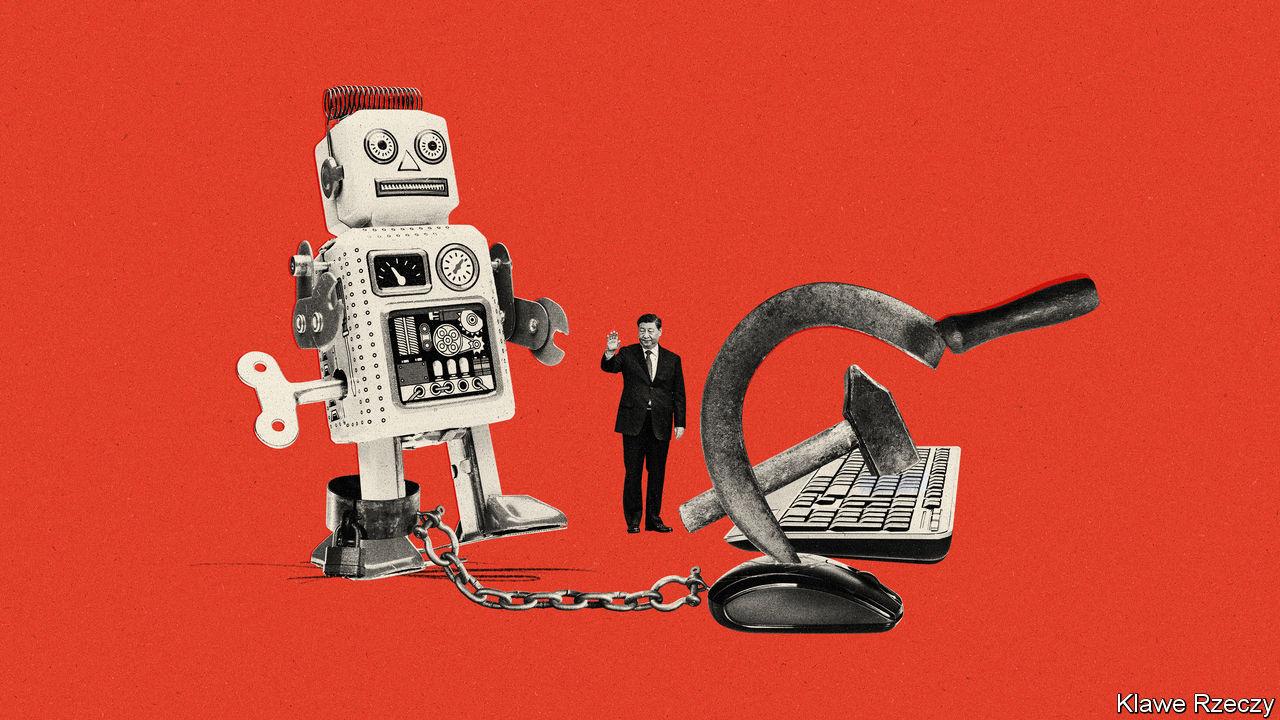

IN THE PAST month or so, China’s tech giants have been showing off. Baidu, Huawei, SenseTime and Alibaba have all flaunted their artificial-intelligence (AI) models, which can power products and applications such as image generators, voice assistants and search engines. Some have introduced AI-powered chatbots similar to ChatGPT, the human-like conversationalist developed in America that has dazzled users. The new offerings have names like Ernie Bot (Baidu), SenseChat (SenseTime) and Tongyi Qianwen (Alibaba). The latter roughly translates as “truth from a thousand questions”. But in China the Communist Party defines the truth.

AI poses a challenge for China’s rulers. The “generative” sort, which processes inputs of text, image, audio or video to create new outputs of the same, holds great promise. Chinese tech firms, hit hard in recent years by a regulatory crackdown and the pandemic, see generative AI as creating vast new revenue streams, similar to the opportunities brought by the advent of the internet or the smartphone.

The party, though, sees generative AI as opening up vast new ways for information to spread outside its control. Its leaders may draw different comparisons than do tech executives with the internet, which once seemed destined to help democratise China by increasing access to unfiltered news and easy communication tools. “Nailing jello to a wall” was how, in 2000, Bill Clinton described the party’s attempts to control the web. Yet, by deploying an army of censors and digital barricades, the party has largely succeeded in creating an internet that serves its own purposes and cultivated an industry around it. Might something similar happen with AI?

New jello, new nails

Rules proposed by China’s top internet regulator on April 11th make clear the government’s concerns. According to the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), firms should submit a security assessment to the state before using generative AI products to provide services to the public. Companies would be responsible for the content such tools generate. That content, according to the rules, must not subvert state power, incite secession, harm national unity or disturb the economic or social order. And it must be in line with the country’s core socialist values. Those restrictions may sound arcane, but similar rules, applied to the internet, let the party repress speech about everything from Tibetan and Uyghur rights to democracy, feminism or gay literature.

