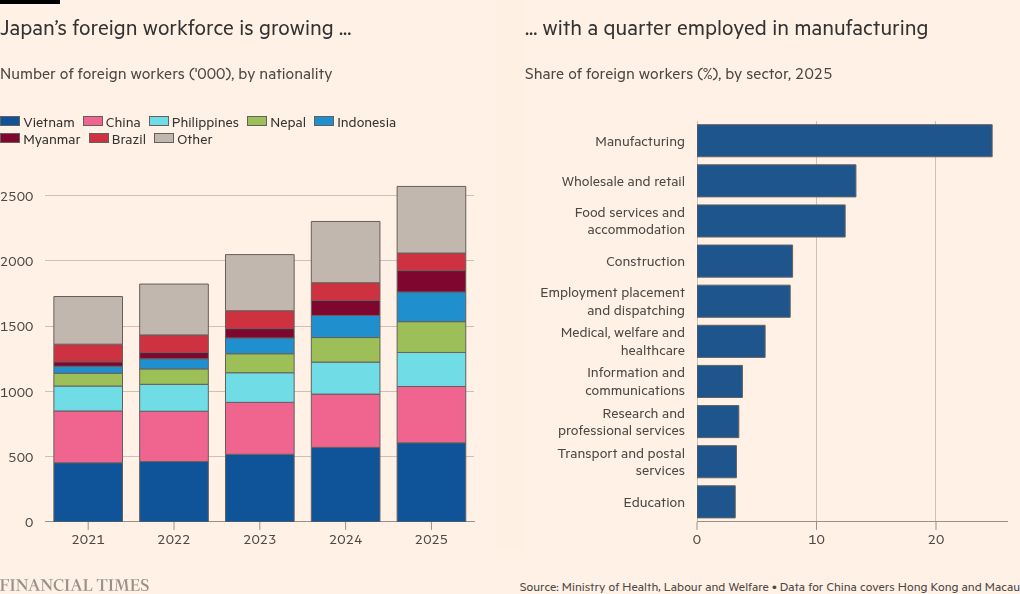

Days into an election campaign fought in large part over issues of immigration and economic anxiety, Japan’s government released data showing the number of foreigners working in the country hit a record 2.57mn last year.

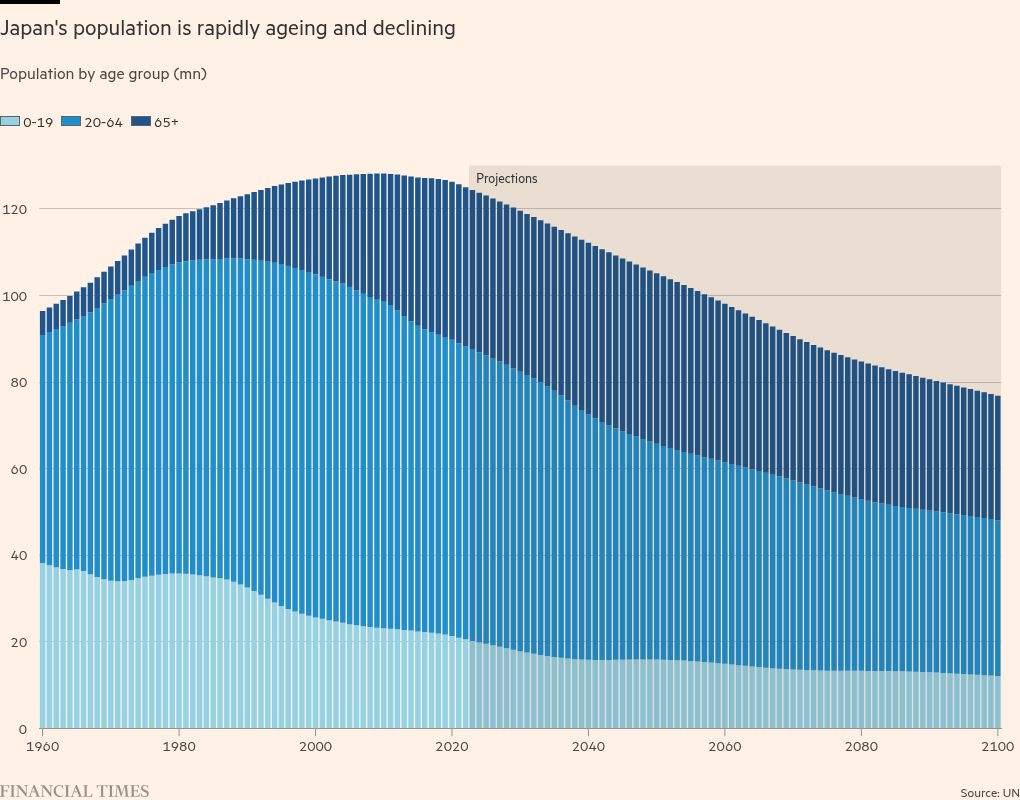

For thousands of businesses across the world’s fourth-biggest economy, the more than 10 per cent annual increase in the foreign labour force in recent years has been a lifeline amid a shrinking and ageing population.

