It was a brief mention in a lecture of the discrimination faced by female members of the Uyghur minority in China’s western region of Xinjiang. But for Sarah Liu, it provoked an incident that made her concerned about the threat to academic freedom from Chinese state influence on British campuses.

After the lecture, she was approached by a Chinese student who questioned the legitimacy of her sources. She then found out later that concerns had been raised with other members of staff.

“They threatened to report me to the Chinese government unless I removed the course material,” said Liu, a senior lecturer in gender and politics at the University of Edinburgh, who says one of her first thoughts was that she could lose her job for “causing [the university] trouble”.

Liu, who is British but lived in China between 2007 and 2008, said it opened her eyes to what she believed was the lack of protection for academics working on politically sensitive issues at a time when UK universities relied heavily on Chinese students.

That “creates a chilling effect where academic staff simply do not research or teach on topics”, said Liu, adding that job cuts occurring across the sector amplified the risk.

Recent events support her concerns. Last month emails from Sheffield Hallam University came to light that suggest a campaign of intimidation prevented the publication of research into alleged human rights violations in Xinjiang.

Liu, who now teaches a China politics course, said other of her Chinese students have also voiced concerns about speaking openly as they fear they are under surveillance.

“I don’t record my lectures to make sure we create a safe environment for everyone,” she added.

Academics from across the UK higher education sector have warned that financial ties to Beijing have led to self-censorship, as the government and universities come under pressure to improve safeguards against Chinese state influence on British campuses.

Andreas Fulda, a China scholar at Nottingham university, said he had endured death threats among other types of online harassment in response to research that was critical of the Chinese state.

“Our universities are, in a way, sleepwalking into a state of super-complex surrender, so to speak,” he said. “Sheffield Hallam is the warning bell.”

