Arguably the standout slide in Nomura chief executive Kentaro Okuda’s year-end presentation to investors showed its legal expenses.

Down from more than ¥60bn in 2022 to near zero over the past three years as it put a series of damaging legal woes behind it, the lower bills are a proxy for broader changes at Japan’s largest brokerage and investment bank.

Since Nomura was badly stung by the collapse of Bill Hwang’s family office Archegos in 2021, losing $2.9bn, it has rebalanced its business — cutting risk and aiming for more consistent returns from more predictable fee-based businesses such as wealth and asset management.

As Japanese markets soar on a wave of optimism, earnings have become less volatile, costs are being reduced and its investment banking and global markets businesses have been overhauled. Last year the bank increased annual profits for the first time since Okuda took over in 2020.

The turnaround helped the mood at Nomura’s centenary party in December yet senior executives acknowledge work is needed to convince investors that change will last.

“We are going to need to demonstrate this sort of consistency for multiple years and we’re also going to have to show that we can do it in down markets,” said Christopher Willcox, head of Nomura’s reshaped trading, investment banking and international wealth management businesses.

“To make people really buy into it you have to demonstrate that over a very long period of time . . . There’s no short-cut.”

For years Nomura, which reports third-quarter earnings on Friday, was plagued by market volatility, scandal and self-inflicted losses. It failed properly to capitalise on its scale in its home market, where it has dominated the sale of financial products to Japanese households.

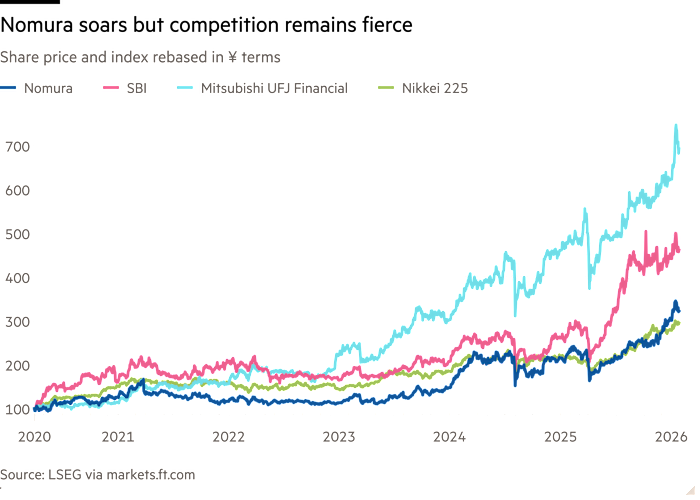

Nomura’s share price has reflected its struggles, falling from ¥2,855 before the 2008 financial crisis — when it bought the Asian and European assets of stricken Lehman Brothers but spent years mired in their difficult integration — to ¥337 just before the pandemic.

But in the past 12 months the shares are up close to 40 per cent, better than the 35 per cent increase for Japan’s back-in-favour Nikkei 225 index. The group’s price-to-book value has climbed above one for the first time since 2016, meaning the market finally values it above the stated worth of its net assets.

For some investors doubts remain. “It’s getting more interesting but we’re not ready [to buy back in] yet,” said a large international fund manager in Japan.

One reason for caution is simply whether Nomura’s turnaround has benefited from good timing.

Inflation has returned to Japan after decades of stagnation, making Nomura’s retail investment products more enticing to domestic savers. On the corporate finance and investment banking side, Nomura has benefited from more acquisitions in Japan, where activists and private equity firms are driving more deals.

Japan’s government and institutions have also become more market friendly, pushing corporate governance reforms. Prime minister Sanae Takaichi is expected to keep that stance if she wins the election she has called for next month.

As markets have surged, some analysts are watching for any build-up of risk. Masao Muraki, a banks analyst at SMBC Nikko in Tokyo, points to growth in Nomura’s risk-weighted assets and its so-called illiquid assets, which increased from ¥21.5tn to ¥23.5tn and ¥1.3tn to ¥1.4tn respectively between March and September last year.

“Positions in securitisation and derivatives have been accumulating, raising questions about capital efficiency and risk management discipline,” said Muraki.

Willcox is adamant that Nomura is not allowing risk to grow recklessly.

“We’re using 8 per cent less [risk-weighted assets, in US dollar terms] than we were in 2020. And we are basically using 2 per cent more leverage ratio than we were then,” he said, referring to a measure of a bank’s core capital as a percentage of its total assets.

“So what is not happening is that the revenues that we’re producing [are] because we’re applying significantly higher capital or risk.”

The challenge for Nomura is to hit its targets of increasing assets under management, especially if markets turn. Japan’s megabanks such as MUFJ are always pushing into Nomura’s territory while newer online retail brokerages such as SBI are capturing a younger cohort of investors.

Nomura’s target is to raise assets under management from ¥101tn as of December to more than ¥150tn in 2030. But the bank does not say how much of that target is expected from fresh inflows and how much simply from market performance, for example the rising valuations of Japanese stocks. (Daiwa, a Japanese rival, says that half of its 10 per cent target for asset growth by 2030 in its wealth management division will be market driven.)

In search of scale, Nomura bought Macquarie’s US and European public asset management business last year for $1.8bn, its biggest deal since Lehman. By pulling in $180bn of assets outside Japan, Nomura said the deal helped its drive to diversify and build reliable revenue streams.

Nomura has also said it wants to grow more quickly in private market businesses such as private equity and credit, where they are targeting acquisitions. The bank has already increased its position in alternative assets such as property, private equity and private credit to hit a record of almost ¥3tn last year.

If it can maintain progress Nomura might break into what Willcox considers a second tier of global banks “on a sustainable long-term basis”. That would put them in the same bracket as some larger European rivals.

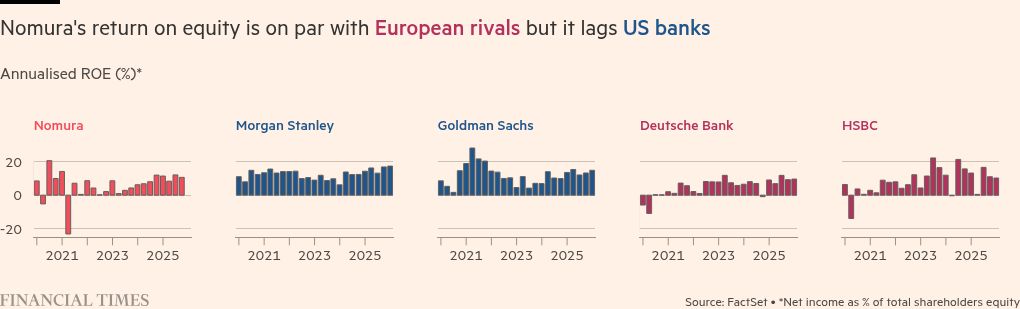

Still, analysts point out that Nomura’s targeted 8 to 10 per cent return on equity is far short of levels at big US banks, which can reach more than double that.

“Even European investment banks like Deutsche Bank have hit higher ROE numbers . . . so we should evaluate the performance of cyclical businesses not only by absolute ROE, but also by relative ROE to rivals,” said Muraki.

Nomura acknowledges its limited resources. In anticipation of a cooling equity market and a “more risk-off environment”, Willcox is starting to shift capital back to macro businesses that he views as countercyclical. But if he had the resources of a larger US rival, he says that perhaps he would not have to deal with that kind of trade-off.

Nomura, he said, has to “make that choice ahead of time and it’s not an easy choice”.