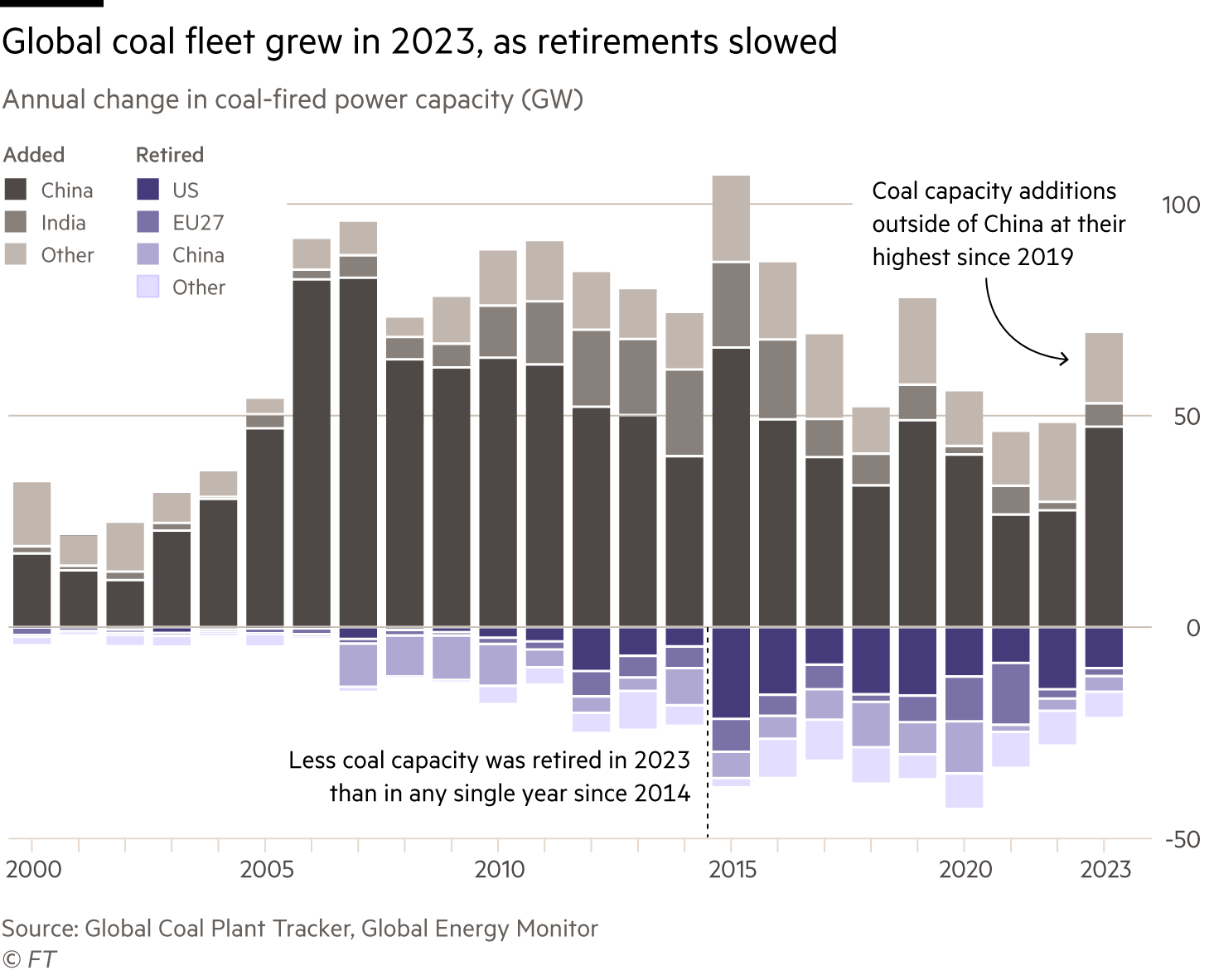

The global coal fleet grew last year for the first time since 2019, mainly driven by new capacity additions in China and a slow down of closures in the EU and the US, the latest data shows.

