Beijing’s Doudian Mosque, with its striking domes and ornate minarets, was one of the grandest mosques in northern China.

But earlier this year, its minarets were removed, its domes replaced with pagoda-style cones and its Arab-style arches squared off.

Mosque demolitions and modifications have been documented in Xinjiang, the northwestern region where hundreds of thousands of Turkic Muslims have been detained, and there has been some evidence of architectural changes elsewhere.

But the Financial Times has now found that Beijing’s crackdown on Islam has spread to almost every region of the country.

A visual investigation based on satellite images of thousands of mosques before and after modification reveals a widespread policy of stripping buildings of Arabic features, and in some cases replacing them with traditional Chinese designs. Some have even been torn down.

An analysis of 2,312 mosques once featuring Islamic architecture shows that three-quarters have been modified or destroyed since 2018.

For some activists, these changes reflect a broader suppression of Islamic culture. “This is the start of the end of Islam in China,” says Ma Ju, a US-based campaigner for Chinese Muslim rights.

Thousands of mosques have been altered or destroyed as Beijing’s suppression of Islamic culture spreads

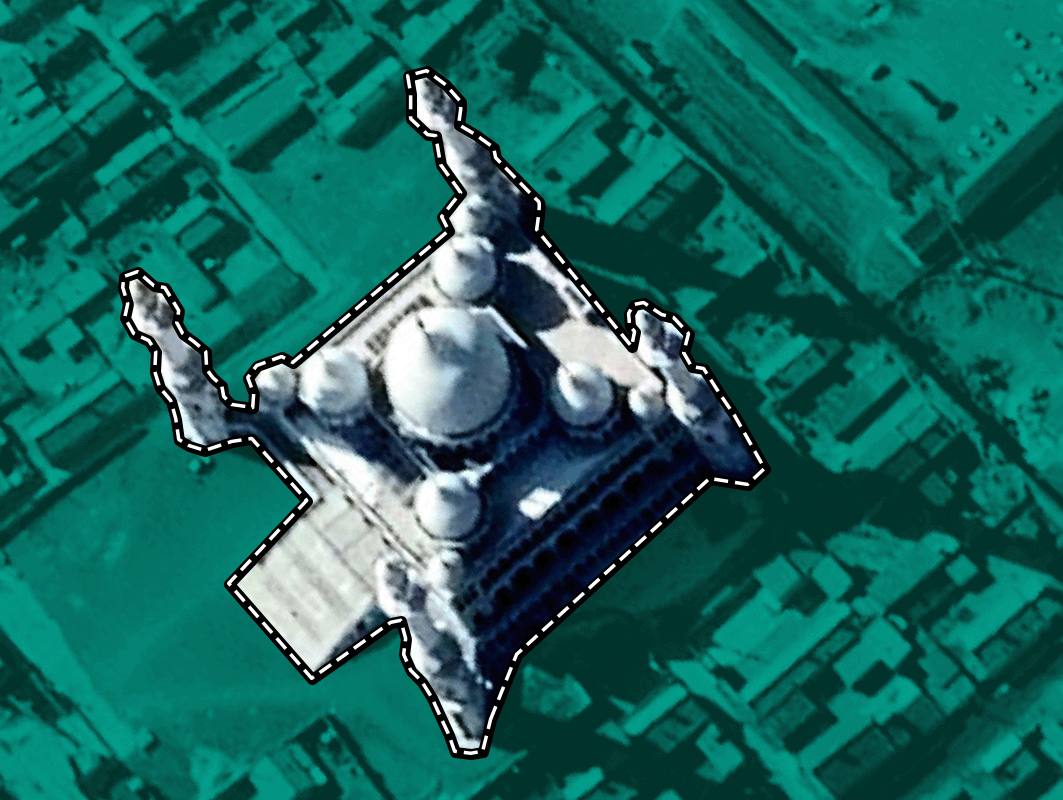

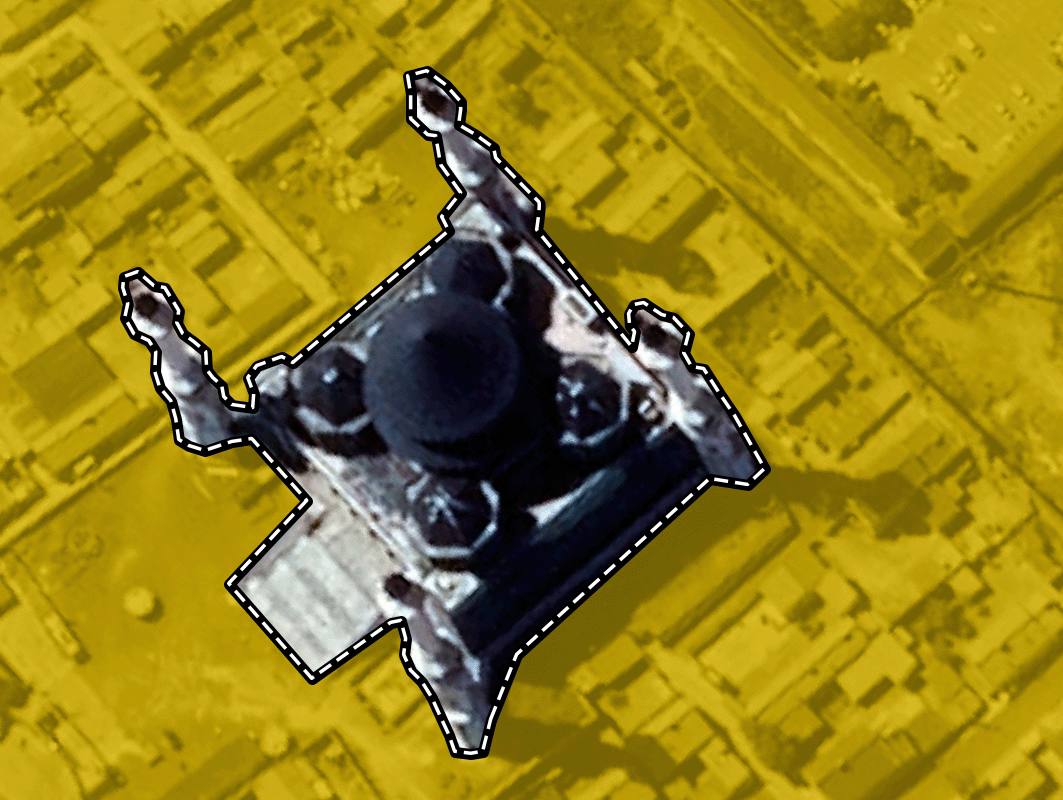

When I saw the demolition [of the mosque dome] begin, I felt pain in my heart,” says Ding, using a pseudonym, when recalling what happened at Najiaying Mosque in China’s south-west province of Yunnan earlier this year. Protests against what officials referred to as the “renovation” of his local mosque were met by riot police in May. “It felt like my home had been forcibly dismantled by someone else and all you can do is watch,” says Ding. “It’s the destruction of our religion.”