China’s proposals come as governments around the world wrestle with how to regulate AI. Some, such as America’s and Britain’s, favour a light touch, relying on existing laws to police the technology. Others seem to think that new regulatory regimes are needed. The European Union has proposed a law that categorises different uses of AI and applies increasingly stringent requirements according to the degree of risk. China’s approach appears more piecemeal and reactionary. Last year, for example, the party feared that “deepfake” images and videos might disrupt the tightly controlled information environment, so it issued rules on such technology that are like the new regulations. One clause banned AI-generated media without watermarks or other clear labels of origin.

There are other similarities to China’s approach to the internet. Its web controls, often referred to as the “great firewall”, may seem monolithic. But keeping out “harmful” foreign content is only part of a more layered effort, developed over time and involving many different agencies and companies. The first stage was all about laying the groundwork for an internet the party could control, says Matt Sheehan of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think-tank in Washington. Today the Chinese government is again building up its bureaucratic muscles and adding to its regulatory toolkit, this time with generative AI in mind. Mandating security reviews and requiring firms to register their algorithms with the state are examples of this, says Mr Sheehan.

China’s control of the internet has not stifled innovation: just look at firms like ByteDance, the Chinese parent of TikTok, a much-adored short-video app. But when it comes to generative AI, it is difficult to see how a Chinese company could create something as wide-ranging and human-like (which is to say, unpredictable) as ChatGPT, while staying within the government’s rules.

The CAC says that the information generated by such tools must be “true and accurate” and the data used to train them must be “objective”. The party has its own definitions of these words. But even the most advanced AI tools based on large-language models will occasionally spout things that are actually untrue. For a product like ChatGPT, which is fed on hundreds of gigabytes of data drawn from all over the internet, it is hardly feasible to sort through inputs for their objectivity. Strict enforcement of China’s rules would all but halt development of generative AI in China.

For this reason, experts doubt that the measures will be tightly enforced. Within the draft regulations there is scope for moderation. When generated content falls outside the rules, the government calls for “filtering and other such measures” and “optimisation training within three months”. That sounds similar to the tweaking of models carried out by Western firms to, say, stop their chatbots from spewing homophobic content or providing instructions on how to make a bomb. Local AI regulations introduced by the city of Shanghai are even looser, stipulating that minor rule-breaking might not be punished at all.

The arbitrary nature of the CAC’s proposed rules means that it can tighten or loosen as it sees fit. Such flexibility in other countries might be seen as a good thing. But as big internet firms can attest, the Chinese government has a habit of rewriting and selectively enforcing rules based on the whims of President Xi Jinping. In recent years companies in fields such as e-commerce, social media and video-gaming have had to rethink their business models. In 2021, for example, state media declared video games to be “spiritual opium” and regulators told gaming companies to stop focusing on the bottom line and instead work on reducing kids’ addiction to playing. If Mr Xi does not like where generative AI is going, he has the power to reset that industry, too.

One way Chinese AI firms might be held back is by limiting the personal data made available to train their AI models. The party runs the world’s most sophisticated surveillance state, collecting masses of information on its citizens. Until recently, China’s tech companies were also able to hoover up personal data, the lifeblood of many businesses online. But this freewheeling era seems to be coming to an end (for the private sector). Now companies wanting to use certain types of personal data must, in theory, obtain consent. Last year the CAC fined Didi Global, a ride-sharing company, the equivalent of $1.2bn for illegally collecting and mishandling user data. (The move was also seen as punishment for the firm’s decision, since reversed, to go public in America instead of China.) Under the draft rules on generative AI, companies would be responsible for safeguarding users’ personal information.

Plan to worry

The CAC’s proposed regulations come six years after China introduced a master plan for AI that called for “major breakthroughs” by 2025 and domination of the industry by 2030. Progress towards those ends has been mixed. Chinese companies in fields such as AI-assisted image-recognition and autonomous driving, which have much less to fear from the government’s preoccupation with social stability, are doing well. They benefit from lots of public money—in fact, some provide tools that enable state repression. But China is still behind America in terms of investment and innovation. Potential foreign backers have been turned off by American sanctions on some of China’s AI giants. Worse, America has restricted exports to China of the type of cutting-edge semiconductors that power AI, a move that could hobble the industry.

China may have more success when it comes to regulation. According to the master plan, the country is to have written the world’s ethical code for AI by 2030. That is a stretch, but its rules on generative AI are more detailed and expansive than those suggested elsewhere—and are thus influencing the debate over how to handle the new technology. China’s ability to lay down quickly new regulations means other countries will learn from it. One risk is that it moves too forcefully and hinders innovation. But Jeffrey Ding of George Washington University points to the other side of the argument. Noting the ingenuity of China’s internet companies, he says, “Sometimes limits to creativity spur more innovation.”

Still, the idea that China might act as the lead guide when it comes to AI ethics ought to terrify Western governments. They may share some of the same concerns as China, including over misinformation and data protection, but not for the same reasons. Again, China’s experience with the internet is informative. It has steadfastly opposed the notion of the web as a place of freedom and openness. When governments gather to discuss online regulation, China consistently sides with Russia and other tramplers of free speech. Mr Clinton was naive to think that the Communist Party could not pound the internet into submission. It would be naive for Western leaders today to think that it cannot do the same with AI. ■

The Economist