Chick Olsson has built his animal nutrition business selling salt and molasses blocks to dairy farmers in the Australian outback, but increasingly the agribusiness entrepreneur is targeting the livestock owners of south-east Asia.

“It’s the fastest-growing region in the world . . . These are wonderful nations on our doorstep but we all still think about Europe and the old world,” said Olsson, whose company 4 Season set up a factory two years ago in the historic city of Luang Prabang in Laos to make animal feed.

Last month, 4 Season opened another factory in Thailand. The opportunity presented by the region was huge, he said. “They’ve got a hunger for beef and need more protein for their kids,” he added, pointing to the $28bn school food programme in Indonesia, south-east Asia’s largest economy.

Olsson’s efforts represent a broader Australian push to increase business with south-east Asia, reducing export reliance on China and the US at a time of heightened trade tensions.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s Labor government has appointed 10 Australian businesspeople — including Olsson — to spearhead these efforts, advising everyone from gold miners to blueberry farmers on how best to expand their business in the region.

South-east Asia was “the fastest growing region in the world”, said Nicholas Moore, the former Macquarie chief executive and Australia’s special envoy to the region.

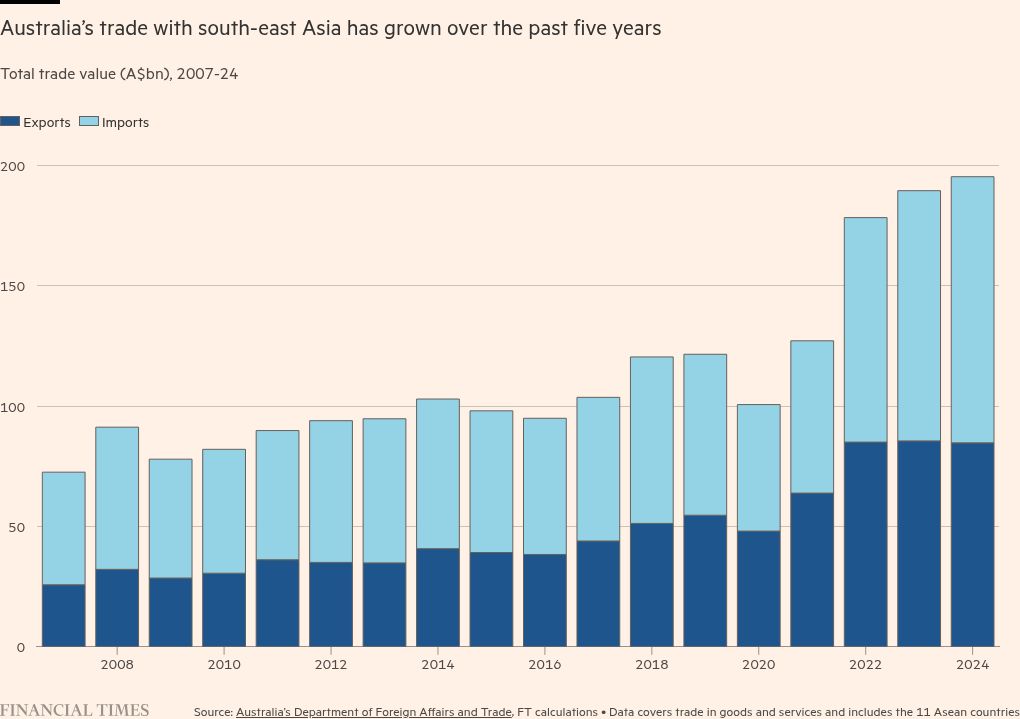

Australian companies and investors who focused on China, the US and Europe risked missing out on the opportunity presented by south-east Asia’s booming middle class and projected GDP growth of between 5 and 6 per cent. “There’s a much bigger opportunity to embrace in the region,” he said, forecasting trade to double over the next 10 years.

Already trade increased by A$5.7bn (US$3.8bn) in 2024, a 3 per cent rise on the previous year, according to government data. Exports of Australian goods and services to south-east Asia reached A$85bn the same year, with Laos seeing the biggest growth at 32 per cent and Singapore, Canberra’s largest trading partner in the region, registering 6 per cent. The Australian government invested A$75mn into Singapore’s clean energy transition fund last December.

Much of the growth has been driven by agriculture. But other sectors, such as mining, finance and manufacturing, are also expanding.

Breville, the kitchen goods maker, shifted its manufacturing base for espresso machines from China to Indonesia’s Batam island, spurred by US President Donald Trump’s volatile trade policy. Meanwhile Lynas, the mining company and the largest non-Chinese rare earths company, refines its metals in Malaysia.

Canberra was keen to encourage more, said Moore, adding that 500 Australian business leaders would have participated in trade missions and delegations to south-east Asia by the end of this year.

Australia has established a A$2bn stimulus facility to boost trade, and in October allocated A$225mn to IFM Investors and Plenary to invest in infrastructure projects. The same month, Monash University in Melbourne announced a A$1bn investment in a new campus in Kuala Lumpur’s financial district.

Moore said increased trade would shore up security as geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific had risen. “That is why the prime minister and foreign minister are so focused on this,” he said. “The peace and prosperity of the region determines the peace and prosperity of Australia.”

“Money goes where it feels safe,” said John Bugg, the Hong Kong-based chief investment officer of Bamboo Investment Partners, which is targeting investments across south-east Asia.

He said that while he had heard more Australian accents in the region in recent years, there were still challenges to investment, such as the ability to hedge currency risks and fears of an uneven playing field against local oligopolies with political influence.

“Confidence in the legal infrastructure isn’t as strong as in the US or Australia,” he said.

Mark Gustowski, founding partner of Mandalay Venture Partners, a venture capital firm focused on food and agtech start-ups, said “chatter” about building stronger links between Australia and south-east Asia belied deeper concerns among investors about long-term liquidity and scalability across a diverse region.

“Australia needs to continue to try to become ‘a part’ of the region rather than a ‘fly in-fly out’ stakeholder,” he said. “There is still much work to be done here.”

Olsson’s company is a testament to the opportunities and the challenges. Establishing even a small factory with just 15 employees in Laos was not easy, he said, recalling that his sons caught dengue.

He also had to custom-build machinery to make molasses blocks, which are then hand delivered to remote areas, where it can take four hours to travel 15km.

Still “my view is if you’re not invested in Asia, then you are mad”, he said. “It’s going to boom in the next 20 years. It’s only going to get more expensive and difficult to expand.”