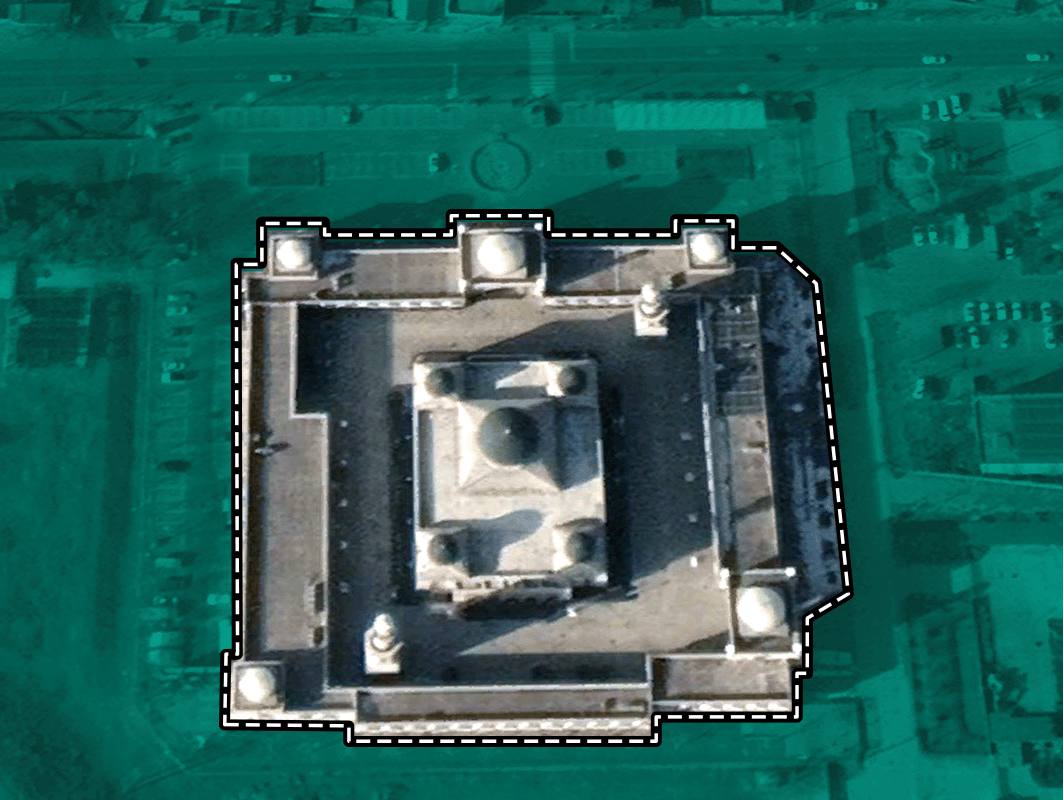

More than 1,000 miles away at the Doudian Mosque on the outskirts of capital Beijing, a visitors’ information display inadvertently shows the dramatic change in the mosque’s appearance: a backlit image of the old building has been loosely covered with a recent photo. As well as having its architectural features removed, most of the Islamic motifs that earlier adorned the mosque’s facade have gone. Its exterior features a number of surveillance cameras.

Doudian Mosque, Beijing

2017

2017 2023

2023In an exhibition off the main courtyard, a large panel urges worshippers to “promote unity” and “oppose division”, quoting both the Koran and traditional Chinese thinkers. Passages of the Koran can still be seen inside the mosque, and the prayer hall is unchanged.

“It does not look completely Chinese, nor foreign”, says a local resident. Instead, it reminds him of the imposing government building that hosts Communist party congresses in the centre of the capital: “It looks a bit like the Great Hall of the People.”

Many locals at the Doudian Mosque, as well as Chinese Muslims approached for interviews, declined to speak or asked to remain anonymous for fear of government reprisal.

What happened to their communities has been repeated across China, with hundreds of mosques modified over the past five years. Satellite imagery shows at least 1,714 buildings have been altered, stripped or destroyed. The government says the changes are to modernise the mosques and “harmonise” them with Chinese culture.

Such modifications have been most prevalent in regions with the highest population of ethnic groups that traditionally practise Islam. In the western region of Ningxia, satellite analysis shows that more than 90 per cent of mosques bearing Islamic architecture have had features removed. In the northwestern province of Gansu, the figure is over 80 per cent.

The FT’s investigation is the first to document the scale and spread of the policy.

A report by New York-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) published earlier this month found a number of altered mosques in the northern regions of Ningxia and Gansu. HRW says that the changes contravene the freedom of religion enshrined in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

A 2020 report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute also documented the destruction and renovation of mosques in Xinjiang, finding two-thirds were changed, mostly since 2017. The FT investigation examined the same mosques and found more had been altered since.

“Respecting and protecting religious freedom is one of the fundamental policies that the Chinese government has upheld over the long term,” said China’s foreign ministry when asked for comment. “[We] take seriously the protection and renovation of mosques and other sites of religious activities, and safeguard the normal religious requirements and activities of worshippers.”

