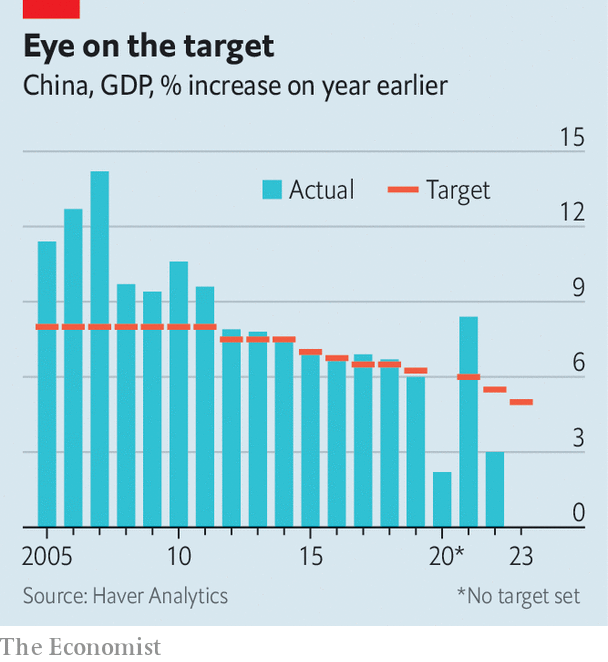

OVER THE next week China’s National People’s Congress, its rubber-stamp parliament, will formally confirm Xi Jinping’s new term as president and the appointment of a new economic team around him. On March 5th Li Keqiang, the country’s outgoing prime minister (pictured, right), opened the congress with his annual “work report”. It confirmed a GDP growth target of “around 5%” for China in 2023, lower than many external forecasts. The target’s conservatism sets the tone for an event which is likely to be about China’s leaders tightening their control over the state.

When China’s government sets its economic growth target for the year, it often faces a dilemma. A balance must be struck between inspiring confidence and maintaining credibility. A high target could give courage to entrepreneurs, making fast growth easier to achieve. But ambitious targets can also be missed, denting the government’s reputation. (They can also induce reckless stimulus spending to avert any such embarrassment.)

Last year China’s government missed its growth target by a wide margin (see chart), largely owing to its costly attempt to keep covid-19 at bay. This year it has prized credibility over confidence. The new target of 5% may seem like a respectable pace to set, roughly in line with China’s underlying “trend” rate of growth. But the economy would normally be expected to exceed that trend comfortably this year, because it fell so far short of it last year. Even if this year’s growth target is met, China’s GDP will remain more than 2% below the path it was supposedly on before the Omicron variant hit China.

The government is nonetheless hoping that China will create about 12m new urban jobs this year. Indeed, the government’s jobs target this year is more demanding than last year (12m versus “over 11m”) even though its growth target is less so. The government may be hoping that China will enjoy an unusually “job-full” recovery, as labour-intensive service industries, like retail and catering, bounce back from the pandemic-era restrictions that hit them particularly hard. It also wants employment to keep pace with the record 11.58m students who are expected to graduate from universities and colleges in 2023.

The undemanding growth target removes any pressure to stimulate the economy further. Compared with last year, Mr Li’s report to the congress contained fewer exhortations to local governments to keep the economy going. He instead pointed out the need to prevent a build-up of new debts. “The budgetary imbalances of some local governments are substantial,” he noted. This year they will be allowed to issue 3.8trn-yuan ($550bn) worth of “special” bonds (which are supposed to finance revenue-generating infrastructure projects). On paper, that quota is a little higher than last year. But it may not feel like it in practice, because local-government spending last year was bolstered by an unusually large stash of bond proceeds carried over from 2021.

The controlling party

The report’s conservatism is in keeping with the emerging theme of this year’s congress, which is about China’s rulers tightening their grip over the state apparatus. After securing a third term as leader of China’s communist party in October, Xi Jinping will be formally appointed once again as president on March 10th. Two days later a number of his protégés and trusted aides will be appointed to key positions in state institutions. Li Qiang, the party’s number two, is expected to replace Li Keqiang as prime minister. He Lifeng, who worked with Mr Xi in Fujian (and attended his second wedding), is likely to become a deputy prime minister in charge of economic policy. He may also serve as party chief of the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank. If so, he will oversee a new governor of the central bank, who is likely to be Zhu Hexin, a commercial banker who also served as vice-governor of the province of Sichuan.

The congress will also approve part of a “relatively extensive” plan to reorganise the relationship between China’s state institutions and its ruling communist party. The plan would give the party more direct control over national security, culture, science and finance, including reviving the Central Financial Work Commission that operated for five years after the Asian financial crisis. The commission would represent yet another attempt to impose more party-led co-ordination on China’s economic-policymaking bodies.

Once this closer control has been imposed on the state apparatus, what goals will be set for it? Mr Li’s work report offered little concrete guidance. Like previous editions, it is a combination of theological boilerplate (“hold high the great banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics”), policy bromides (“We should enhance the intensity and effectiveness of our proactive fiscal policy”) and technocratic factoids (China increased the length of expressways by 30% and drainage pipelines by more than 40% over the last five years).

Foreign investors will be relieved by one thing that was not in it. The term “common prosperity” (gòngtóng fùyù) did not feature. The slogan, which refers to Mr Xi’s campaign to narrow economic inequality, has become synonymous with bashing billionaires and reining in China’s expansive internet companies, like Alibaba and Tencent. (A similar term, gòngtóng fánróng, which is often translated as common prosperity, did appear in an unrelated context.) Like last year, Mr Li patted his government on the back for restraining the “blind expansion of capital”, but this time he was careful to describe those restraints as “law-based”.

The most striking novelty in this year’s report was its nostalgia. Last year’s edition turned from the past to the present by the eighth page (of the English translation). This year’s version did not leave the past behind until the 31st page and then spared only four pages to discuss priorities for 2023. Perhaps because he has reached the end of his career expressway, Mr Li felt unable to offer much guidance on the new team’s plans. He did not want to offer too many hostages to fortune and sought safety in brevity. It is hard to predict the future, especially when you will have no role in shaping it.■

The Economist