This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. A year after engineering Meta’s share price turnaround, Mark Zuckerberg has sold $428mn in stock, Bloomberg reports. It occurs to us that if he used the money to buy a boatload of VR headsets, it would triple the company’s quarterly metaverse revenue. Give it a think, Mark. Email us your cockamamie schemes: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

New year, same old CRE

On the list of 2023’s overwrought market fears, commercial real estate ranked high. Shortly after Silicon Valley Bank failed, some envisioned a doom loop. Offices faced big demand reductions from remote work, just as rising rates made it more expensive to finance buildings. Regional banks, the main lenders to offices, were already restricting credit. More defaults, more losses for regional banks, tighter credit conditions, repeat.

It didn’t happen. Even as CRE stress rose to a decade high, spillover was contained. The Fed’s generous Bank Term Funding Program insulated regional banks. The magnitude of the problem was smaller than feared. Total distressed US CRE assets, at around $80bn, were less than half the level reached during the great financial crisis, according to MSCI Real Assets. Perhaps most importantly, CRE moves slowly. A diverse asset base with many lenders and long-term lease commitments isn’t going to collapse overnight.

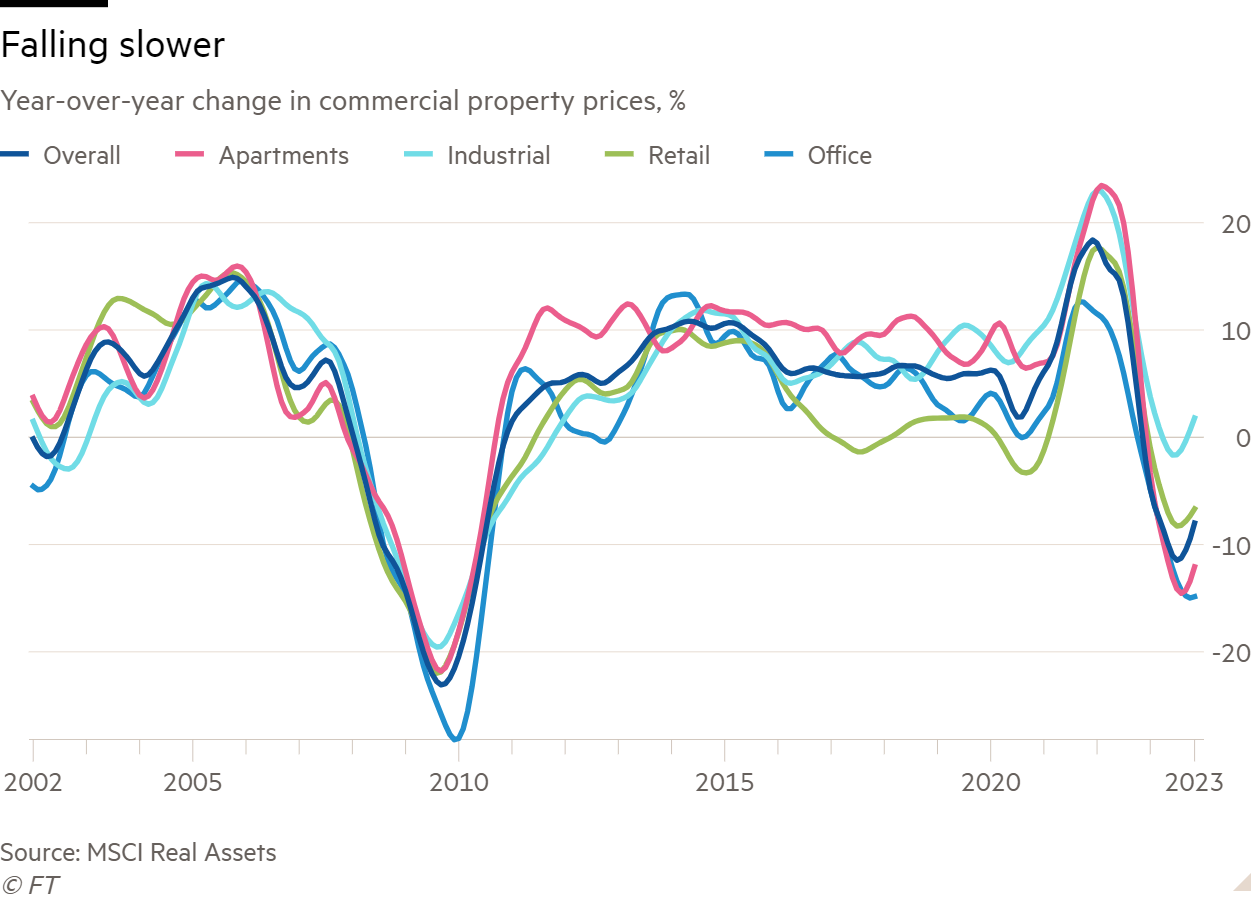

Now falling rates will relieve some of the pressure on CRE. Real estate investors compare rental yields (rental income divided by property value) with Treasury yields. If a property is yielding barely more than a Treasury, it’s not worth the trouble or the risk, so prices must fall to entice buyers. So lower long yields mean property values don’t need to fall as far. And indeed, outside of offices, commercial property price declines are decelerating a little. The office decline may even have stabilised:

