At a heated polo game in New Delhi — a contest between India and Argentina billed as the “match of the century” — fashion executive Adrian Simonetti explained why he believed India had the potential to be a strong luxury market.

“Luxury in India is no longer about labels, it is about belonging to a global lifestyle,” said Simonetti, co-founder and chief executive of La Martina, a high-end leisure sports and polo gear brand headquartered in Argentina.

“There is a new generation with international exposure, strong purchasing power and a deep appetite for brands that carry authenticity,” he said.

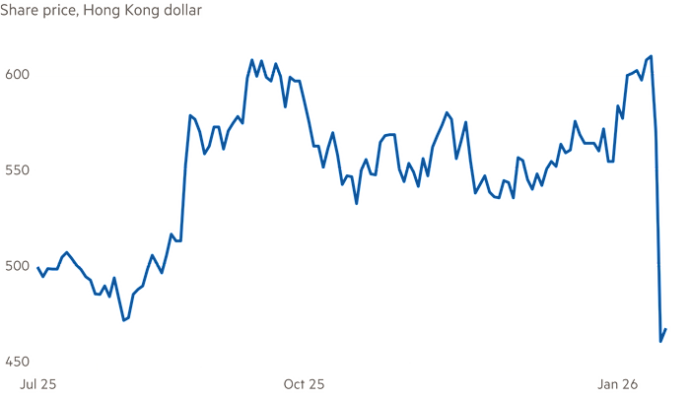

The Argentine retailer is part of a wave of brands searching for growth in India as demand slows in China — which before the Covid-19 pandemic accounted for a quarter of global luxury demand — as a result of a cooling economy and shifting consumer tastes.

But India remains difficult to develop due to logistical challenges, a lack of luxury shopping malls and the tendency of wealthy Indians to travel to Dubai, Singapore or countries in Europe to shop, according to industry experts. High customs duties and bureaucracy have also slowed growth.

Luxury sales across all emerging markets — spanning Latin America, the Middle East, south-east Asia including India, and Africa — are equivalent to the €40bn to €45bn in sales China is expected to have generated in 2025, according to consultancy Bain & Co.

Louis Vuitton, luxury’s biggest brand with more than €20bn in annual turnover, has three boutiques in India, whereas it has dozens in cities across China. Industry experts have described domestic demand in India as “nascent”.

But despite the hurdles, brands see opportunities for growth in India in its growing ranks of millionaires. Groups including L’Oréal and Estée Lauder, which first began selling products in India in 2005, are expanding in the country.

India can “become a bigger contributor in the growth algorithm of the company”, Estée Lauder’s chief executive Stéphane de La Faverie told the Financial Times in October.

Last year, Stella McCartney’s fashion label became the latest addition to a roster of luxury names, including Burberry, Emporio Armani and Versace, brought into the country through a partnership with Reliance Industries, the conglomerate run by Asia’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani.

French upmarket department store Galeries Lafayette opened its first India outlet in Mumbai in October. Kumar Birla, the billionaire chair of the Aditya Birla Group, which helped bring the store to India, described the partnership as “a coming-of-age moment for Indian luxury retail”.

