About 3bn cups of coffee are drunk around the world every day — a number expected to double by 2050 if current trends continue.

But warming temperatures mean up to half of current coffee farmland could soon be unusable.

Climate change is already having a devastating impact on yields.

While fluctuating harvests and unpredictable incomes are forcing farmers to leave the industry.

Whether the world can produce enough beans to fulfil growing demand is in doubt

On the first floor of a busy shopping centre in the middle of Beijing, 26-year-old Xi Xueyang is waiting for his takeaway Starbucks iced Americano.

Xi, a busy start-up worker, picks up what he describes as a quick “utilitarian” coffee from big chains like this several times a week. But he also frequents the Chinese capital’s growing number of boutique coffee shops. “If I find the time and space, I do quite enjoy a good hand-poured coffee,” he says.

Music producer Ji Yuan, 43, is doing just that at the nearby Loose Goose, where drip coffee using single-origin beans costs up to 72 renminbi ($9.90) per cup. “Coffee to me is a beverage that I cannot live without,” he says.

Millions more feel the same, with global thirst for coffee seemingly unquenchable. Consumption has almost doubled over the past three decades and looks likely to continue its upward trajectory. New consumers in China have been joined by others in India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam, as well as growing populations in sub-Saharan Africa.

Long-term growth rates in Asia and Africa — where coffee drinking is often seen as symbolic of entry into the global middle class — are racing ahead of traditional markets in Europe and North America, although from a lower base. Starbucks plans to open a coffee shop in China every nine hours to reach 9,000 locations across the country by 2025, while international coffee brands Costa Coffee, Lavazza and Tim Hortons are also competing to attract the country’s rising number of consumers.

Coffee consumption has almost doubled in three decades

Global coffee consumption, millions of 60kg bags

This all means an ever larger market for beans. If current trends continue, global consumption is expected to double to 6bn cups of coffee every day by 2050. A study by the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment suggests we will need 25 per cent more coffee by 2030.

But whether the industry can fulfil this increasing demand with its current supply chain model is in doubt. The threat from climate change means suitable land for cultivating coffee is declining, growers are struggling to make a living and prices for consumers are rising.

For the past two years, consumption has outstripped production and growers are under threat this year from the return of El Niño, a climate pattern that causes global changes in temperature and rainfall. Robusta prices reached their highest for 15 years in May — blamed on tight supply and El Niño worries.

Consumption of coffee has often outstripped production

Global consumption and production, millions of 60kg bags

The big fear, says Vanusia Nogueira, executive director of the International Coffee Organization (ICO), is that these deficits keep widening and that coffee could become a more expensive, luxury commodity, or perhaps worse, the world’s coffee lovers will be faced with a drink that doesn’t taste as good.

“In an era of accelerated climate change we really have to think differently — think outside the box — and we may not get the coffee that we want,” warns Dr Aaron Davis, head of coffee research at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. “Longer term, I think we’ll be paying more for coffee.”

Coffee’s vulnerability

Although 130 species of coffee have been discovered in the wild, we rely on just two for almost all our coffee consumption: coffea arabica and coffea canephora — commonly referred to as arabica and robusta. The coffee cherries from these small trees make up 56 per cent and 43 per cent of global production respectively, according to the ICO.

The world produces more arabica than robusta

Production by species, millions of 60kg bags

Arabica, favoured by most coffee drinkers, is a sensitive plant particularly vulnerable to warming weather and leaf rust, a fungus that can ruin harvests. The crop’s wild arabica relatives have been placed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List as an endangered species. These wild versions are crucial to the industry as a genetic resource, allowing scientists to cross-breed them with commercial plants to create more resistant crops.

Robusta, meanwhile, is tougher than arabica. It can grow at higher temperatures and is more resistant to pests and diseases. However, it has a less refined flavour and is mainly used for instant coffee. It also remains vulnerable to significant shifts in weather.

The world’s two favourite beans are very different

“Coffee is a tree that loves perfect weather, just like Goldilocks,” says Jennifer “Vern” Long, chief executive of the World Coffee Research institute (WCR), an organisation funded by the global coffee industry and tasked with ensuring its future. “It’s a tree that loves optimal levels of precipitation, but not too much, [temperatures that are] not too cool, but not too hot — just a really optimal zone, which is increasingly hard to find.”

Some estimates suggest that by 2050 up to half of the land used to grow coffee could become unusable. A study by the Institute of Natural Resource Sciences at Zürich University of Applied Sciences found that four of the top five producers of coffee in the world — Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, and Indonesia — would see their best areas for growing coffee decrease in size and suitability. Other countries outside the tropics, such as the US, Argentina, Uruguay and China, could have new opportunities to grow the crop.

Many current coffee-growing areas will become less suitable over time

Suitability change for arabica, 2000-2050

Climate projections are based on Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5, an intermediate scenario.

Source: Grüter et al. (2022) “Expected global suitability of coffee, cashew and avocado due to climate change”

One obvious solution would be to simply shift production to new places. But to do so would be a painful process with significant costs: ecological, such as deforestation, economic and human. Coffee is a highly traded commodity and crucial to multiple economies and millions of lives.

Growers leave industry

The growers at the heart of the industry, with their knowledge and experience handed down over generations, are crucial to the future of coffee. Without ensuring these farmers make a decent living and continue producing across a diverse set of origins, the impact of climate change on coffee supplies and prices will be even more pronounced.

But poverty among growers is widespread. Of the estimated 25mn farmers across 50 “coffee belt” countries, about 80 per cent are smallholder producers working on plots of land of less than five hectares. The majority of production labour is provided by women.

These farmers, already struggling on low incomes, are now often on the front line of the climate crisis and some are seeing their harvests hit by changing weather patterns, bringing droughts, floods and more pests and disease. Many feel they are shouldering much of the climate burden for little or no reward and are deciding to leave the industry.

“Farmers don’t see a future in coffee,” says Eleanor Deans, sustainable sourcing manager at Fairtrade. “If no one wants to grow anymore, how are we going to drink any coffee?”

Organic farmer Silvia Gonzalez, who cultivates two varieties of arabica in northern Nicaragua, says some growers in her network have seen yields decline from more than 2,000kg down to 1,500kg per manzana — a unit equating to just under a hectare.

Gonzalez, who serves on the board of directors for the Latin American and Caribbean Network of Fair Trade Small Producers and Workers, blames changing weather patterns, which have brought drought in the rainy season and rain in the dry season.

“This has caused a proliferation of pests, which have had a [negative] influence on the quality of the coffee.”

Most growers are unable to confront the climate crisis head on because of their precarious place in the value chain.

Producing countries retain less than 10 per cent of the retail value of the estimated $200bn annual coffee industry, while big companies based in higher-income, importing countries keep most, according to the World Intellectual Property Organization, a UN agency.

Daniele Giovannucci, founder of the Committee on Sustainability Assessment and co-author of the World Intellectual Property Organization’s report, says producers are not rewarded for the climate risk they are bearing.

“If I had to throw a number at it, I’d say 75 per cent of the risk embedded in the coffee industry from crop to cup occurs among farming communities. And they certainly do not earn anywhere close to a commensurate amount for the risk,” says Giovannucci, who once tried and failed to persuade a former Starbucks chief executive to add three cents to a cup of coffee to double farmer income.

Sustainability experts argue a fundamental rethink of how coffee is priced is needed to ensure its future. Otherwise, farmers will not have the financial resources to build climate-resilient businesses and consumers know they’re buying a sustainable product.

Key to this reset is a greater focus on culture, history and farm stories, much like in the cheese and wine industry, Giovannucci says. He points to Parmigiana, Stilton and Champagne — products that are geographically specific and command good prices.

“The question for us is, I think, whether the industry will be smart enough to create the narratives we’re talking about — of amplifying the intangibles of an origin, of a human and ecological story,” he says.

Power of science

Organisations connected to the coffee industry are now rallying to try and save its long-term future.

The WCR argues an injection of cash into agriculture research and development could tackle the impact of climate change as well as ensure coffee producers make a decent living. An extra $452mn a year over the next decade is needed to ensure farmers have the plant varieties and innovations needed, the non-profit concluded in research released this June.

The cash, ideally from a mix of public and private investment, could help fund research into more resilient plants, better disease and pest control, new ways of protecting water and natural resources and enhancing soil health, as well as best practice in farm management.

Where the investment would go would depend on who was funding it. But it is consuming countries that need to “lean in” to co-finance this R&D agenda alongside low-income, producing nations after decades of underinvestment, says Long of the WCR.

“Then we could actually create the kind of innovation required to meet all of our consumer demands around greenhouse gases, reduce pesticide use, drive up productivity, which gives farmers a pay rise, and really enable many countries to successfully export coffee. It’s doable.”

Alongside agricultural R&D, improved access to marketing expertise and the use of technology, such as using DNA fingerprinting to identify varieties that can then be promoted to roasters, could all help drive up productivity and prices. Further support for these measures, in addition to access to finance and credit mechanisms, will help bridge the gap between production and consumption, Long says.

