This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered twice a week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Welcome back.

A grim message today from the EU’s Copernicus observation centre: global warming is set to surpass the 1.5C threshold by 2030, a decade sooner than prior projections had suggested.

“Dangerous climate breakdown has arrived,” said climate scientist Bill McGuire, “but with little sign that the world is prepared, or even paying serious attention.”

Instead, policymakers are grappling with a surge in geopolitical and trade tensions — which threaten to weaken the world’s climate response still further.

New energy, new energy security worries

The Malacca Dilemma might sound like the title of an airport spy novel, but it’s been a central concept in China’s clean energy strategy for more than two decades.

In a 2003 speech, China’s then leader Hu Jintao highlighted a major vulnerability for the country’s energy security. The vast majority of Chinese oil imports were shipped through the Malacca Strait, a narrow stretch of water connecting the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea. A blockade of the waterway by a hostile power could plunge the Chinese economy into crisis.

Reducing this reliance on imported fossil fuels has been a key motivation for China’s charge into the clean energy sector. By many measures, this has been a roaring success. China is now the world’s dominant producer of a swath of low-carbon technologies and intermediate goods, leaving other countries fretting about their own unhealthy reliance on Chinese supplies.

But China’s green energy sector still has significant external vulnerabilities of its own.

On Monday, shares in Chinese copper foil manufacturer Defu Technology fell 14 per cent on news that its $204mn takeover of Luxembourg-based peer Circuit Foil had fallen through.

Copper foil, used in electric car batteries, solar cells and electronic circuits needed for a wide range of green energy applications, is one of many low-profile but crucial cleantech subsectors where China is far from self-sufficient (even as its overall trade balance surges to a record surplus). The country imported $1.3bn of copper foil in the first 11 months of last year — up 8.6 per cent year on year, and far exceeding its exports of the stuff.

Chinese manufacturers are especially reliant on foreign suppliers for some of the most advanced types of copper foil — a problem that Defu’s Luxembourg acquisition would have helped to address. But the deal collapsed after the Luxembourg government said Defu would be allowed to take only a minority stake.

It’s not just copper foil. A January 2024 report on China’s wind power sector by researchers at Tsinghua University found that it remained heavily dependent on imports for crucial parts — including 60 per cent of the bearings that support their rotors, 70 per cent of the transistor modules used to convert power into grid-compliant electric current, and 100 per cent of logic modules used to control turbines in real time.

China’s green hydrogen industry — the subject of an ambitious government growth plan — has been struggling to shed a reliance on foreign-made proton exchange membranes for electrolysers.

Fixing these gaps by acquiring foreign companies’ intellectual property is looking increasingly difficult as other governments look to restrain China’s strength in strategic technologies — as the Luxembourg episode demonstrates.

President Xi Jinping has put pressure on manufacturers to speed up development in areas where the country still relies on imports. “China must keep improving our manufacturing sector, insist on self-reliance and self-improvement [and] master key core technologies,” he said during a visit last May to a plant that makes wind turbine bearings.

State media reported last July that 60 per cent of the bearings for Chinese-made wind turbines were now sourced domestically — up 20 percentage points from the figure given in the Tsinghua report just 18 months earlier.

Yet however strong its technological advances may prove, China’s push for self-reliance in clean energy will be permanently constrained by geology. Much has rightly been made of China’s dominance in the supply of refined minerals used in clean energy applications — but, with exceptions such as graphite and rare earth metals, it must import most of the raw inputs from foreign mines.

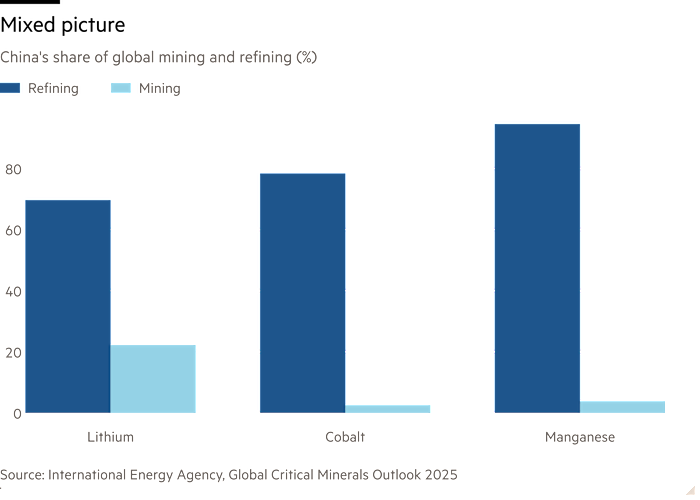

This chart shows China’s contrasting shares of mining and refining of lithium, cobalt and manganese, three minerals used heavily in electric car batteries:

Securing a reliable supply of minerals for the low-carbon energy sector has been a crucial goal of China’s overseas investment strategy, including through Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese companies have been investing heavily in overseas mining operations, with backing from state-owned banks.

But new questions have been raised about the security of this supply in recent years, with Chile, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo — key suppliers to China of lithium, nickel and cobalt respectively — all tightening rules around foreign access to their minerals. Last year China reportedly moved to increase the reserves of several clean energy minerals to its strategic stockpile, suggesting government concerns about potential disruptions to supply.

At a time of geopolitical tension and rising economic nationalism, China is right to worry about its reliance on foreign inputs, just as other nations are justified in their qualms about dependence on Chinese tech. The larger risk for the world — of trade troubles slowing the shift to a low-emissions economy — is obvious.