Spectacular fireworks lit up the summer sky and the air filled with the smell of sulphur as trails of smoke descended on the crowds in Tiananmen Square. The throng cheered enthusiastically. “Go Beijing, go China, go Olympics,” they chanted. The collective pride was palpable.

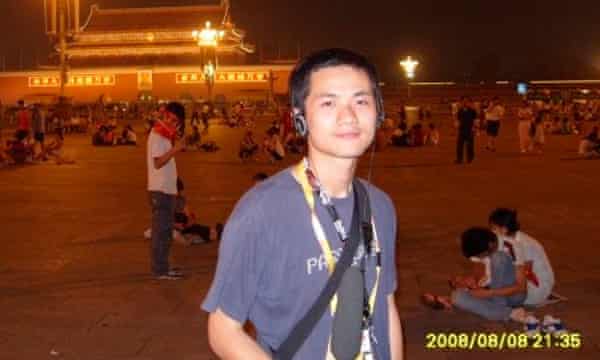

It was shortly after the opening ceremony of the Beijing Summer Olympics, which began at 8.08pm local time on 8 August 2008; the Chinese believe eight is an auspicious number. That evening, Chinese-American Kaiser Kuo was watching from the balcony of his apartment in eastern Beijing. “It was meant to be impressive, and watching as a Chinese person, it certainly was: all the pageantry of history, the flawless performances, the grand scale,” Kuo says.

“But watching through my western eyes, this spectacular event also played into a sense of fear: the robotic juggernaut and machine-like rise. It was intimidating.”

Fourteen years later, China is staging its second Olympics when the Winter Games open on 4 February in Beijing. But the international context and much of the mood music surrounding the event is very different this time.

The 2008 Games were a symbolic moment for China, both as a competitor (sport had long been a means to reclaim wounded national pride) and for the image the event projected to the world. The Chinese capital underwent a massive facelift after winning the bid in 2001 as roads were repaved and subway lines added. Authorities amassed 400,000 English-speaking volunteers to prepare for the influx of foreigners.

The theme song of the Games spoke to this reinvented and reinvigorated China showing itself to the world: Beijing Welcomes You. For many, the Olympic slogan, “One world, one dream”, was a sign that China’s convergence with the rest of the world was inevitable.

Expectations were exceeded, with China winning 51 gold medals and – for the first time – unseating the US, which won 36. The New York Times called the 29th Olympiad China’s “coming out party, a show of its rising economic and political power and its re-emergence as a global power”.

Jacques Rogge, the then president of the International Olympic Committee, said: “The world has learned about China, and China has learned about the world, and I believe this is something that will have positive effects for the long term.”

The 2008 and the 2022 Olympics will both have taken place during epoch-defining global events and shifts in China’s relations with the west. The 2008 Games coincided with the beginnings of the financial crisis and symbolised China’s recognition on the world stage; the 2022 Games will take place during the Covid pandemic and are already overshadowed by the growing boycotts from western capitals.

In the months leading up to both Games, rights organisations seized on the occasion to highlight the treatment of Tibetans and Uyghurs as well as Chinese dissidents. They called for a boycott. In March 2008, protesters in Greece disturbed a high-security ceremony to light the Olympic flame. This month, a London-based unofficial tribunal concluded China was committing “genocide” in its western region of Xinjiang. Beijing’s response to both developments was furious.

A few days before the 2008 Games took place, the US House of Representatives passed a resolution, by 419 votes to one, condemning China’s record on human rights and was accused by the Chinese foreign ministry of trying to “sabotage the Olympics”. The sharp tone has been similar in the run-up to the Winter Games, yet this time the criticism has been backed by more concerted action: the US has staged a diplomatic boycott, with some of its allies following suit.

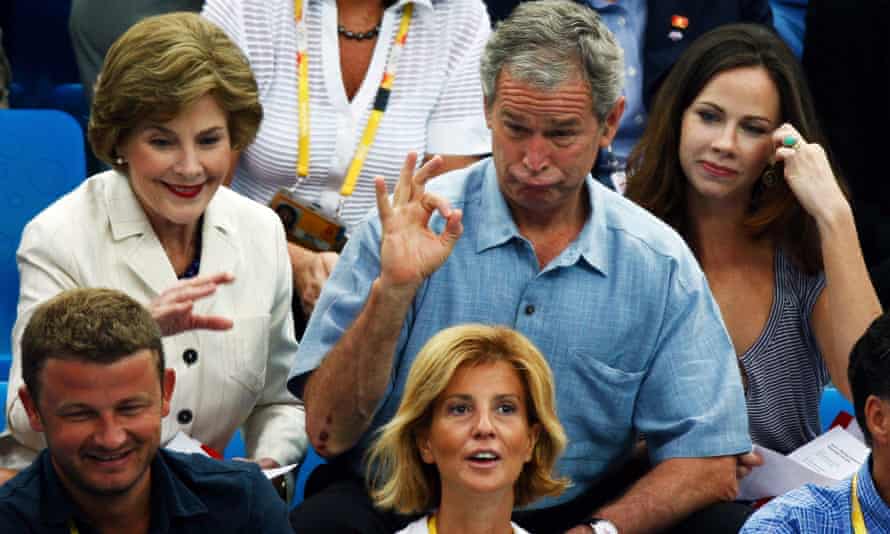

In 2008, the US’s China policy was still dominated by the idea of “engagement”. China was seen as having embarked on a “peaceful rise” and, despite repeated allegations of rights violations, Washington believed China would eventually liberalise. So, on his last trip to Asia before landing in Beijing to attend the Games that summer, the then US president, George W Bush, told an audience in Thailand that while Washington would “stand in firm opposition” to repression in China, “change in China will arrive on its own terms and in keeping with its own history and its own traditions. Yet change will arrive.”

