Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

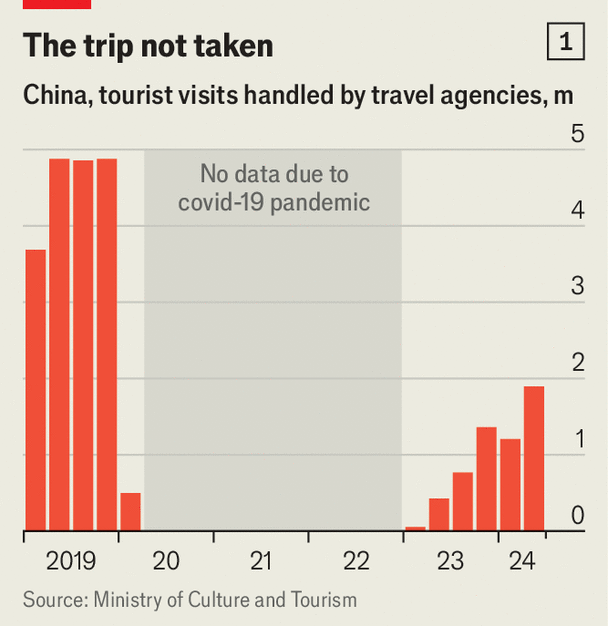

Interesting, safe and easy to get around, China has what it takes to be the top tourist destination in Asia. Indeed, it was. In the first half of 2019, before covid-19 hit, China’s travel agencies handled 8.6m tourist visits, more than any other country in the region, according to the government (see chart 1). China’s border authorities recorded 47.7m entries and exits by foreigners, including non-tourists, over that period. But after plummeting during the pandemic, those numbers have yet to fully recover, coming in at 3.1m and 29.2m, respectively, in the first half of this year.

This matters to China, not only because it enjoyed the bragging rights of being Asia’s top destination. The government is also trying to kick-start the economy—and wants foreign tourists to help. In 2019 their spending accounted for 0.5% of GDP in China, compared with 0.9% in Japan, 1.1% in America and 2.5% in France. In the eyes of Chinese officials, there is plenty of room to grow. But first they must make their country attractive again.

The Economist dug into data from OAG, a consultancy, to figure out which travellers have stopped visiting China. We examined the sales of tickets for flights to and from China, breaking them down by country. The biggest drop-off has been in the number of travellers from America, which declined by two-thirds in the first half of this year, compared with the same period in 2019 (see chart 2). The tallies from South Korea, Japan and Thailand—all big providers of tourists—are also way down.

Flights in the ointment

During the pandemic China closed its borders and put in place draconian restrictions to stem outbreaks. That may have reinforced impressions of the country, held by some travellers, as a brutal and uninviting place. It also led to a decline in the number of flights to China. As of September, monthly seating capacity for flights between America and China was still only 28% of what it was in 2019. America’s big international carriers—American, Delta and United—recently asked the Department of Transportation in Washington for permission to keep most of their routes to China dormant owing to a lack of demand.

Another big problem for airlines is Russia. Traversing its airspace is the quickest way to fly to China from America and Europe. But two years ago America, Canada, Europe and several other places barred Russian airlines from entering their airspace, punishment for Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia responded in kind. That has extended flight times and driven up prices for Western carriers. Take British Airways, which restored flights between London and Beijing in June of last year, after a three-year hiatus because of the pandemic. In August of this year the airline said it would again suspend the route. No reason was given, but reports pointed to the issue of Russian airspace.

The Chinese government is trying to make up for all this by easing entry for some. Over the past year it has begun allowing people from 13 European countries and several others to visit for up to 15 days without a visa. Travellers from dozens of countries can stop in China for up to six days before flying to a third country. These trial programmes are having an effect: in the first half of this year 58% of all visits to China were made without a visa, according to the government.

But officials acknowledge that more needs to be done. A common complaint of tourists is that many vendors do not accept cash or foreign credit cards. In order to purchase most things, visitors must download one of the country’s payment apps, WeChat or Alipay. So the government has released a guide on how to use them. Language is another problem. Outside metropolises like Beijing and Shanghai, few people speak English. And China’s “great firewall” prevents visitors from using services such as Gmail and Facebook without a virtual private network.

The biggest problem, though, may be that negative impressions of China are growing in many places. A survey published last year by the Pew Research Centre in America found that, across 24 countries, a median of 67% of adults expressed unfavourable views of China, compared with 28% who had a favourable opinion. The negative perceptions were largely concentrated in rich countries, or those most likely to send tourists to China. In America, for example, half of respondents named China as the top threat, making it an unlikely holiday destination. ■

Subscribers can sign up to Drum Tower, our new weekly newsletter, to understand what the world makes of China—and what China makes of the world.

The Economist