The new data found that coal capacity increased 2 per cent, according to the non-profit research group Global Energy Monitor, as less coal was retired than in any single year of the past decade.

The increase is expected by the analysts to be short lived, however, as retirement rates are projected to pick up again in the US and Europe over the coming years.

“Coal’s fortunes this year are an anomaly, as all signs point to reversing course from this accelerated expansion”, said Flora Champenois, coal programme director for Global Energy Monitor.

New construction starts outside of China slowed for the second consecutive year with only seven countries breaking ground on new coal projects: Indonesia, India, Vietnam, Japan, Pakistan, Greece and Zimbabwe.

Latin American countries have not had new coal plant construction starts since 2016 and for countries in the OECD, Europe, or the Middle East, no construction has started in the past five years.

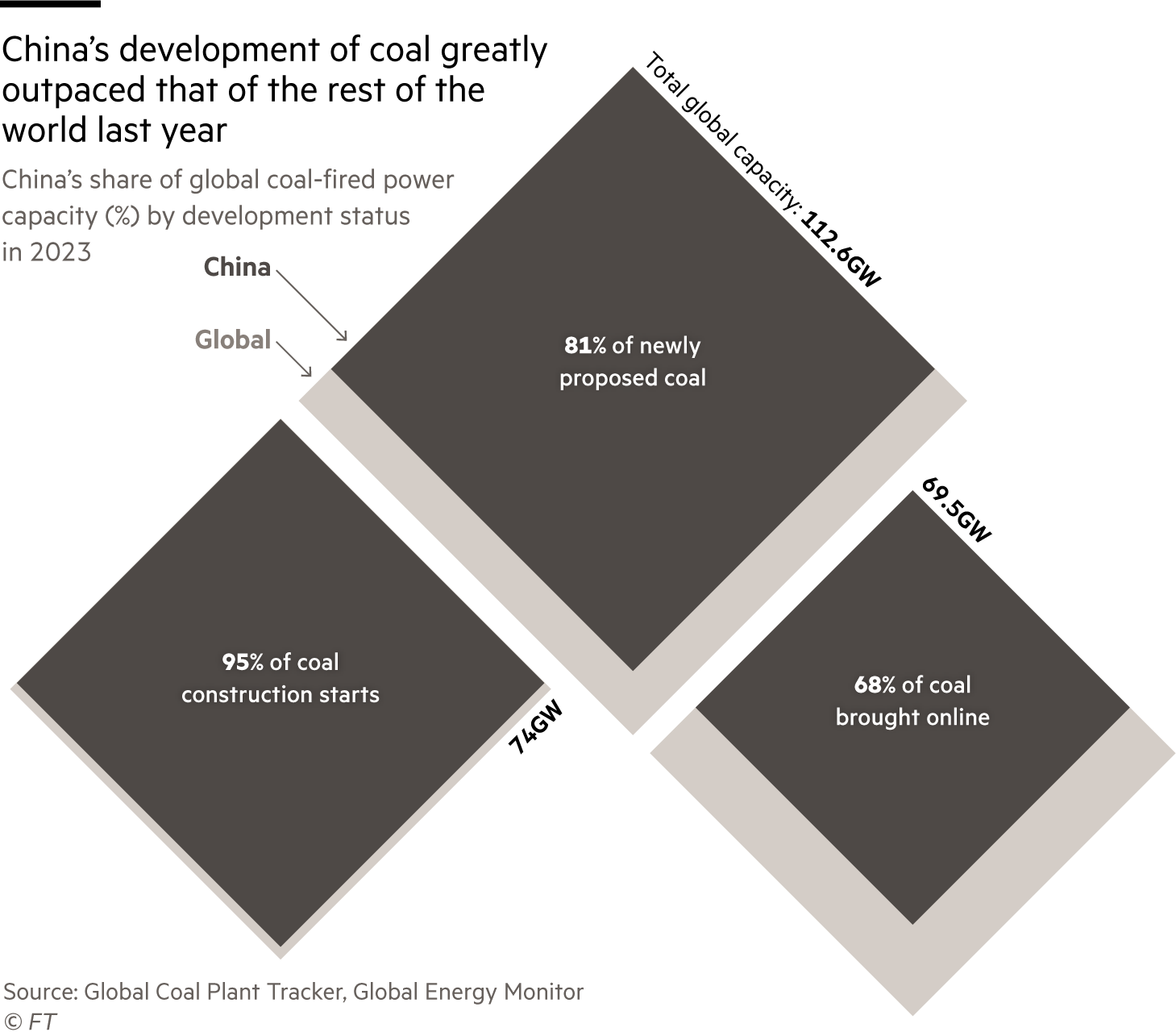

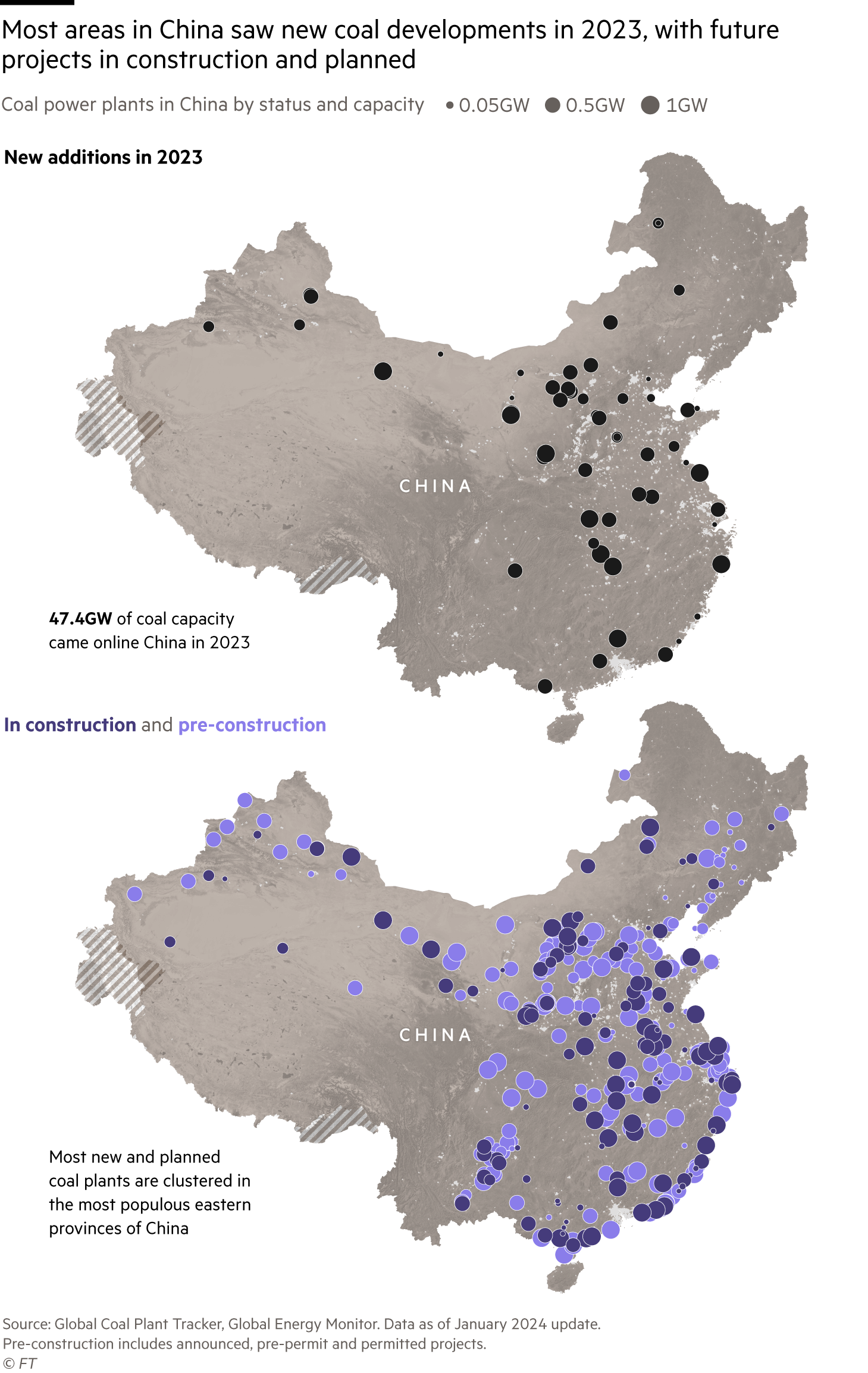

China, however, remained “out of step with the rest of the world”, said Champenois. The energy needs of the biggest economy have outpaced its rollout of renewable energy, which is also the fastest.