Beyond Xinjiang

China is home to an estimated 20mn Muslims. While the Uyghurs in Xinjiang are probably the best known, more than half belong to the Hui ethnic group — often referred to as “Chinese” Muslims.

James Leibold, an expert on China’s ethnic policies at La Trobe University in Australia, characterises the Hui, in the eyes of the Chinese state, as the “good Muslims”, who “speak the Chinese language, abide by core elements of its culture, and thus can be trusted”.

Hui Muslims live across the span of China, and have been afforded relatively broad religious freedoms, particularly compared with Muslims from Turkic groups, such as the Uyghurs. Chinese authorities have implemented restrictions on Islam in Xinjiang to varying degrees over the past two decades, starting with surveillance and limits on worship. Over time, the Uyghurs have been subject to mass detentions in purpose-built camps, intensive surveillance and restrictions on travel — measures the United Nations says may amount to “crimes against humanity”.

Beijing argues its policies in Xinjiang are necessary to combat terrorism, create unity and foster economic development. The promotion of shared cultural values has also been used to justify the stripping of features deemed non-Chinese from mosques across the rest of the country.

“The taking-down of mosque domes is the most visible aspect of the policy of sinicisation, which is targeting a full-scale rearticulation of the relationship between Party and religion,” says Hannah Theaker, a historian of Islam in China at the UK’s University of Plymouth. She is is building a database tracking the implementation of the sinicisation policy, through which the government attempts to assimilate groups and religions regarded as non-Chinese into what it considers Chinese culture.

Many Hui Muslims fear this means their religious freedoms will now also be eroded. For worshippers such as Ding, the policy is about more than architecture.

“We’ve all deduced that this isn’t just about a dome,” he says. “They want to Han-ify all Muslims, to remove Islam from life . . . To stop prayer, stop religious study. To change our culture, our way of living.”

Najiaying mosque, Yunnan

“The mood is very despondent,” says Ruslan Yusupov, a Cornell University fellow who did fieldwork in Gejiu, Yunnan province, where authorities have started demolishing the dome of the Shadian Grand Mosque — one of the largest mosques in China. “People feel that the government is slowly decreasing the difference between the way it handles Uyghurs and the way it handles [other] Chinese Muslims.”

“But many think it will not come to the camps,” he adds.

Policy shift

For centuries, Hui Muslims have built mosques in a variety of architectural styles, reflecting the period in which they were built. Many mosques and other religious buildings were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. But following the death of Mao Zedong, there was a push for more Arabic-style buildings.

“In the 1980s, during Deng Xiaoping’s liberal era, a new mosque-building boom began, marked by a fashion for domed prayer halls and tall, slender minarets,” says Theaker.

Scholars say the turning point in China’s religious policy came after Xi Jinping became president in 2013. As with almost all national political leaders in the country, Xi comes from the Han Chinese ethnic majority. He has expanded the party’s control over everyday life while also consolidating power to the greatest extent since Mao.

“Xi started to promote Han ethnic nationalism in the name of socialism with Chinese characteristics,” says Haiyun Ma, who researches Islam in China at Frostburg State University. “No Communist party leader before had done such a thing.”

In 2014, Xi placed fresh emphasis on cultural unity in remarks at the Central Ethnic Work Conference. The following year he called for the “sinicisation” of religion in China.

Xi, says Leibold, “views Islamic architecture and symbolism as a threat to the ideological purity and cultural security of its imagined Han Chinese race-state”. “Xi sees it as dangerous because it is Islamic, foreign and anti-Han,” he adds.

Then in 2017, the Islamic Association of China, a government body overseeing the practice of Islam, met to discuss the issue of mosques “copying foreign styles” — officials criticised the “Arabization” of mosques as “competing to squander money” by being “overly large” and “extravagantly decorated”, according to a readout of the seminar. “Mosque architecture needs to be in harmony with our national characteristics,” the meeting emphasised.

Two years later, these remarks were formalised into the government’s “Five-Year Plan on the Sinicisation of Islam”, which set out to standardise Chinese style in everything from Islamic attire to ceremonies and architecture, and called for the “establishment of an Islamic theology with Chinese characteristics”.

