Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Chinese business & finance myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

China’s flagship overseas infrastructure finance programme the Belt and Road Initiative increased by three-quarters to a record $213.5bn in 2025 as Beijing sought to take advantage of wavering US influence around the world by pouring funding into development projects.

The surge in new investment and construction deals was dominated by gas megaprojects and green power, according to research by Australia’s Griffith University and the Green Finance & Development Center in Shanghai. Beijing signed 350 deals last year, up from 293 worth $122.6bn in 2024.

The boom in investment comes as tensions between the US and China over trade and technology disrupt supply chains and President Donald Trump’s military interventions roil global energy markets.

Christoph Nedopil Wang, a China energy and finance expert at Griffith University and the study’s author, predicted that Beijing’s spending on the BRI would grow further this year, driven by investments in energy, mining and new technology.

“Global trade and investment volatility will potentially spur further investment for supply chain resilience and alternative export markets for Chinese companies,” he said.

The BRI, launched months after Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, is the Chinese leader’s hallmark foreign development programme, seeking to deepen Beijing’s economic influence and trade ties with the developing world. It has made China the world’s largest bilateral creditor, with 150 countries as BRI partners.

Last year’s figures brought the total cumulative value of BRI contracts and investments since its launch to $1.4tn, the study found.

The growth in 2025 was driven by multibillion-dollar megaprojects including a gas development in the Republic of the Congo led by Southernpec, Nigeria’s Ogidigben Gas Revolution Industrial Park led by China National Chemical Engineering and a petrochemical plant in North Kalimantan, Indonesia, led by a Chinese joint venture of Tongkun Group and Xinfengming Group.

“The megaprojects are something we hadn’t seen before,” Nedopil Wang said. He added that developing countries were showing greater trust in Chinese companies to execute deals at a bigger scale.

“Twelve years ago, these companies were a lot smaller. Now with increased size they can take on larger projects — and they need larger projects for growth,” he said. “The willingness to trust China, from the infrastructure planners and policymakers, is substantive.”

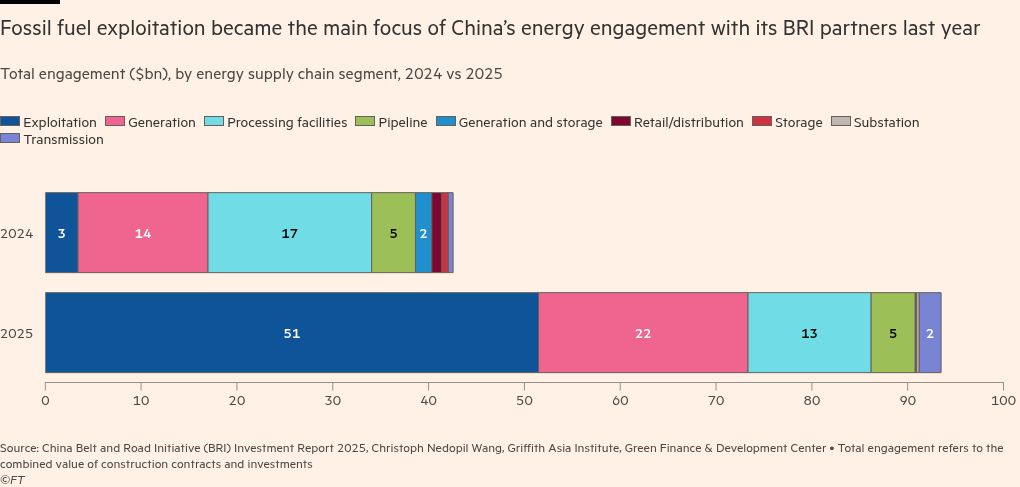

The value of energy-related projects last year was $93.9bn, the highest since the BRI’s inception and more than double the 2024 level. It included $18bn in wind, solar and waste-to-energy projects, underscoring China’s lead in clean technology.

Metals and mining also hit a record at $32.6bn, including a majority of spending on minerals processing abroad, highlighting how Beijing has used the BRI to secure long-term access to resources. That included a surge of investment in copper in the second half of the year. Supplies of the metal have tightened thanks to the boom in data centres to feed demand for artificial intelligence.

Craig Singleton, senior director of the China programme at Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington-based think-tank, said one “emerging pattern” was China’s strengthening of engagement with countries whose resources can help it to exclude the US from its supply chain.

“China’s overseas engagement is increasingly focused on strategic sectors that support self-reliance, supply-chain resilience and technological integration,” he said.

He added that the “lesson” Beijing drew from this month’s US action in Venezuela and threats against Iran was to “reduce exposure to external leverage before crisis hits”.

The scale of the BRI has raised concerns about countries’ ability to repay the mounting debts they owe to Beijing.

A 2024 report by the Congressional Research Service, a US government service, cited issues including unsustainable debt obligations and opportunities to gain concessions, opaque credit and loan terms and a lack of reciprocal market access for BRI partners, as well as investments in strategic sectors and infrastructure which risk civilian and military interoperability.

The CRS also said that western analysts and officials find the BRI increasingly difficult to track and analyse, describing it as an “umbrella initiative” where projects can “be specifically or loosely tied to the effort” while the ability to track offshore financial activity is complicated by China’s use of onshore financing and special purpose investment vehicles.

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong