Good morning. Nvidia’s shares fell and Alphabet’s rose yesterday. Google has been quietly making its way towards becoming “the clear-cut AI leader”, our colleagues reported, including making inroads in chip design. Nvidia’s response: “We’re delighted by Google’s success — they’ve made great advances in AI.” At Unhedged, we are infuriated by our rivals’ successes, but you do you, Nvidia. Unhedged will be off for the rest of the week, celebrating Thanksgiving. We’ll be back in your inboxes on Monday morning. In the meantime, email us: unhedged@ft.com.

Korean stocks

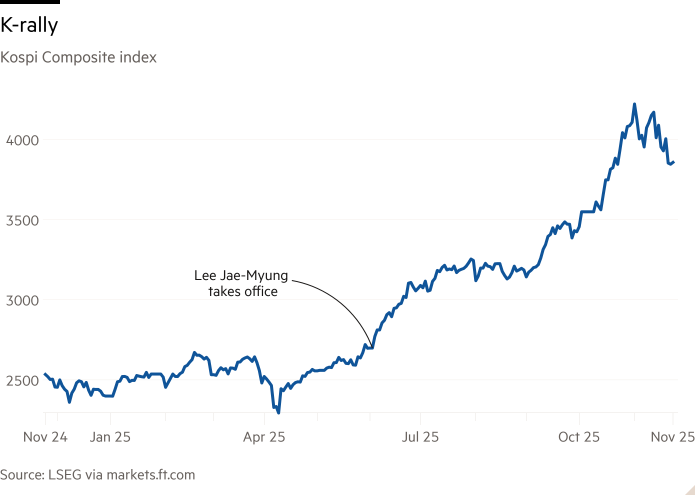

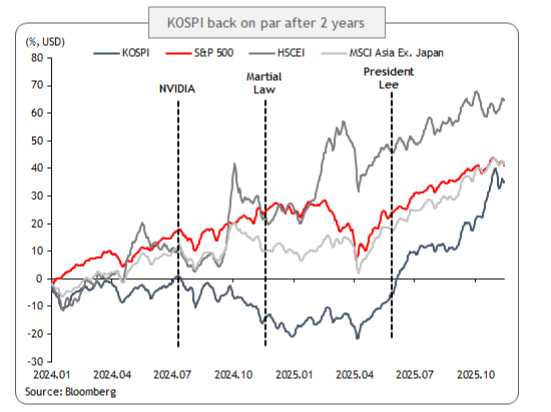

Korea’s Kospi is the best-performing big global stock index this year, with gains of 61 per cent.

Much of the credit goes to the market-friendly policies and corporate governance reforms of new president Lee Jae Myung. And part of the current rally is a catch-up after a difficult few years with weak domestic demand and political turmoil. “Over a two-year period, it’s just in line with the Asia benchmark,” Peter Kim of KB Securities told Unhedged:

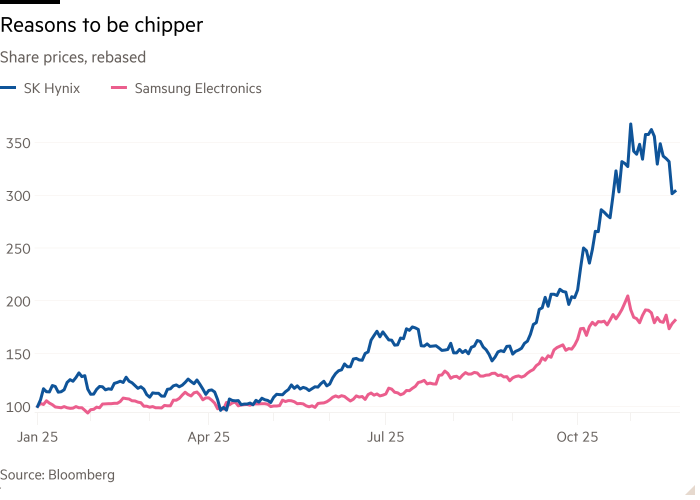

But, just as with the US market, the AI boom has been a big driver. Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix — chipmakers and the two biggest stocks in the index — have rallied 87 per cent and 198 per cent this year, respectively (Samsung Electronics gets about 57 per cent of its operating profit from its semiconductor business).