But for Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, and many other candidates across both mainstream and fringe parties, the arrivals pose a threat to social stability to be emphasised in campaign speeches.

“There are increasing numbers of foreigners in this town,” said Tamayo Marukawa, a candidate for Takaichi’s governing Liberal Democratic Party, in a stump speech in Tokyo’s Shibuya city.

Local residents felt “anxious and confused” when foreigners “came into the areas where they live”, the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper quoted Marukawa as saying.

Marukawa’s remarks, along with the tone of the election, come as the reality of foreign arrivals meets a society that has long cherished its homogeneity and assumed that most foreign residents would only be there for the short-term.

Takaichi, an arch-conservative who polls suggest is on track for a comfortable victory on Sunday, has repeatedly stressed she will go further than her predecessors to protect the country from what she sees as the instability that unchecked immigration has brought to other countries.

Takaichi’s administration in November promised to improve immigration systems, review rules on land ownership by foreigners and tackle their alleged non-payment of tax or national health insurance. She has even created a new ministerial position to ensure a “well-ordered and harmonious coexistence with foreign nationals”.

Takaichi says she recognises the value of foreign labour and tourism and draws the line at xenophobia. But some analysts argue that it is her LDP and other conservative and rightwing parties that are most responsible for creating such anxiety in a country where only 3.2 per cent of the population are foreign residents.

“Immigration as a problem is absolutely a made-up debate. It is serving a political purpose and actually people were not that concerned before,” said Koichi Nakano, a political scientist at Sophia University.

While the number of foreign residents was clearly rising, politicians were using them as a scapegoat for problems that they did not have any good solutions for, such as rising prices, the weak yen and slow wage growth, Nakano said.

The LDP had avoided using the word “immigration” in the context of policy out of fear it would crystallise for ordinary Japanese the reality that a large influx of foreigners was necessary and inevitable, he said.

“Takaichi and others still insist on calling it a ‘foreigner policy’. That delegitimises the people coming here to work, and gives the impression that they are only here for the short term,” Nakano said.

Other parties in the election are unambiguously anti-foreigner.

“Japan should not become an immigrant nation!” Sohei Kamiya, the head of Japan’s far-right Sanseito party, told a campaign rally in Kawaguchi, a commuter town north of Tokyo where about 9 per cent of the population are foreign residents.

“We don’t have a proper system . . . politicians just want to accept more and more immigrants. That’s the real problem,” said Kamiya, whose party won a shock 15-seat foothold in the upper house of Japan’s parliament in 2025 after several years of increasingly fierce anti-foreigner rhetoric.

Tas Tevfik, a member of Kawaguchi’s 2,500-strong Kurdish population who runs a kebab shop and a demolition company, has lived in Japan for 22 years but in 2023 suddenly became a target of xenophobic abuse after negative reporting about the community by rightwing press and on social media.

Tevfik’s Happy Kebab shop received dozens of unfriendly calls a day, racist messages were posted on its Google review page and sales dropped by half after a dispute with a YouTuber.

“I’m paying ¥30mn ($191,200) in taxes per year. If those people thought about how much we pay, then they should apologise to us,” he said. “The people at the tax and ward office are so friendly to me — it’s like they’re not from the same country as those other people.”

Far less hostility has been directed at the more than 7,000 people of Indian origin now living in Edogawa in eastern Tokyo.

Yuichi Kondo, the founder of local community group Namaste Edogawa-ku, said a thousand more were arriving every year and there had been some friction over language and noise — the colourful festival of Holi has been banned in recent years — but for the area it was mostly an example of successful integration.

“This is a stable, good community that has built their lives here,” said Kondo. But amid the rising anti-immigrant political rhetoric, an expected influx of less-educated workers required to deal with Japan’s labour shortages could create new pressures, he said.

“We are going to see more workers coming in sectors like construction and truck drivers,” Kondo said. “Japanese people could see them as just labour rather than people who are here to really settle down.”

Sharma, a 42-year-old IT engineer visiting the Hindu temple in Edogawa, said there were sometimes “issues” with Japanese residents, but just the “kind of stuff you find everywhere”. “It’s not like people want to intentionally do the wrong thing, but it happens when lots of people come quickly,” he said.

Yogendra Puranik, who was the first person of Indian origin elected to public office in Japan when he became a member of Edogawa’s city assembly in 2019, worries that the country, by not recognising that it needs to rethink its visa rules, is failing to put in place proactive policies to manage the issues that come with immigration.

“The community in Edogawa works because the people settle for the long term and are educated,” said Puranik, who is now a high school principal in Ibaraki prefecture, adding that policymakers suffered from unfamiliarity with life in areas with many foreign residents.

“Japanese politicians don’t understand the problems with immigration and how to promote integration because they are not there,” he said.