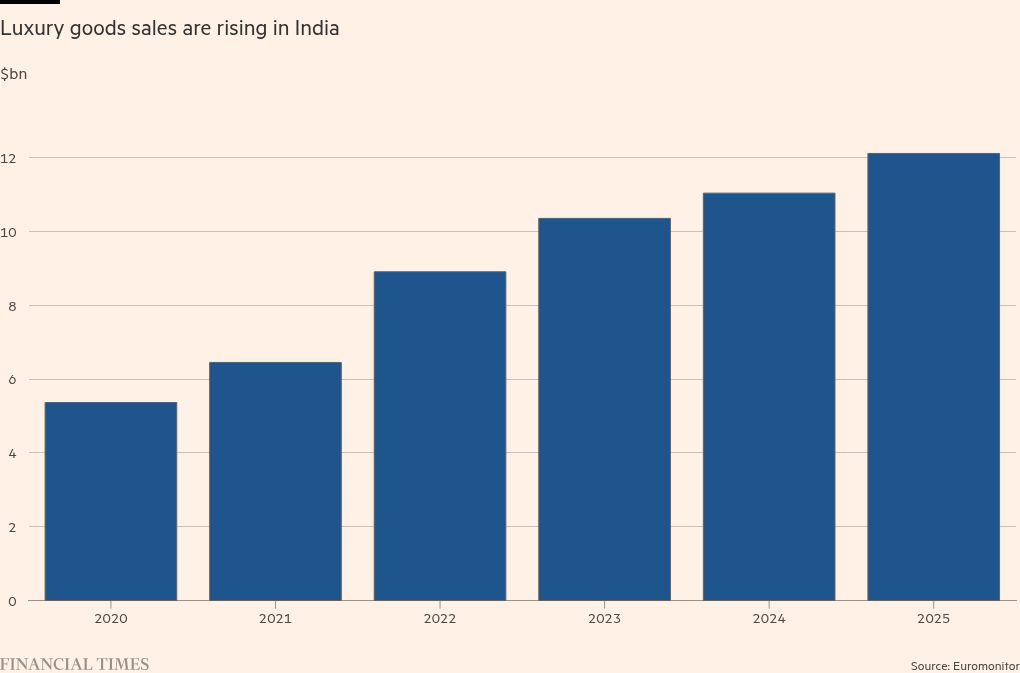

India ranks among the world’s five fastest-growing luxury markets with a current value of $12bn, according to Euromonitor International.

“India’s trajectory is steeper than most regional peers, supported by rising affluence, expanding retail infrastructure and increasing interest in wellness and experience-led luxury,” said Pallavi Arora, senior analyst at Euromonitor.

India’s high import taxes have been a drag on luxury sales in the country. Taxes on items often exceed 20 per cent, alongside domestic goods and services tax rates of up to 40 per cent, said analysts.

New Delhi has traditionally imposed high import duties, earning it the moniker of “tariff king” from US President Donald Trump, who in August slammed the country with a 50 per cent levy. Under some of the proposed trade deals still being negotiated with the US and EU, tariffs on imported goods could fall, potentially reducing prices.

“Many Indians still prefer to buy luxury goods abroad because prices are lower and product choices are wider,” said Euromonitor’s Arora.

Victor Graf Dijon von Monteton, partner at consultancy firm Kearney, said strong growth in India was far from offsetting the weakness in China.

“The baseline is so much higher in China,” von Monteton said, noting that 4 to 5 per cent growth in China’s luxury market would bring more additional revenue than India in its entirety. He noted that China’s luxury market took about 20 years to mature and India was only halfway along that journey.

One Mumbai-based billionaire told the FT they were sceptical luxury would truly take off, pointing to empty marble-floored malls in Mumbai with many wealthy Indians still preferring to shop during trips to Dubai, Singapore, London and Paris.

The billionaire noted that the pool of consumers with disposable income for luxury purchases remains small, with the country’s GDP per capita at about $3,000 in contrast with China’s $13,810, according to the IMF.

Reliance Retail’s foreign brands division lost about $30mn in the past financial year, according to the company’s last annual results up to March 2025.

“Limited scale, high overheads and regulatory hurdles keep many joint ventures unprofitable,” said Ankit Yadav, engagement manager at Redseer Strategy Consultants, an advisory firm.

“High rentals and the scarcity of grade-A mall infrastructure continue to be major constraints for luxury retail expansion beyond [main cities].”

India’s demand for more “accessible” luxury has prompted many brands to launch “smaller-ticket products and limited-edition collections priced 50 to 70 per cent below flagship offerings to engage aspirational consumers”, Yadav added.

For now, von Monteton said Kearney was advising clients to invest in India because “if you’re coming in at a later stage, you’re probably not going to win over the Indian consumer”.

That is advice that Simonetti is fully on board with as he sat among New Delhi’s elite at the polo field. La Martina has 15 stores in the country in partnership with Reliance and has plans to open 11 more by March.

“Polo already resonates strongly with India’s elite sporting culture,” said Simonetti.

“We are also in south-east Asia and in China, but with smaller operations,” he said, “India is something else.”