe — has to think afresh.