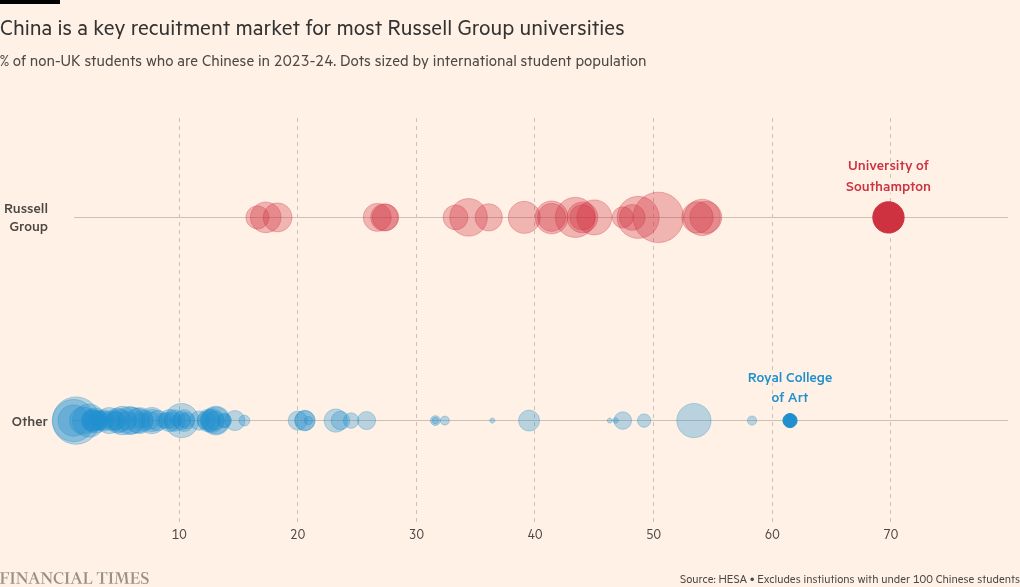

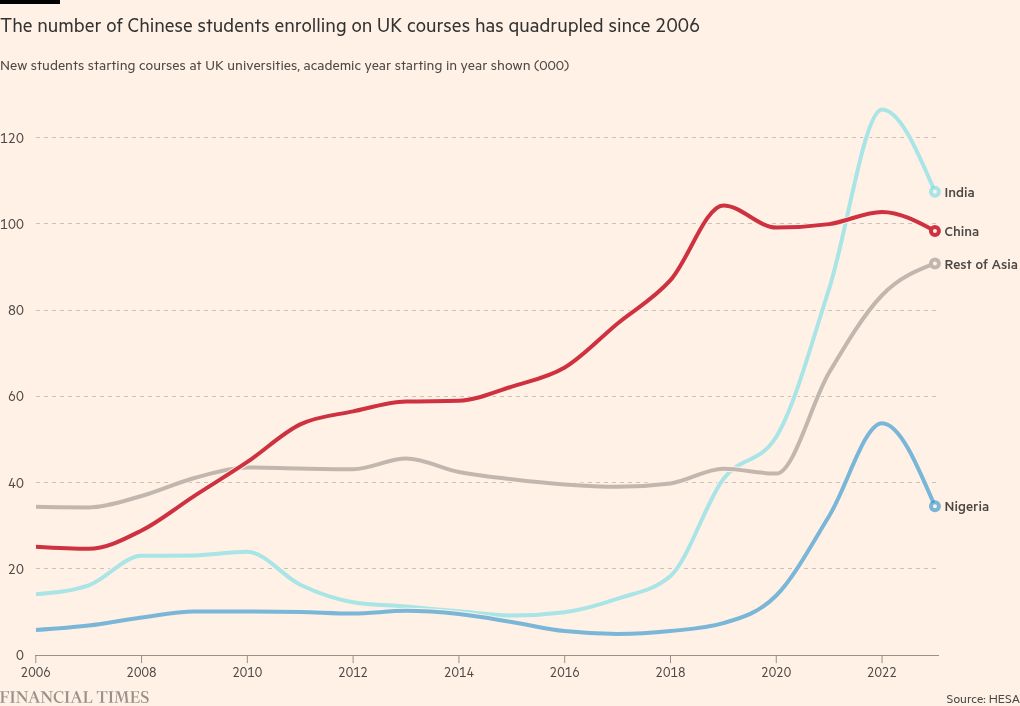

Tuition fees from Chinese students accounted for about 5 per cent of higher education income in 2023-24 and about a tenth of income for the elite Russell Group universities, according to Financial Times estimates that underscore the cash-strapped sector’s exposure to the country.

Meanwhile, Chinese students studying in the UK feel as if they are being treated as revenue sources, according to a Higher Education Policy Institute report that concluded universities needed to do more to help them integrate.

The UK also has more academic ties to China than any European country, according to the Central European Institute of Asian Studies. A third of the 1,518 academic links — such as student exchanges or research collaborations — included an organisation with links to the Chinese military or defence industry, the think-tank found.

Academics warned that rising teaching loads forced them to prioritise projects they believed funding boards would view as low-risk.

“That’s the most powerful form of censorship — self-censorship,” said one. “You’ve done the work for them. But it’s also structural: a mix of dependency, lack of funding and extreme competitiveness in academia that produces this environment.”

“The question becomes not whether the research is valuable, but whether it could hurt income or reputation — which really shouldn’t be part of the equation,” they added.

Another academic warned that UK-based China experts were self-censoring to protect themselves and their families.

“I understand why some colleagues keep a low profile — they may have family in China or worry about access for their China-related research. They don’t want to end up on a ‘naughty list’,” they said.

Tim Law, deputy director of charity UK-China Transparency, said reliance on Chinese student fees and research collaborations could pose “a direct threat both to the UK’s long-term prosperity and to its national security”, noting a “relative vacuum” of guidance from Whitehall.

Education secretary Bridget Phillipson last week deflected calls from Conservative MPs to revive measures proposed by the previous government to tackle Beijing’s influence on British campuses, arguing that the sector regulator already had “extensive powers” to investigate this issue. Ministers were working with vice-chancellors to increase resilience to state threats, she added.

“Across the sector, management is too focused on universities as businesses,” said Sophia Woodman, Edinburgh’s University and College Union president. “Through a wave of restructuring — often on the advice of consultants — they are removing the last vestiges of academic freedom.”

The Department for Education said official guidance made clear universities should not tolerate attempts by foreign states to suppress academic freedom, adding there were “robust” measures to prevent foreign states from intimidating or harassing individuals in the UK.

“We have taken action to put the sector on a secure financial footing so that it can face the challenges of the future, and the Office for Students has been refocused on monitoring the sector’s financial health,” it said.

The Russell Group said that while China “remains a leading source” of students, universities had actively diversified recruitment, adding that institutions took academic freedom “extremely seriously”.

Edinburgh university said it was committed to protecting academic freedom and upholding the rights of students and staff “to learn, teach and debate freely and within the law”.

It added: “Any behaviour that undermines these principles is contrary to our academic policies and Code of Student Conduct, and [is] addressed through the appropriate procedures.”

Beijing strongly denies reports by human rights groups, researchers and UN investigators of human rights abuses and use of forced labour in Xinjiang.

The Chinese embassy in the UK has accused Sheffield Hallam’s Helena Kennedy Centre of releasing “multiple fake reports” on Xinjiang and of acting “as a vehicle for politicised and disinformation-driven narratives deployed by anti-China forces”.

Liu ended up facing no repercussions from the threats as colleagues at Edinburgh were able to prevent students from taking action by using a policy that prohibited them from sharing course material externally, but she remains concerned that her teaching puts her at risk.

“I still fear what could happen,” she said. “Beyond the individual level, the risk is fewer academics engage in research and teaching on these important topics.”

Additional reporting by Chris Smyth