Falling rates are a helpful change, no doubt. But the level of rates matters more, and rates remain well above where many buildings were built or financed. The chart below compares actual rental yield spreads with long-term averages. It also includes 2025 forecasts from Kiran Raichura, property economist at Capital Economics, which assume 10-year Treasury yields stay around 4 per cent. The upshot: CRE valuations have further to fall.

The dark blue bars above show actual third-quarter data, when both yields and property prices were higher than today. Fourth-quarter valuations probably look better. But a reasonable conclusion is that the CRE valuation reset still has some ways to go. Raichura suspects we’re about halfway there.

This year will probably bring further pain not only in offices but in multifamily apartment buildings, too. Although offices have so far had the most realised distress, apartments are a bigger asset class and so have the greatest stock of “potential distress”, reckons MSCI.

Unlike offices, which face a broad, long-term shortfall in demand, apartments are dealing with regional gluts in supply. With investors eyeing double-digit rent growth in 2020-21, capital poured into metros like Miami, Austin and Phoenix, leading to huge construction booms. The hangover is here. Some landlords are slashing rents to retain tenants. Rising costs, such as rapidly increasing flood insurance premiums in Miami, also threaten rental yields. And as mortgage rates fall, the single-family home market will become an increasingly viable substitute for renters, piling the pressure on apartment values, notes Thomas LaSalvia, head of CRE economics at Moody’s.

To repeat, this is not a case for systemic alarm, nor investor gloom. Plenty of money will be made snapping up discounted properties. But even if the Fed starts cutting, the CRE slow burn is far from over. (Ethan Wu)

