Receive free Climate change updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Climate change news every morning.

The writer is director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard University Kennedy School of Government

At the foot of the Eqi Glacier in Greenland in June, I watched ice formed thousands of years ago drop into the warming ocean. With this vivid depiction of climate change in my mind, I was disappointed that neither of the conferences held last month to prepare for the UN’s upcoming COP28 summit had produced any real breakthroughs.

However, while the need for climate action is rising, the stakes for COP, perhaps counter-intuitively, look to be diminishing. An underwhelming COP28 would be a missed opportunity but it may not be a tragedy. Twenty or even 10 years ago, it was reasonable to hope a co-operative approach could address climate. But it is no longer a realistic expectation — nor the most promising route for progress.

For a generation, the co-operative approach embodied in the COP made sense. As carbon emissions transcend borders, the best strategy was a co-operative one; no one country can address the challenge alone. For most of the past 30 years, that logic was consistent with the dominant international dynamic. While there were disagreements, there was an absence of great power rivalry.

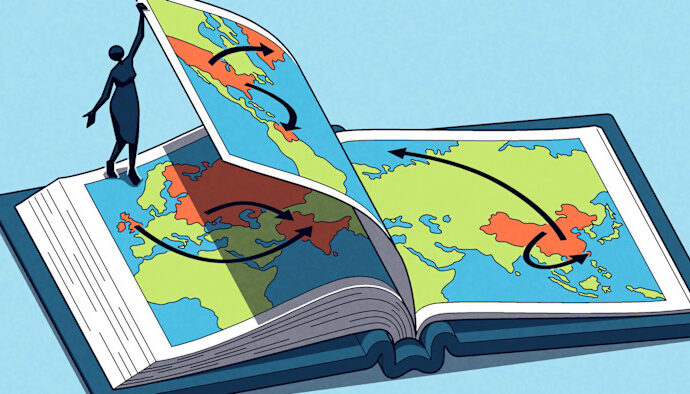

Today, we are in a different world. Collaborative undercurrents of the past have been replaced by great power competition that has permeated across the globe. US-China tensions pull at countries from south-east Asia to Latin America. The effects of Russia’s war in Ukraine have been crippling for people living thousands of miles from Europe. The dominant dynamic is one of competition, and even conflict.

The Biden administration and other governments have hoped that climate can be an exception to this new power play — an island of co-operation between the US and China in an otherwise hostile sea. Yet, although Washington and Beijing share deep common interests in addressing climate change, these interests have not led to meaningful co-operation on action and are unlikely to do so as their relationship deteriorates further.

It is therefore not just folly, but also irresponsible, to expect that a co-operative mechanism like COP will be the primary means to deliver climate action in an era of global competition.

Without question, governments, business and civil society should make the most of the opportunities that COP and other such venues present. However, governments should think more strategically about how they can harness the competitive dynamic characterising global politics today to achieve climate goals, rather than hoping for a respite from it.

Already, elements of a competitive approach to tackling climate change are emerging. The US Inflation Reduction Act was spurred in equal parts by the desire to address climate and the imperative to enhance American competitiveness in the face of Chinese challenges. Similarly, the revival of industrial policy around the world reveals not only the recognition that policy is required, alongside markets, to expedite the energy transition, but also the need to enhance domestic industries and curb foreign dependencies.

The challenge for policymakers is to further map out a competitive approach for climate action.

A good next step is to consider climate finance. Although there is not yet agreement on how to tackle the issue at COP28, good work is being done on how to reform the global financial system to expedite the flow of capital to developing countries caught in the crosshairs of the energy transition.

Perhaps a more competitive approach will yield further — or complementary — results. The IRA has transformed how the US aims to tackle climate change domestically but allocates no resources for a different policy internationally. Washington and the governments of other developed countries have the opportunity and the imperative to remedy this.

Building deep connections between their economies and those of the developing world through climate-related investments will have geopolitical advantages in an era of great power competition.

Appreciation of this should lead to more concessional lending to the global south for climate reasons — which should expand the number of plausible investments, and spur a significant uptick in climate-related projects in the developing world.

Instigating a race between the US, China, and other actors like the Gulf States — and their private sectors — to meet climate financing needs of countries in Africa, south-east Asia, Latin America and elsewhere is what will catapult us to a new level of climate action — with or without a successful COP in November.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here