Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The six-storey INS Land complex in Shanghai is usually thronged with partygoers swarming nightclubs dedicated to hip hop, disco and metal. But this month it made a very different pitch to the city’s young: as a venue for wedding ceremonies.

When the Financial Times visited the site, construction workers were setting up a lavish reception room bedecked with piles of fake grass where couples will register their marriage and celebrate with friends with a themed musical performance.

INS Land is part of an unexpected boom in weddings in China, after officials relaxed rules on marriage registration. In what the state-owned China Daily described as a “youth-oriented transformation of public services” to encourage marriage, couples are now allowed to tie the knot in far-flung holiday resorts and even music festivals. Civil servants are stationed at popular wedding venues to handle the paperwork.

For Chinese officials wanting more couples to marry as a route to boosting the country’s low birth rate, the early evidence is encouraging. In the first three quarters of 2025, 5.2mn new marriages were recorded, according to statistics from the Ministry of Civil Affairs, an increase of 405,000 from a year earlier. The figures were a “modest but notable turnaround”, China Daily said.

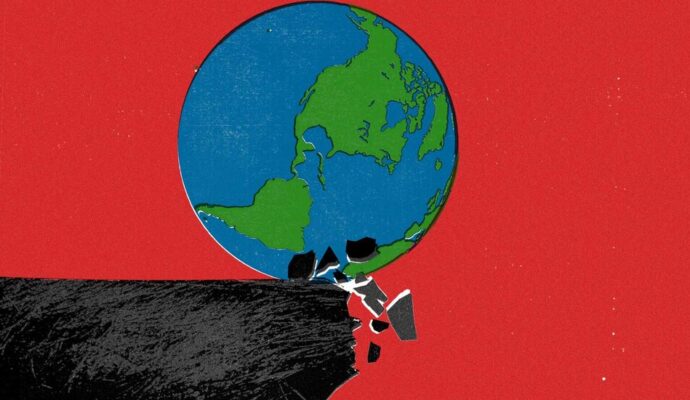

Beijing faces a long-term challenge as its rapidly ageing population is supported by a shrinking pool of working-age citizens. A 2024 UN study predicted that China will shrink from 1.4bn people last year to 1.3bn by 2050, and then plunge to 633mn by 2100, a demographic shift that officials and economists fear will drag on growth.

According to the UN, China’s fertility rate, the number of births per woman, was just below 1 last year — far below the 2.1 needed to keep the population stable.

Until May, couples had to register their marriage in the location of their household registration, or hukou, an inconvenience for millions of migrant workers who live outside their home province. Now, they can get the paperwork without presenting their hukou and register marriages anywhere in the country.

Other elements of a nationwide campaign to encourage young people to marry and have children range from subsidies for new parents to more unique measures such as “love courses” at universities designed to teach students about relationships. Local initiatives offer financial incentives for newly-weds and extended honeymoon leave for civil servants.

Marriage rates have fluctuated since the Covid pandemic and in 2024 fell by 20 per cent to just over 6mn, probably because many couples had already rushed to wed in 2023 after the end of restrictions.

“Officials and state media are searching for good signs that point to a demographic revival,” said Wang Feng, a demography expert and distinguished professor at the University of California, Irvine. “But we shouldn’t get false hope from this statistic . . . The overwhelming evidence shows a long-term decline in marriage and childbearing.”

Persistent pessimism about the economy, falling house prices and job insecurity were feeding into this decline, Wang said. “Couples are not going to get married just because it’s easier to register,” he said.

“The main reasons people don’t marry or have children are financial strain and work stress,” said Chen Xiaoshan, an academic from Shanghai, who married last year. “Raising kids requires endless competition — you can’t afford to lose your job, and most people lack a secure financial safety net. It’s exhausting.”

Even if the regulatory shift does not spark a long-term recovery in marriage rates, it has fuelled a new industry of destination weddings in places such as mountainous grasslands in Xinjiang, tropical Yunnan and beach resorts in Hainan, all competing to host elaborate celebrations for couples seeking an adventurous ceremony.

One of the most popular spots is Sayram Lake in Xinjiang, which has hosted more than 11,000 weddings this year, including more than 9,000 since the rule change in May. Staff were processing about 50 marriage registrations a day during the peak season, one member of staff told the FT, adding that couples who marry there receive “lifetime free entry to the scenic area”.

The area — known for the lake’s crystal waters and the surrounding snow-capped mountains — spans more than 1,300 square km, a number that in Chinese (yi sheng yi shi) sounds like the phrase “a whole lifetime”.

One newly-wed, Lancelot Liu, a 30-year-old Beijinger who works in finance, married earlier this month at one of the capital’s largest conference halls and said he planned to have “at least three kids” — making him an outlier among his generation. “I’m making my contribution,” he joked.

Additional contributions by Wenjie Ding and Cheng Leng in Beijing and Nian Liu in Shanghai