“The overall impression of government policy you get is that no Islam will ever be Chinese enough,” says Theaker.

Mohammed, a Hui man from Ningxia, a region in northwestern China, recalls the domes of the mosques around his home village being demolished, despite farmers turning up with shovels to “protect their sanctuary”. Communist party slogans were added to the walls.

“Now, whenever a prayer starts, it’s not the words of Allah in the Koran, it’s a long speech by the imam on how the Communist Party of China is the single legitimate source of power,” he says of services at a mosque near him.

The experiences of Hui Muslim communities have been corroborated by procurement documents from local governments.

Other religions have also been targeted. The government removed crosses from the roofs of over a thousand Christian churches and demolished a vast church — the Golden Lampstand Church in Shanxi province — in 2018. The destruction of Buddhist monasteries in Tibet began before the implementation of the sinicisation policy.

Restricting Islamic life

Beyond the external changes, the government has influenced and restricted the activities of mosques. In 2018, the government-run Islamic Association of China asked mosques to organise patriotic activities, such as raising the national flag, and set up study groups on the constitution, socialist values and traditional Chinese culture.

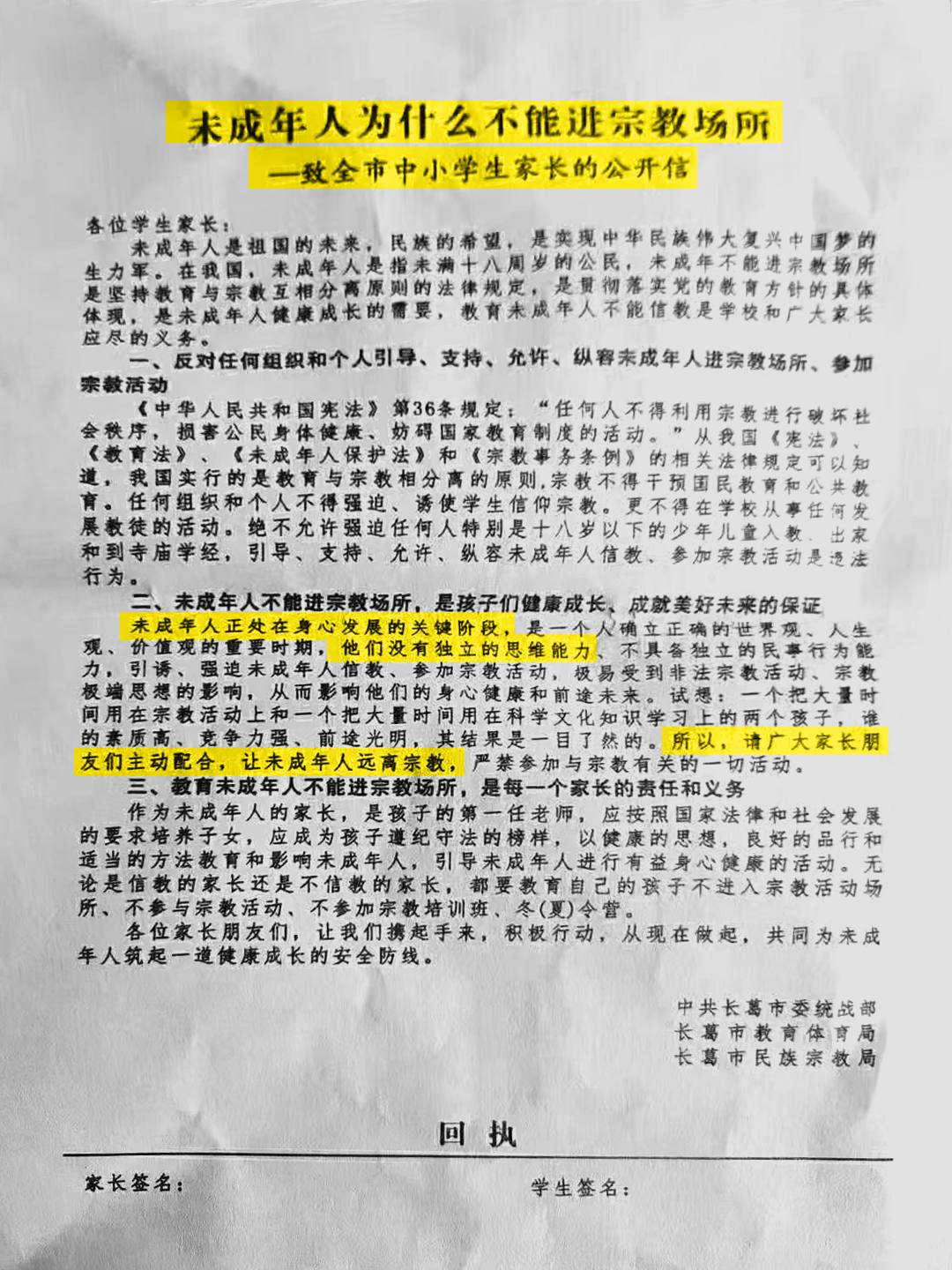

The government has also forbidden online material that advocates religions to minors, with some local authorities circulating notices banning under-18s from entering religious sites, or even practising religion at all.

Why minors cannot enter religious venues

An open letter to parents and guardians of elementary and middle-school students in the entire city

Minors are at a critical stage of physical and mental development…they do not have the ability to think independently… therefore, please could all parents and friends actively cooperate and keep minors far from religion.

In many areas, officials have told current and retired civil servants that their benefits will be taken away if they worship more than a few times per year, according to Hui human rights campaigner Ma Ju.

Mosque-goers say these new policies have reduced the number of people attending prayers. “In the mosque I go to most often, the number of worshippers has reduced by 60 to 70 per cent, because there are people who don’t dare to come anymore,” says a Hui Muslim in Zhengzhou, Henan, going by the pseudonym of Mai.

The reduced attendance is used to justify the policy of “combining mosque congregations” and demolishing buildings, according to historian Theaker. Local government documents show more than a thousand are under threat of consolidation in Ningxia, she says — about a third of all mosques in the province.

Mohammed says he was deeply upset after visiting Weizhou Grand Mosque in Tongxin county, Ningxia, after its modification. “It’s an empty building now, there are locks all over it,” he says. “It’s like the Communist party saying ‘fuck you’ to all Muslims . . . This is the most famous mosque in the whole region, and they can shut it down just like that?”

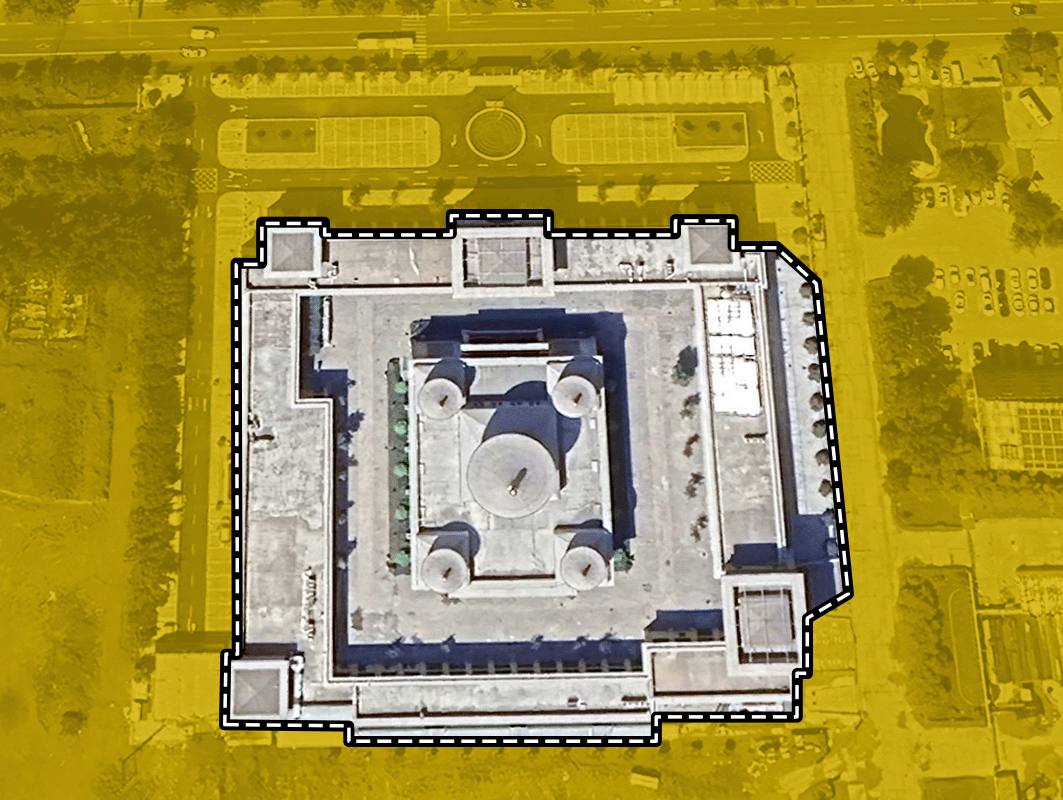

Weizhou Grand Mosque, Ningxia

2019

2019 2023

2023Many other Islamic symbols have been removed from public view. Several Chinese regions have abolished halal certification standards, according to Chinese state media, quoting an official who said that the spread of halal markers on sold goods was the “initial sign of religious extremism”.

Hui resistance

Mai says demolitions in his area began after the former high-ranking Communist Party official Wang Yang inspected religious sites in April 2019.

The golden dome of his local mosque was removed and replaced with a flat roof, as were the golden domes of its minarets. “There was no legal basis for these demolitions,” Mai says. “When we built these mosques, it was with the permission of the government.”

Some Hui Muslims have tried to resist. In 2018, local protests delayed changes at the Weizhou Grand Mosque. The government also postponed renovations to the Xiguan Mosque in Lanzhou city, Gansu. In a possible show of discontent in Xining, the capital city of Qinghai province, a social media account leaked the local government’s plans to “renovate” 19 mosques from 2020 to 2021.

But the authorities have won out. In 2019, remodelling of the Weizhou Grand Mosque finally began, according to Bitter Winter, an online magazine about religious freedoms in China. By November 2023, local authorities in Gansu had removed Xiguan Mosque’s dome and minarets, online photos show.

At Ding’s Najiaying Mosque in Yunnan, hundreds of riot police put down a protest against the demolition of its domed roof earlier this year.

Shortly after the protests, renovations began on another mosque in Yunnan: the Shadian Grand Mosque, one of the largest places of Islamic worship in China. The local government offered to register another mosque in exchange for a quiet remodelling of Shadian Mosque, says Yusupov, the Cornell University fellow.

But Hui Muslims like Mohammed still fear a possible future without Islam in China.

“There is a gradual dying away of religion in the younger generations, and competition between the religious and modern lifestyles,” he says. “They’ve succeeded in suppressing religion.”

To track the spread of the Chinese government’s policy of sinicization, we wanted to identify changes to mosques that had once had minarets, domes, and other external Arabic features. We built a dataset of 4,450 reported locations of mosques across China by combining search results from Baidu Maps, Google Maps, and OpenStreetMap, as well as mosques in Xinjiang from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. We inspected each location using Google Earth satellite imagery, identifying mosques and comparing changes with their architecture over time.

In total, we located 2,312 mosques with Islamic architecture. Of these, 1,714 (74.3 per cent) had Arabic-style features removed between 2018 and 2023. Examples of renovations to mosques small and large were found in every region, and in both rural and urban areas.

The mosques identified are only a sample of the total in China and even this is likely to undercount the total number of modifications. In some areas, the most recent satellite imagery was taken in 2020 and many more mosques have been altered in the years since.

Reporting Team: Peter Andringa, Irene de la Torre Arenas, Max Harlow, Sam Joiner, Lucy Rodgers and Yuan Yang in London, Eva Xiao in New York and Joe Leahy and Sun Yu in Beijing.

Drone footage of the Doudian Mosque by Marine Zambrano.