For decades, Hasarun Nisha has voted for the Indian National Congress and its allies in her home state of Bihar. But the 64-year-old labourer will not be able to back the country’s largest opposition party in this month’s state election after her name was mysteriously removed from the voter roll.

“This would be the first time in many years that I cannot cast my vote,” said a shocked Nisha after hearing the news in Parna, a quiet village set among palm tree groves and fields of potato and corn.

Nisha is not alone in losing the ability to take part in a closely fought election in Bihar that could have far-reaching consequences for the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata party.

India’s national electoral commission has purged almost 10 per cent of Bihar’s more than 74mn voter registrations from the roll since June, a process opposition parties say has disenfranchised many people from poor communities.

The cuts, which Congress leader Rahul Gandhi and his local allies have denounced as a “vote chori”, or theft, have become a political flashpoint in a state that is part of the nationalist BJP’s Hindu heartland.

The BJP is currently the largest party in the 243-seat state legislature and hopes its National Democratic Alliance, which includes the party of Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar, will retain control of the assembly after two rounds of voting on November 6 and 11.

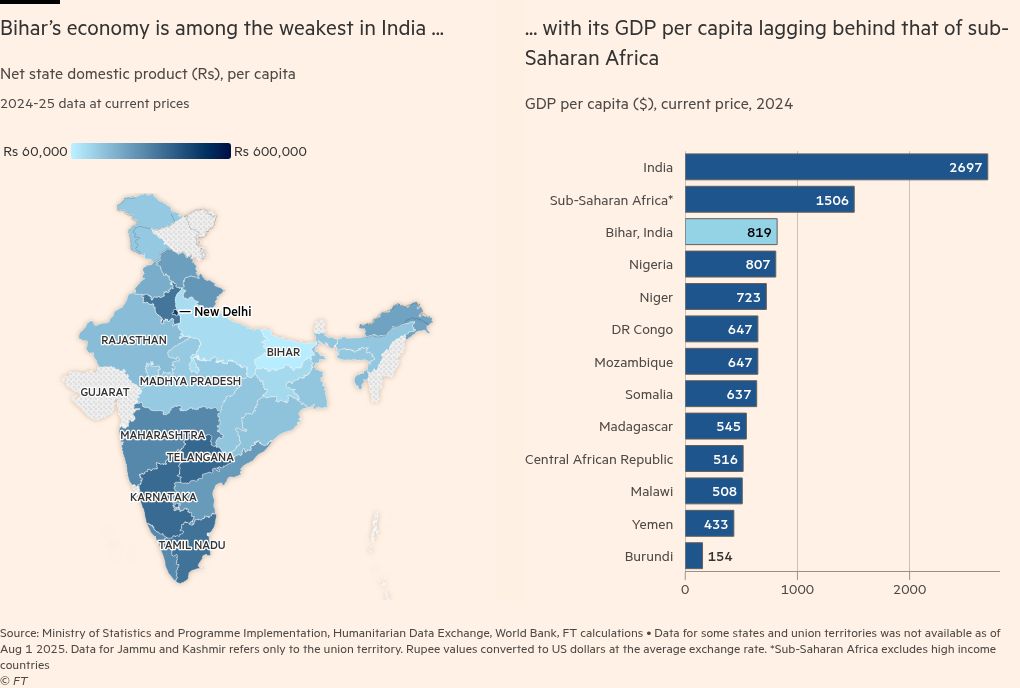

But the BJP is being challenged over its record on support for disadvantaged people in what is India’s poorest state.

“The BJP would like to win Bihar because it’s an important state. It’s a big state. If they win this election they will be in the driving seat to shape state politics, which will create more problems for the opposition,” said Rahul Verma of the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi.

The Election Commission of India insists that the first “intensive revision” of Bihar’s voter roll since 2003 was needed because of “rapid urbanisation, frequent migration, young citizens becoming eligible to vote, non-reporting of deaths and inclusion of the names of foreign illegal immigrants”.