Is the Korean market as dependent on the AI boom as the US market? In short, yes. Combined, Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix account for about 31 per cent of the Kospi. The two companies, which provide high-bandwidth memory chips to Nvidia and AI companies, sold off alongside Nvidia last week. The MSCI Korea index is even more skewed towards these two names than the Kospi:

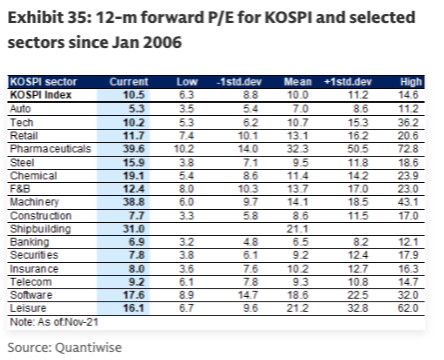

There is a critical difference, however: Korean stocks are, on standard metrics, much cheaper than their American peers. Samsung Electronics trades at a price/earnings ratio of 20, and SK Hynix at 10. In comparison, US-based memory specialist Micron trades at a p/e of 29. A sectoral breakdown from Goldman Sachs shows how cheap the entire Korean market is:

In addition, ongoing corporate governance reform — corporate boards’ fiduciary duty to minority shareholders was made official only this year — provides an upside that is independent of AI. Kim of KB Securities believes the market reforms will provide something of a “safety net” for the Kospi, should the AI trade lose its lustre. Jonathan Pines at Federated Hermes told Unhedged that “half of this rally is general rewriting because of improved governance”. But, he added, regulatory reform will get tougher from here — especially when it comes to family control of public companies:

People talk about ‘can Korea become Japan?’ But I think a key impediment, for now, that will prevent Korea from being as good a market for investors as Japan, is the control issue. You’ve got [about] 90 per cent of [listed] companies controlled by families; if they improve governance on a voluntary basis, they will be hurting their own interests. So you’ve got this inherent resistance in Korea that you don’t have in Japan.

(Kim)

AI-backed securities

The world needs a lot of new AI infrastructure, or at least thinks it does. A recent report from JPMorgan estimates that, between now and 2030, the bill for the build-out of data centres and related power infrastructure will run to more than $5tn. If that’s right, every conceivable flavour of equity and debt financing will be needed.

The securitised debt market is already making a contribution. Moody’s ratings thinks there will be about 30 data centre asset-backed security deals this year, adding up to about $15bn in new financing. On top of that, Moody’s thinks there will be $11bn worth of commercial mortgage-backed securities backed by data centres this year. Combined, that’s almost double the financing volume of last year. And next year will probably be much bigger still.

But the securitisation market may struggle to absorb the amount of debt the AI boom will throw its way. Chong Sin of JPMorgan writes that “while nothing is impossible, in our conversations with investment grade ABS and CMBS investors, one often-cited concern is whether they want to take on the residual value risk of data centres when the bonds mature”.

Unhedged spoke to several ABS investors and analysts this week, and they do indeed have concerns about the long term. As constructed, most securitised data centre loans are issued when the centre has been built and leased to a customer on a long-term contract. The loan proceeds go to eliminate the (riskier) project financing that paid for the construction. Crucially, these are almost always non-amortising loans: the payments do not go towards reducing the amount owed. Instead, they are perpetual financing for what is assumed to be a perpetual asset. The assumption is that at the end of the term of the loan — typically five to seven years — the whole balance will be refinanced.

This combination of asset and financing structure might make you a little jumpy, because the “dark value” of a data centre — its value without a tenant in it — is roughly zero. “It’s four walls with power, water and cooling mechanisms,” as one ABS investor put it to Unhedged. It has no alternative use, and it’s often in the middle of nowhere. “You don’t want to be holding the bag of debt when the lease expiry is around the corner,” the investor said.

This will not be a problem for a few years. For now, there is much more demand for data centre capacity than supply. And tenant leases tend to be longer than the tenor of the debt — as long as 15 years. But if long-term data centre demand is weaker than expected, perhaps because of a technological change, leases will be broken, and contractual protections for owners and lenders vary.

One analyst pointed out that, because of the supply/demand imbalance, the assessed value of many data centres is much higher than the cost to construct them. So the equity investors in the centres might take debt of, say, 60 per cent of the assessed value of the centre, and realise proceeds adequate to pay back the construction debt and recoup much or all of the equity investment. At that point there is no cash equity in the project. If there is trouble, the debt holder will be alone. “What’s the alignment of interest? How much equity is there?” the analyst asks, and the answer is often unclear from the outside.

If the securitisation market is going to absorb as much AI debt as the tech industry needs it to absorb, debt structures are going to have to change. At the very least, proper amortisation of principal is needed.

(Armstrong)

One good read

The opposite of the spirit of Thanksgiving.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.