Halfway up the steep trail of Loushan Pass, in the heart of south-western China’s mountainous Guizhou province, a group of 20 or so Communist party cadres, mostly dressed in white short-sleeved shirts, black trousers and black shoes, stand in three neat rows, listening attentively.

Against the backdrop of a regenerated forest, an animated tour guide tells these young officials the stories of sacrifice in the battle that took place here 90 years ago, the mood heightened by dramatic music playing from a speaker at his feet.

Loushan, near the city of Zunyi, is celebrated as the site of the Red Army’s first significant victory over the Nationalists during the Long March of the mid-1930s. Among the martyrs, the guide explains, was an injured Red Army soldier who took his own life so as not to slow down his comrades.

These cadres are part of a growing trend of pilgrimages made by Chinese, young and old. Some trips are sponsored by the state. But many private citizens are also choosing to spend their money and free time on hóngsè lǚyóu, or “red tourism”.

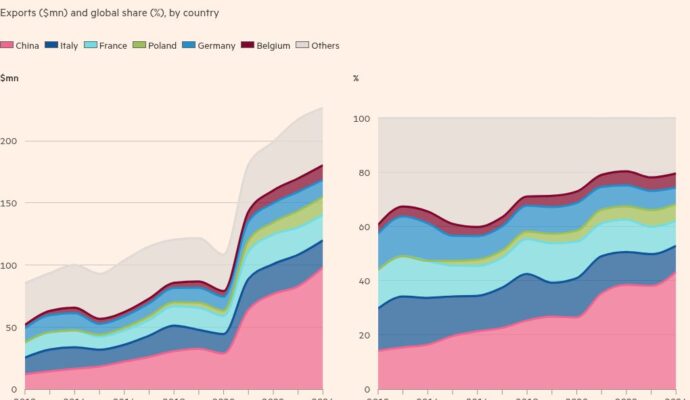

China boasts thousands of official red tourism sites, historical museums and memorial halls. At a time when international travel has yet to fully recover to pre-pandemic levels, red tourism has become a significant part of a domestic travel boom.

While official statistics in this country of 1.4bn people are often problematic, data from multiple corporate travel agencies tracking flight, train, hotel and museum tickets shows the Chinese flocking to red tourism sites in record numbers — according to official estimates, as many as 2bn visits are now made to red sites across the country each year.

The Guizhou city of Zunyi, which has been portrayed in official Chinese history as bearing witness to one of the most pivotal moments in party history, is illustrative of red tourism’s popularity. The city, which is nestled deep in a valley and bisected by the black, meandering waters of the Xiangjiang River, has 6.5mn permanent residents but its population doubles during national holidays.

The area runs deep with red history, including the Battle of Loushan Pass and the Four Crossings of the Chishui River. Perhaps the most important site is a two-storey building of brick and wood in downtown Zunyi, the site of the Zunyi Conference of January 1935.

The meeting, held amid some of the darkest days of the Long March, is celebrated as a turning point for the communist revolution, and for Mao. The story goes that after months of heavy Red Army losses and vastly outnumbered by the Nationalists, Mao, then 41, convinced enough of the leadership gathered at Zunyi to back his military strategies of guerrilla warfare and promote him up the ranks of the senior command — a key step towards supreme leadership that would follow.

Xi Jinping, China’s most powerful leader since Mao, has travelled to Zunyi twice as head of the party, in 2015 and 2021, nodding to the “enduring spiritual legacy” of the Red Army’s time in Guizhou, and noting the importance of Zunyi for the establishment of “the correct” party leadership.

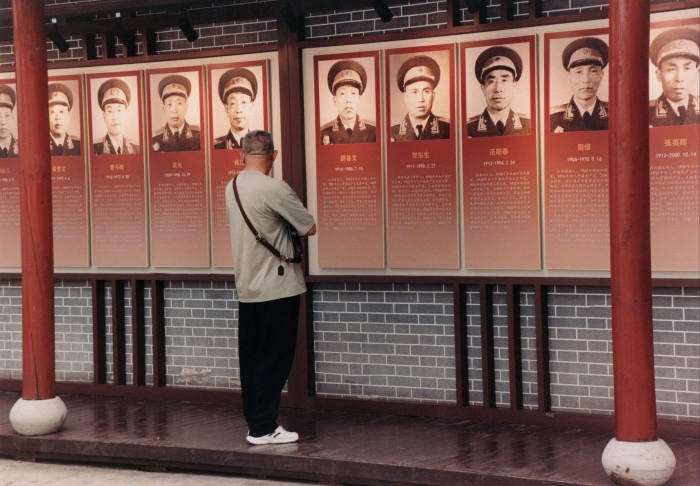

Today, the conference building and adjacent museum display original letters, maps, dispatches, photographs, ragged slippers, rifles and a bugle. Sacrifice, again, is prominent. Among the array is a poem written by a local man who sheltered Red Army soldiers, only to be later killed by the enemy.