Modi and his allies have accused Gandhi of wanting to give the vote to “infiltrators” — namely Muslims from nearby Bangladesh. But they have not made public any evidence that many foreigners were on the voter roll.

The local electoral commissioner responsible for the area where Nisha was previously registered to vote declined to comment on her case. Bihar’s chief electoral officer and the national commission did not respond to requests for clarification or comment.

National chief election commissioner Gyanesh Kumar said on Sunday the “purification” of voter rolls would be extended to other states — raising concerns about upcoming polls in neighbouring West Bengal, an opposition stronghold that has a significant Muslim population.

The previous Bihar state election in 2020 was a cliffhanger, with the BJP’s NDA winning just 13,000 more votes than Congress’s Mahagathbandhan, or grand alliance. Opinion polls from late October showed the rival coalitions running neck-and-neck.

“Every single vote counts here,” said Yogendra Yadav, an opposition activist who has brought cases before India’s Supreme Court challenging removals from Bihar’s electoral roll. In some cases, voters were erroneously classified as deceased, Yadav said.

In August, Gandhi met Bihar voters reportedly purged from the roll, later posting on social media site X to offer tongue-in-cheek thanks to the electoral commission for giving him the chance to drink tea with “dead people”.

Predominantly agricultural Bihar’s GDP per capita is $819 — lower than the sub-Saharan African average of about $1,400.

An electoral setback in the state would undermine Modi’s national coalition, potentially weakening his government’s hand in dealing with US President Donald Trump’s punitive tariffs.

But victory would solidify BJP dominance in India’s northern belt and provide a morale boost after the loss of its national parliamentary majority in June last year, and ahead of other state elections in the coming months.

“A strong performance for Prime Minister Modi’s BJP . . . would be taken as an endorsement of its refusal to open up India’s agriculture sector in trade negotiations,” said Shilan Shah, an economist with Capital Economics.

Modi has assiduously protected India’s large and politically influential farming sector from US competition in trade talks with Washington.

While state votes are typically led by regional leaders and contested on local issues, the prime minister has been the NDA’s star campaigner, “carpet bombing” the state with more than a dozen appearances, according to a government official.

Amitabh Tiwari of polling group Vote Vibe said the BJP, which leads state governments across northern India, had “a long-term ambition” of having its own chief minister in Bihar.

For now, however, Modi must work with the veteran chief minister Kumar, whose Janata Dal (United) party contested the 2020 state poll as a BJP ally, later joined Congress in the Mahagathbandhan, and then returned to the NDA last year.

Kumar, 74, has run the state for most of the past two decades and is credited with building infrastructure, especially roads, and welfare spending as well as bringing to an end a previously lawless era known as the “jungle raj”.

Modi has also appealed to Bihar’s women, giving out 7.5mn cash transfers of Rs10,000 ($113). Women form an important voting bloc in the state because many of Bihar’s men seek work elsewhere as migrant labour.

“We have been voting for Modi and Nitish because they have given us everything for free,” said Anita Devi, 30, a rural Bihar resident and mother of two who belongs to what is known as a “backward” caste. “We will continue supporting the government that works for people like us.”

Jan Suraaj — a new party founded by Prashant Kishor, Modi’s former poll manager — has urged Bihar residents not to vote “for caste or freebies”.

But caste plays a critical role in Bihar’s politics. A census conducted two years ago found “backward” castes made up a large majority of the state’s population of 130mn, and remained among its most deprived, despite a decade of BJP-led government policies aimed at redressing inequality.

Dhiraj Kumar Sahni, a 38-year-old carpenter from a lower caste, said he had supported the BJP’s alliance in the past, but was not satisfied with the level of development it had brought Bihar.

This time, Sahni said he would vote for the opposition to boost the chances of the Congress candidate, “a fellow caste man”.

“I’m compelled to vote for Mahagathbandhan,” he said. “That’s how caste works here.”