Most of the increase in production over the past decade has come from just three countries — Brazil, Vietnam and Colombia — which have all invested in farm technology and climate-resistant plants.

“As a scientist, I’m an eternal optimist,” says Long. “I think we can innovate our way out of this mess.”

South America and Asia & Pacific are the biggest producers of coffee

Global production, millions of 60kg bags

South America dominates arabica — driven by Brazil and Colombia . . .

Arabica production, millions of 60kg bags

. . . while the Asia and Pacific region leads the pack in robusta

Robusta production, millions of 60kg bags

The ICO has also established a task force, made up of about 40 stakeholders, spanning big brands and governments. Its road map aims to guarantee an economically, socially and environmentally sustainable coffee supply by 2030.

Climate change is “coming faster” than the industry thought, admits the ICO’s Nogueira, and innovators are trying to find short-term solutions “in a culture that is not used to the short term”. “I can’t say I am not worried, but we have many people in the industry, many researchers in the world who are looking for solutions.”

The big coffee companies, however, have been accused by growers and sustainability experts of not doing enough to help.

Michelle Burns, head of global coffee, social impact and sustainability at Starbucks, says the company is “committed to sourcing coffee responsibly, for the betterment of people and planet” and is “actively working to ensure” the future of coffee at the company’s own research coffee farm in Costa Rica.

The company has invested more than $150mn in communities to encourage innovation, will donate 100mn climate-resilient coffee trees to Central America by 2025 and has co-created the Sustainable Coffee Challenge with Conservation International to find other solutions, she says. The company also pays farmers above the market price, she adds.

A new bean?

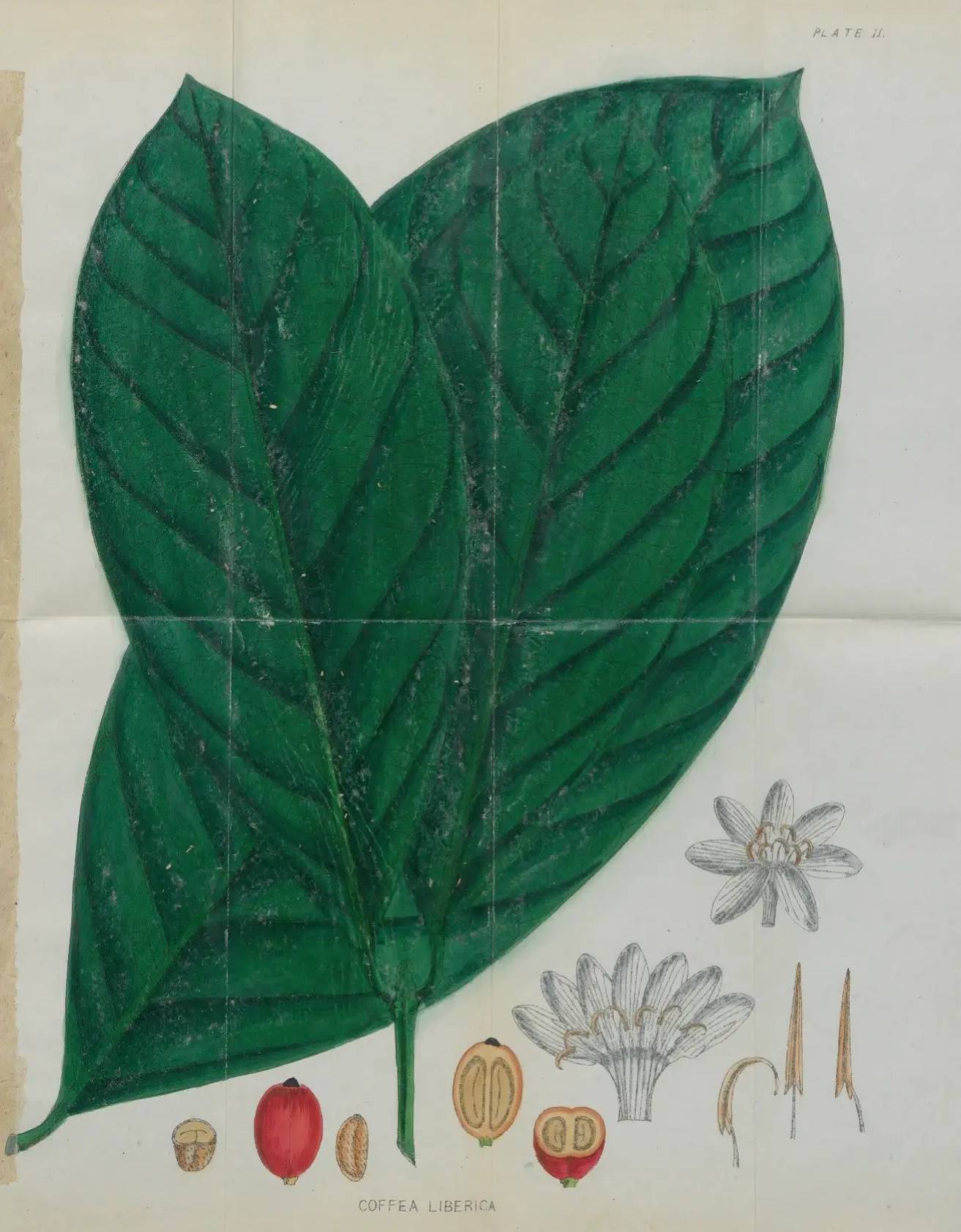

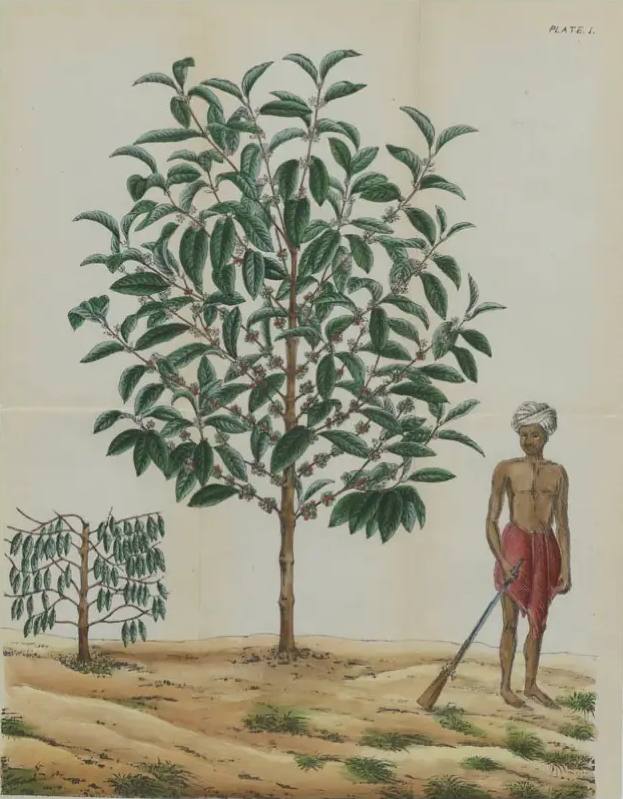

A longer-term, radical solution, put forward by scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is to broaden the “global crop portfolio”, introducing another bean. A variant of coffea liberica — popular in the 19th century but dismissed for its unpleasant flavour — is showing promise, say researchers.

Liberica rose to prominence in the late 1870s but its flavour profile did not catch on © Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Alongside renewed interest in the traditional, larger-seeded liberica, an increasing numbers of farmers in Uganda and South Sudan have begun turning to a smaller-seeded variant of the species, known as excelsa. While they previously mixed it into lower-priced robusta, they are now beginning to sell it under its own name.

With a taste closer to arabica but thriving under warmer conditions at lower elevations like robusta, excelsa shows promise, says Kew Gardens’ Davis. He suggests it could be bred with arabica or robusta to create more climate-resilient plants or even become a commercially viable product in its own right. Coffee traders are already planning to ship the bean, described in Kew research as having tasting notes of “cocoa nibs, peanut butter, dried fruits, demerara sugar and maple syrup”, to speciality roasters.

“I think the key thing for us is it has the potential to be mainstreamed,” says Davis. “This is not something that’s niche.”

The ICO’s Nogueira, who grew up on a small coffee farm in Brazil, is open to the idea. “In some years, maybe we will be talking about arabica, robusta, liberica and others in the same way.”

What is clear to almost everyone involved with coffee, though, is that something has to change, and quickly, if future demand is to be met.

Vivek Verma, chief executive of the coffee side of the Ofi trading company, says consumers now consider coffee “more of a necessity than a luxury” and that new blends may well have to be introduced to serve them. But the industry still needs to make it economically viable for producers to keep their farms going to do so, he adds.

“Otherwise we risk losing some of the rich diversity of flavours from multiple origins that gives coffee its widespread charm and appeal.”

Animations and illustrations by Cecilia Reeve. Cecilia is a painter and animator based in London. She works in gouache paint and hand-drawn, traditional animation. She recently completed an MA in animation at the Royal College of Art.

Additional development by Emma Lewis.