A few weeks earlier, he told departing US athletes in the White House Rose Garden that “Laura and I look forward to joining you for the Olympics. I’m fired up to go.”

That optimism from Washington has evaporated, and 2008 was a turning point, says David Ownby, a China historian at the Université de Montréal, who writes a widely read blog, Reading the China Dream. “The contrast between the beautifully executed Beijing Games and the chaos created by the entirely avoidable financial crisis convinced many Chinese that China was a major player,” he says.

“Since then, the general mood is that China weathers crises better than the west,” he adds, pointing to problems caused in the west by the European refugee crisis, Brexit, Donald Trump’s election, the 6 January US Capital riot, and the pandemic.

A month after the 2008 Games took place, Lehman Brothers collapsed. The US government bailed out Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – two huge companies that had guaranteed thousands of sub-prime mortgages, in the biggest rescue operation since the credit crunch began the previous year.

The fallout of the financial crisis was not just economic, but made clear the reality of a less western-centric world order. In the words of the historian Adam Tooze in his book Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World: “As the appalling scope and scale of the crash was revealed, the financial institutions that had symbolised the west’s triumph since the end of the cold war seemed – through greed, malice and incompetence – to be about to bring the entire system to its knees.”

The financial crisis emboldened China’s confidence in its own system of economic management. That November, the then Chinese premier, Wen Jiabao, announced an unprecedented 4tn yuan (then £375bn) stimulus package, triple the size of the US’s effort. In Wen’s words, the package was “big, fast and effective”.

The deal propelled China’s GDP growth even at the time of a global crisis. And while it also brought headaches for Beijing as easy credit fuelled inflation, the country’s robust growth led it to surpass Germany to become the largest exporting nation in 2009, and in the following year replace Japan as the second-largest economy in the world.

In Washington, China was reluctantly seen as a saviour of the US economy. On her first trip to Asia less than a month after Barack Obama’s inauguration on 20 January 2009, the then US secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, stopped by Beijing. She persuaded Wen to purchase more American sovereign debt. But she also later acknowledged the dilemma this posed for the US. After returning from Asia, she asked the then Australian prime minister, Kevin Rudd: “How do you deal toughly with your banker?”

Some believe the financial crisis and its incremental fallout over the ensuing decade precipitated a shift in China’s global identity and strategy. “[20]08 began this reckoning [in China] with the idea that maybe the United States is actually weakening,” said Rush Doshi, Joe Biden’s China director in the National Security Council this summer.

Chinese perceptions of western weakness are also underlined by the surge in the study of western populism in Chinese academia in recent years, Doshi added. “There’s just so much attention and study on western populism in that period because they see there’s something fundamentally compromising the ability of government to work. They may be wrong about that assessment, but that’s their assessment.”

Mixed with the rethink of its own identity, there was another visible change in China around the Beijing Games, says Kuo, who left China in 2016 after 20 years there. With the exponential growth in internet users every year, the Chinese began to express themselves – sometimes critically of the government – while learning about what the English-language international press was saying about their country for the first time.

“Most of the time they didn’t agree with the foreign press’s coverage of China. And it was then that the Chinese began fighting with westerners online in the comments section of online publications, including the Guardian’s,” Kuo adds. “It was also then when online nationalism began to emerge.”

China has had its own dramas since the 2008 Games. First, the huge stimulus package unleashed that year triggered warnings from economists of China’s own debt crisis. Then in 2012, before Xi Jinping took office, a top-level scandal involving Bo Xilai, a rising political star, sent shock waves through the ruling Communist party and the country.

After Xi came to power in 2013, his anti-corruption campaign took down officials as senior as a former member of the politburo standing committee. In 2018, Xi scrapped presidential term limits, a move that alarmed western capitals. Meanwhile, despite the west’s condemnation of China’s treatment of its Uyghur population and Hong Kong protesters, Beijing has doubled down on its policies.

Albert Leung, the Hong Kong lyricist who wrote the 2008 Beijing Welcomes You theme, is no longer welcome to perform on the mainland after being accused of supporting pro-democracy protesters in the former British colony in 2014. Ai Weiwei, who was involved in designing the Bird’s Nest stadium where the grand opening ceremony took place, is living in exile in Europe.

Parallel to these events inside China, the west has also changed significantly in the decade leading up to the 2022 Games. In the UK, the Brexit vote in 2016 marked a turning point in Britain’s relations with the outside world and sowed domestic division, puzzling many Chinese. In the US, the election of Trump also highlighted domestic tensions, while his China policy amplified the cracks between Beijing and the west and turned an already fraught diplomatic relationship into a zero-sum geopolitical contest.

But perhaps more crucially, the Covid pandemic has strengthened Chinese leaders’ confidence in the country’s political system. “Judging from how this pandemic is being handled by different leaderships and [political] systems around the world, [we can] clearly see who has done better,” Xi told his cadres five days after an angry mob besieged the US Capitol on 6 January. “Time and history are on our side, and this is where our conviction and resilience lie, and why we are so determined and confident.”

“In 2008, China was crying out to be recognised. It wanted to show its wealth, cosmopolitanism as well as friendliness,” says Xu Guoqi, a historian at Hong Kong University and author of the book Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895-2008. “Nowadays, China wants to show its assertiveness. Some in the country go as far as to – perhaps mistakenly – suggest that the east is rising and the west is falling. Hence, in response to [recent] diplomatic boycotts, Beijing said: ‘Nobody cares.’”

Kuo, who now hosts a China-focused podcast called Sinica from the US, says it is hard for him to see how China and the west get out of this security dilemma. “I feel a sense of despair,” he says. “For many years of my life, as we saw things converging, I was very much encouraged. Now, I’ve been very depressed about it. I’ve almost experienced it as a personal failing.”