Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Aerospace & Defence myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Australia’s most valuable listed defence company began as the brainchild of two American scientists who originally planned to create a mosquito-zapping laser system for bedrooms.

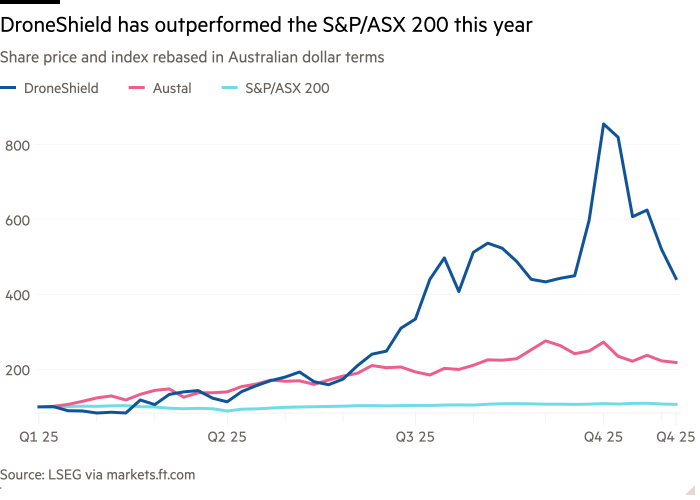

Eleven years on, a pivot from the threat of small insects to that of small drones appears to have paid off. DroneShield, which develops anti-drone systems that have been used on the front lines of Ukraine, is the S&P/ASX 200 index’s best-performing stock this year, rising more than fourfold since January.

The company is now valued at A$2.9bn ($1.9bn), overtaking shipbuilder Austal as the country’s biggest listed defence business by market capitalisation. Customers include militaries, airports, prisons looking to stop drones delivering drugs and weapons to inmates, and local law enforcement looking to protect crowds at big events.

Chief executive Oleg Vornik said the company initially struggled to convince government agencies that small drones posed a significant threat, with many viewing the devices as toys. DroneShield raised just A$7mn at a A$20mn valuation when it listed in 2016. “There was no market” for its products, he said.

But the war in Ukraine and Houthi attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea have highlighted the lethal potential of small unmanned aircraft. DroneShield has been a beneficiary of Europe’s increased defence spending, as kits sold to Polish customers have been donated to Ukrainian soldiers to fend off Russian attacks.

The company is best known for its signal-jamming “drone gun”, but it has expanded to drone-detecting sensors that can be worn on the body and kits that can be integrated into military or civilian systems.

DroneShield sells its products through BT Group in the UK and has signed deals with militaries and domestic security agencies in more than 40 countries including the US, Canada and France. It competes with Denmark’s MyDefence and US groups DZYNE Technologies and Anduril.

As recently as last year, the company derived 70 per cent of its revenue from the US but now generates most of its sales in Europe. Growth has also been rapid in Asia, said Vornik, as countries are “starting to see incursions of Chinese drones on military facilities and critical infrastructure”.

DroneShield reported record third-quarter revenue of A$92.9mn last month, up from A$7.8mn a year earlier, and said it had operating cash flow of A$20mn. It is expanding manufacturing capacity in Sydney and plans to sign up partners next year to start production in Europe and the US.

The stock’s meteoric rise means it trades at an “incredible multiple” compared with more established rivals, driven by the “tailwinds” of increased global defence spending, said Jon Scholtz, deputy head of research at investment group Argonaut.

DroneShield trades at more than 400 times earnings, compared with Austal’s 28, according to Bloomberg.

Scholtz said DroneShield had attracted attention, particularly from retail investors, for being a “pure play” on anti-drone technology. “It’s very niche, so money is very concentrated at the moment,” he said.

The company was founded in 2014 by Brian Hearing and John Franklin, two defence industry researchers who had developed an acoustic system to detect mosquitoes and shoot them with lasers.

They pivoted to detecting small drones using the same technology after seeing potential to sell to military customers, said Vornik, who joined in 2015 after becoming disillusioned with an investment banking career in Sydney.

One of DroneShield’s early investors pushed the company to list in Australia, where regulators had loosened listing requirements to attract high-growth businesses.

Vornik said support for defence investment in Australia had been held back by a focus on environmental, social and governance themes at the country’s largest financial institutions. US fund Fidelity is DroneShield’s biggest shareholder.

“When it comes to ESG, defence is lumped into the same bucket as fossil fuels, tobacco and pornography. That’s not fair to defence,” said Vornik, who noted that his company’s products were not lethal and that it did not sell to China or countries under western sanctions such as Russia and Iran.

“At the end of the day, we are part of the ‘arsenal of democracy’ in selling defence equipment,” he said.