The strange case of Alibaba

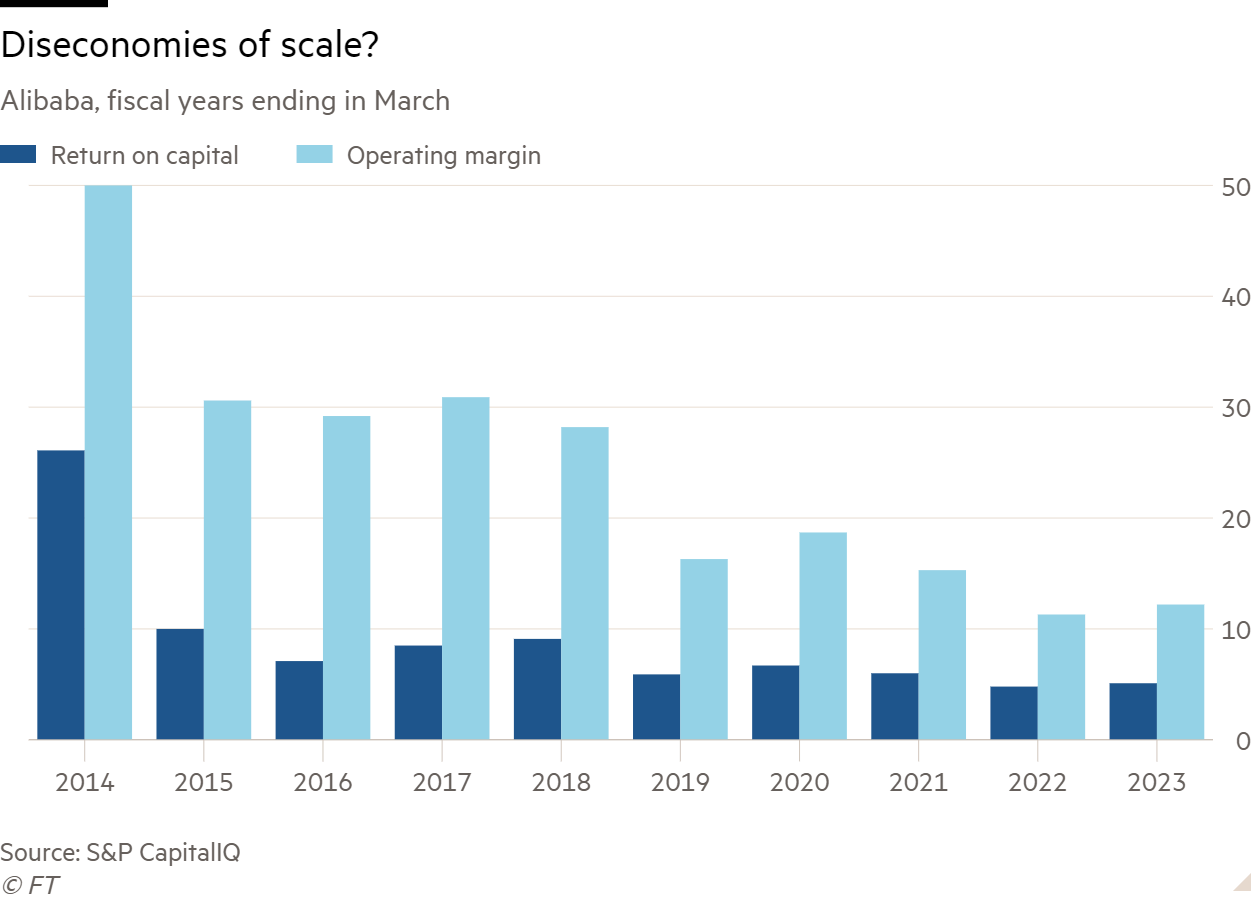

A little less than 10 years ago, when the Chinese ecommerce company Alibaba was about to launch its IPO, my colleague Lucy Colback and I wrote a longish piece about the prospects for the stock. We liked the business a lot. The margins were wide and returns on capital high. It was growing like crazy and had loads of opportunities to expand. We thought the price range for the IPO was attractive.

What we didn’t like was the shareholder structure, in which buyers of the American depositary shares owned a stake in a Caymans corporation that had indirect exposure in the onshore companies that operate Alibaba’s businesses (but did not own many critical assets of those businesses). Owners of the ADS were basically taking it on trust that they would get their share of the value the company created, Lucy and I argued.