But the recent surge in coal power development in China “starkly contrasts with the global trend, putting China’s 2025 climate targets at risk”, said Qi Qin, an analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

In 2021, China’s President Xi Jinping announced stricter controls on new coal project approvals and the country’s national climate pledge was updated to reflect this stance. Yet the capacity additions coming online this year, and the country’s recent spree of permitting and construction, is in tension with its target to retire 30GW of coal capacity by 2025.

In the past two years alone, 218GW of new coal-fired power capacity was permitted with construction of 40 per cent of those plants having started by the end of 2023.

“China is building new coal capacity at record pace, after national officials loosened restrictions on new coal plants due to energy security concerns,” said Anders Hove, senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

“Though the clear signal from national officials is that coal must transition to a supporting role backing up renewables, which are also growing at record pace, the set-up of China’s electricity market still gives grid and local officials incentives to run coal in place of renewables to maximise revenue,” said Hove.

He noted that much of the new capacity was being built in regions where already existing plants would “meet peak load for years to come with coal capacity alone”.

“It’s important to distinguish between how much capacity a country has and how much it uses. China is building enormous amounts of coal capacity, but is also rolling out huge amounts of renewable energy”, said Robin Lamboll, research fellow at the Grantham Institute.

“The blip is still unfortunate, however, as coal is the most polluting of conventional power sources and much less would be needed if China had a better integrated and better balanced electricity grid,” he said.

While China had said its coal use would peak by 2026 and the International Energy Agency had forecast it may be sooner, he said this goal remained uncertain.

The overall rise in global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions of about 1 per cent last year raised expectations that 2024 could be the year that global emissions peaked. Scientists have said the world must cut emissions by 42 per cent between now and 2030 to curb global warming.

As coal is the largest contributor of energy-related emissions, Lamboll said the growth in coal capacity could jeopardise this. “Although the coal usage will likely be far below capacity, more capacity available will likely prolong the plateau in carbon emissions at a time when we should be rapidly declining.”