When I visited, there were several hundred people flowing through the buildings and surrounding courtyard. The crowd was a mix. There were, as expected, many older people in tour groups, representatives of the 300mn or so people over the age of 60 who witnessed — and in many cases helped forge — China’s march from poverty to a global superpower over their lifetimes. But there were also many younger Chinese couples and families, members of a generation who did not suffer the same hardships as their parents and grandparents, and yet have a surprising zeal for red history. And there were many more groups of cadres, in their white short-sleeved shirts.

One 29-year-old woman from Guizhou’s neighbouring Sichuan province, surnamed Zhang, had travelled to Zunyi with her partner and another couple. They were performing their patriotic duty by visiting historic sites on their first day, she said, and would go shopping the next.

At the museum, Zhang said, she was struck by a display of the Loushan battle scenes, where Red Army soldiers are nestled among the mountains and rivers, hiding among the rocks, firing at the enemy. “You have to see it with your own eyes to truly understand it,” she said. It was a reminder that life in China today was “earned with the blood of our predecessors”, she added. “Children should come and see it”.

Another man in his sixties who had travelled with a small group from Anhui, in China’s east, said he was “deeply moved” by his visit to the conference building and museum. “Our current happiness is the result of their hard work,” he added.

Rowan Beard, an Australian-born tour guide who has taken intrepid tour groups to parts of China, Russia and North Korea, among dozens of other countries, argues that around the world “all museums have their angle and narrative . . . especially when they are about war”.

Beard notes that in Japan, for example, exhibitions may lay claim to giving countries such as Thailand, the Philippines and Korea their “liberation” — yet these nations were brutally occupied by Japan in the first half of the 20th century, their men subjected to forced labour, their women to sexual slavery.

American school students might go to Gettysburg as part of their history or civic lessons. And yet the importance of a singular, official historical narrative to contemporary China appears to go far beyond any obvious parallel, in the west at least.

What should be remembered — along with what should be forgotten — is among the most sensitive and important propagandistic tools deployed by China’s party ideologues obsessed with the omnipresent question of their legitimacy to rule over the country. Museums and revolutionary sites have long been seen as part of a system of participatory propaganda, which has similarly been deployed in earlier eras, including in Soviet Russia and East Germany.

Joseph Torigian, one of the world’s leading experts on the Chinese Communist party and author of a recent biography of Xi Jinping’s father, says red tourism is viewed by the leadership as essential in “inoculating” people against western ideological infiltration.

“That means using history as moral education, it means winning people over to the cause by increasing their idealism and conviction,” Torigian adds, noting that Xi, like Mao, believes “young people are the point of maximum vulnerability”.

History in China can sometimes be a case of amnesia rather than remembrance. As with most public discourse related to Mao in contemporary China, at red tourism sites in Zunyi there is no visible attempt to confront the horrors of the Great Leap Forward or the Cultural Revolution, nor acknowledge the tens of millions of people estimated to have died as a result.

At the museum gift shop, the most expensive item, at Rmb8,600 (about £910) is a bust of Mao with a small red scarf. In another example of the coexistence of revolutionary piety and cheerful consumerism, he sits among a trove of memorabilia, including coffee cups, drink bottles and soft toy figurines of Red Army soldiers.

At Chishui River Memorial Tower, a tribute to the Red Army’s daring series of four crossings of the Chishui in 1935, Li Ziliang, a local guide aged 40, suggests that at some level the party’s version of history has become truth for many. Unpaid and self-taught, Li patiently waits for visitors, ready with an earpiece microphone connected to a speaker at his hip. “Chairman Mao”, he tells us, was a “truly remarkable” leader.

The crescendo of Li’s tour is an operatic recital of Mao’s poem, “Loushan Pass”, which is learnt by all schoolchildren in China and concludes with this description of the area, which translates roughly into English as: dark-green mountains, roll like the sea, the fading sunset, blood red.

And yet, despite all the propagandistic underpinnings, poignancy remains along the red trail. Further down the valley from the Loushan Pass, there is a small hillside cemetery. The graves are for about 50 souls, not only soldiers who perished in the revolution but also a small number of the tens of thousands of Chinese killed in the country’s war with Vietnam in 1979.

The cemetery’s security guard, a likeable veteran of the Sino-Vietnamese war, surnamed Ma, with a wispy beard, improbably black hair and a long wooden pipe for smoking his cigarettes, chatted away warmly. Beyond keeping guard here, he travels south to martyrs’ cemeteries in Yunnan and Guangxi each year.

“It’s not a matter of glory; it’s all our duty to defend our country,” he said. “I simply feel deeply for our comrades who died on the battlefield.”

Edward White is the FT’s China correspondent. Additional contributions by Wang Xueqiao

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning