Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

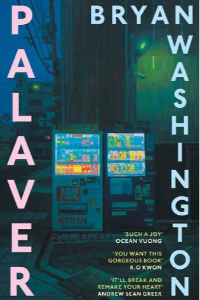

Bryan Washington’s third novel is set in Tokyo, where he lives, and its chapters are interspersed with his photos of the city. The writing has a harmony with these lonely photos, absent of people or at an observer’s remove from them. A city of density coexisting with distance, of submerged feeling: balconies drying clothes; side-street hotels and bar fronts seen as though through the eyes of someone longing to be admitted; cramped cityscapes in dim light.

Such an outsider’s perspective could belong to either the mother or the son who unite in Tokyo after “over a decade” of estrangement, when the mother surprises him with a visit from back home in America. This is as unwelcome for the son as it is unexpected, though prompted by a rare call from him. “You haven’t tried to hurt yourself?” she asks then, and in keeping with the novel’s early emotional restraint and attention to the unsaid, it is the six seconds before he says no, and apologises for calling her, that convinces her he is in danger. “This was when she knew. The son hadn’t apologized for anything in many years.”

Washington only ever names “the son” and “the mother” as such: a formal estrangement that stresses their inescapable bond while reinforcing that theirs is a chilly, almost contingent intimacy. We alternate between their points of view. The son (like Washington) is queer and Black, having grown up in Houston. We sense part of the appeal of Tokyo is putting a lot of distance between his country and his family — his brother is in prison for dealing after tours of duty in Iraq. The son has cut him off for his open homophobia in the past, but his mother finds the many letters the son has written and not sent to him, and we see this estrangement is a cause of intense anxiety and one of the causes of the son’s panic attacks.

He suffers too from the evasions and disappointments that Washington suggests are particular to queer life in heteronormative society, or Black life in America. The mother has been violent towards the son, and in glimpses of the family history we see her guilt at leaving her queer brother in Jamaica for the dream of making it in a richer country, her grief at his death from Aids, and how her anger and guilt at this have affected her relationship with her son, who tells her later she made him “feel worse than fucking dirt for being queer”.

I don’t want to make the book sound depressing, because the dialogue between the son and mother, for all the pain it circles, is delightfully funny and blunt, with an underlying warmth they try and fail to keep buried. The son insists she rebook her flight and go back before her two weeks are up; the mother refuses. He takes her out to a gay bar lined with photos of men having sex. “It’s our first night out in years, but this is where you bring me,” she asks, and the reader might feel he’s being unnecessarily provocative as he continues to drive her away. By the end of the novel we see this as a genuine offering, even if the son’s intentions were then otherwise, for he is inviting her into his community. We trace the son’s improved sense of himself through the friendships and romances that are born there, shown in tender scenes of vulnerable men caring for each other while making light of this with acerbic wit.

If the novel has a weakness it is one bound up in what is at times a strength, that it does not fear sentiment. There is perhaps too much good news towards the end. The mother finds romantic interest from a sweet man. The birth of a child divides the son from his married lover, but the son finds a new man. His alcohol problem neatly resolves. Two minor characters whose sexuality we had not been considering come out to us as queer, and there is something in all of this that risks resolving too easily the tensions between queer life and ideals of the heteronormative family that have provided some of the richest narrative complexity. Washington’s dialogue loses its wit and suggestiveness as his characters try to summarise their epiphanies, and the solution to life’s difficulty is described more than once as the need to keep “showing up”.

The best books of the year 2025

From economics, politics and history to science, art, food and, of course, fiction — our annual round-up brings you top titles picked by FT writers and critics

Inarticulate as this may sound, perhaps there is something to it. The son keeps coming back to the bar and finds a new family. The mother takes a risk and redeems some of the past pain of the relationship with her son. Certainly the author keeps showing up: this is his fourth book at the age of 32. It is a novel of compressed grace, showing the interplay of the past and the present in elegantly suggestive ellipses, hopeful about the possibility of pain being relieved through mutual recognition, through “palaver”. It is often beautiful, and you have to be something of a Scrooge at this time of the year to suggest that a story might have been more moving if it had offered a little less redemption.

Palaver by Bryan Washington Atlantic £14.99/Farrar, Straus and Giroux $28, 336 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X