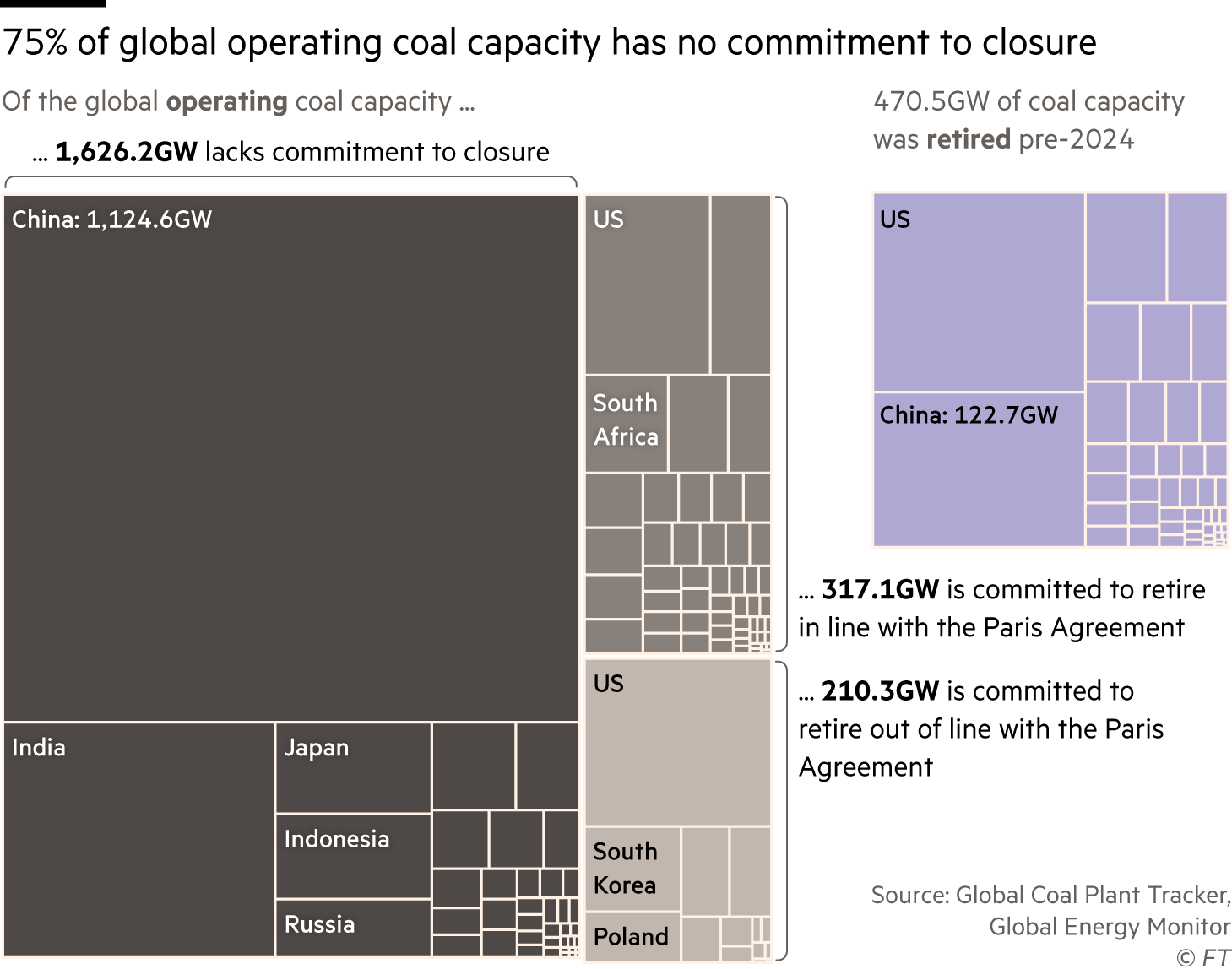

To keep in line with global warming targets under the Paris agreement, the IEA has said that all coal power should be retired within OECD countries by 2030 and the remainder of the world by 2040.

Globally, 470GW of coal-fired power capacity has been retired since 2000. Still, more than four times the coal capacity is operational today than has been retired in the past two decades.

While most online coal capacity is covered by some form of national pledge, only 15 per cent have a detailed commitment to retire that is in line with the Paris agreement.

“The use of coal in energy generation is the single largest threat to keeping the door open to limiting the global temperature increase to 1.5C, in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement,” said Nat Keohane, president at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

“Increasing or even maintaining coal-fired generation capacity is inconsistent with that aim and goes against what has been signed up to at the international level, including just last year at [UN climate summit] COP28.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here