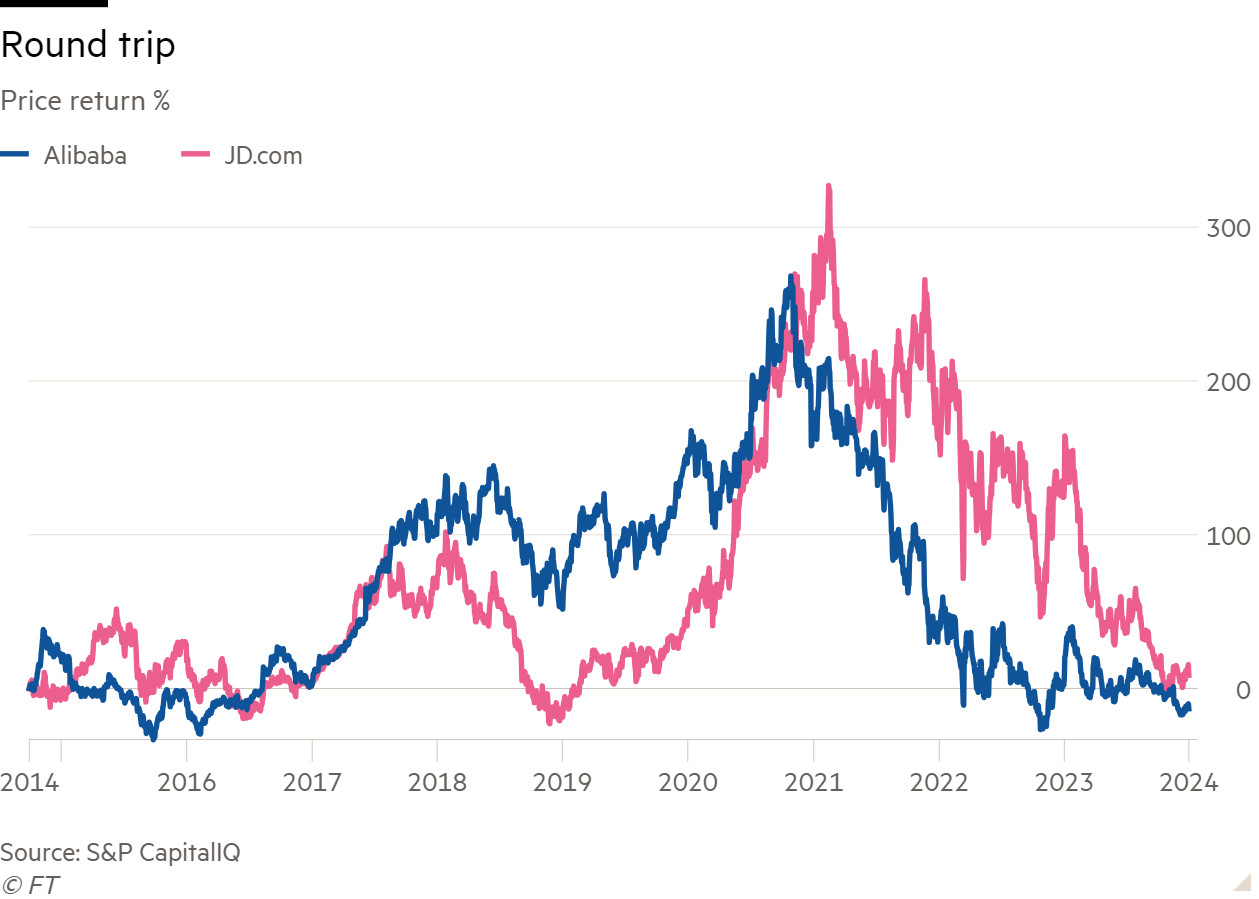

Even having stated those reservations, however, I am surprised by what Alibaba’s stock has done in the intervening decade. Long-term holders are more or less back where they started (I have included Alibaba’s ecommerce rival JD.com in the chart below; the fact that the two track one another is important).

Part of the story can be told in numbers. Here is what has happened to those great margins and returns I admired so much in 2014:

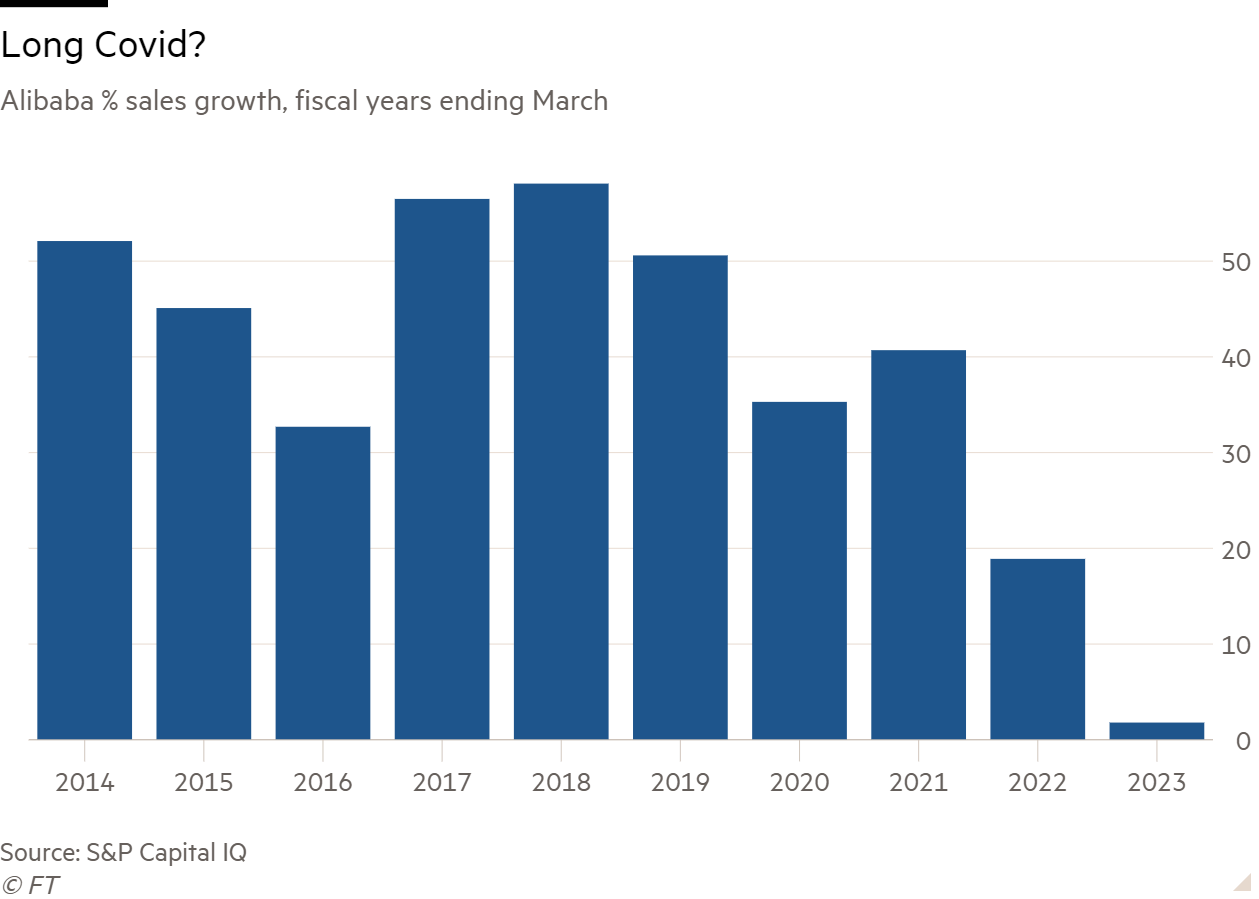

Meanwhile, sales growth has been trending down for several years and collapsed last year.

The narrative behind these numbers is ably told by my colleagues Eleanor Olcott and Cheng Leng in a piece they published on the first of the year. They describe four big, interrelated problems: increasing strategic and organisational sprawl; the core ecommerce business failing to keep pace with competitors such as PDD, Douyin and Shein; a recent collapse in growth in the cloud computing business; and a poorly thought out break-up/reorganisation plan that was largely abandoned shortly after being announced in March.

Chinese stocks are pretty far from the core of Unhedged’s coverage, but Alibaba’s decline into crisis strikes me as important and instructive. For starters, it makes me appreciate what a good job the dominant US tech companies have done (by comparison) of sticking to what they are good at and therefore keeping returns high (Meta seemed poised to fail at this, but corrected course). But more to the point, there are two really big questions I’d like answers to.

First, can this company get itself together? It now trades at about 10 times earnings, down from 30 just a few years ago. If it can demonstrate that it can set priorities and take back share, maybe the stock is way too cheap.

Second, how much of the decline in operational and share performance at Alibaba has to do with the difficult regulatory environment in China? The stories of founder Jack Ma’s run-in with regulators, and of the Chinese Communist party’s wider “techno-authoritarian” crackdown on the tech industry, are well known. The Olcott and Leng piece does not explicitly discuss how meddling by or fear of regulators may have contributed to the strategic problems at Alibaba, but there are plenty of reasons to consider the possibility. The parallel woes of JD.com and its own founder-CEO, Richard Liu, are suggestive. And it is hard not to wonder whether plans for the reorganisation are stuck in some sort of official limbo. For example, Olcott and Cheng note that:

The future of fintech affiliate Ant, in which Alibaba retains a roughly 33 per cent stake, also remains unclear, three years after the authorities halted its $34bn IPO as part of a crackdown on Big Tech. Ant is still awaiting regulatory approval to obtain a financial holding licence, a crucial step to pursue a more modest IPO in Hong Kong or China, according to people close to management.

Similarly suggestive is the fact that Alibaba’s cloud business is struggling in part because one critical competitor is a semi-public entity:

“Alibaba’s cloud growth faces multiple headwinds, including lacklustre private sector enterprise demand, SOEs [state-owned enterprises] increasingly seeking to partner with public-sector cloud service providers like Huawei and . . . ByteDance insourcing its domestic cloud workloads,” said [Bernstein analyst Robin] Zhu.

These suspicions are more or less a restatement of a question we have raised at Unhedged before: does the political context surrounding China’s securities markets demand that assets on those markets trade at a permanent discount?

Readers’ thoughts on Alibaba, the company or the stock, are most welcome.

One good read

No one remembers the pellagra epidemic today, but it was a horror. Also: corn is interesting.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.