You can enable subtitles (captions) in the video player

Well, prime minister, Singapore is, perhaps, the most globalised country in the world. And you like rules, you like precision, you like mathematics.

We like stability.

You like predictability.

Yes, of course, who doesn’t? You like stability. You must be having to adapt to a new world order. Tell me a little bit whether this requires fundamental change in the way that Singapore operates.

We are, certainly, in the midst of a great transition to a multi-polar world, a post-American order and a multi-polar world. No one can tell how the transition will unfold, but there is no doubt it will be messy and unpredictable because America is stepping back from its role as global insurer, but there is no other country that’s able to, or willing, to fill the vacuum.

So we are in an uncomfortable position where the old rules do not apply any more, but the new ones have not been written. And we must brace ourselves for more turbulence ahead. So what are we to do in this environment? I think we cannot afford to just wait for things to happen, or hope somehow that things magically will fall in place. We have to take actions now, plan now, and start taking actions to invest together in tackling the problems of the global commons, or in building new trade connections, and keeping up the momentum of trade liberalisation. So that’s something that Singapore is keen to do. We can’t do it alone, but we will do it with other like-minded countries.

Can you envision a world without the US?

The US may not be able or willing to join these plans now, but we have to press ahead. And hopefully in time to come they will come along as well. But given the uncertainties and the unpredictabilities, we cannot just leave things to chance. We have to start taking actions now to lay the foundations of the new multilateral architecture.

But there are two views that the next few years are more of a passing phenomenon, or that there are deep structural changes in the world order that we are now living. You are in the second camp.

Yes, we are. We are because we believe what has happened in America is not just a temporary phenomenon. It reflects broader change in political culture and also in American society itself, a feeling that America has not benefited from the current global order that it had put in place. And it is not prepared to do as much of the heavy lifting to keep the order going. And I think that goes beyond this administration.

Is some of this sentiment justified? Does Donald Trump have a point when he says that the US has been taken for granted, that it’s been taken advantage of?

Some of it may well be justified in the sense that there may well have been free riders, so to speak. And countries do need to do more to invest in their own economic security and also stability. We do that in Singapore. We have never taken it for granted. We have consistently invested year by year in our own security, in our defence, and also facilitated America’s presence in the region.

Certainly, what the Trump administration has done is to motivate and catalyse many countries to do this self-reflection. And you see that happening now. More countries are indeed investing in…

There are certainly self-reflection. You see it. You see it in Europe and people are taking matters into their own hands.

Alternative, while there may be truth in some of what Mr Trump has said, and the positive result of this is countries taking more responsibility and spending more on your own security, we worry that the consequence of these actions will also mean, as I just said, a weakening of the global order today. And we think there’s no going back. There will be a new multi-polar world.

Multi-polarity itself does not provide a stable framework for countries to work together, to co-operate and to ensure shared prosperity and security. So we have to think about what we can do together to engender that.

Does this multi-polarity mean spheres of influence? Because you often look at the way the US administration operates, and it looks like what the president prefers are three strong countries. That wouldn’t work very well for Singapore, would it?

We hope it will not end up like that because if the world ends up in exclusionary blocs and spheres of influence, I think it will be more dangerous and unstable. So from our point of view, multi-polarity should still have a way to bring about global connections. We would prefer a world where Asean in southeast Asia, we are a platform that allows for open and inclusive engagements with all the major powers.

Do you think Asean could become a more credible bloc politically, but also economically? Certainly, we have ambitions to do so.

I know that this is what Singapore hopes for, but are there concrete moves to make it such?

I wouldn’t, first of all, belittle the achievements of Asean. Southeast Asia is a very diverse region, highly complex, made up of so many different ethnicities, languages, religions. It used to be called the Balkans of Asia because of the geographical fragmentation and the potential for instability. And yet, all these decades since the end of the Vietnam war, southeast Asia has been able to maintain relative peace and avoided major conflicts. And a lot of it is credit to Asean.

Asean is certainly not perfect, but it is indispensable, and we are continuing to build on the foundations that have been laid. There are plans to accelerate Asean integration to make ourselves a more attractive and competitive single market. And in some ways, the tariffs imposed by America have indeed catalysed and motivated Asean leaders to come together with more urgency on this endeavour.

So you got off pretty lightly. But of course, the US does not have a trade deficit in goods or in services with Singapore; so you got 10 per cent. It’s not the same for your neighbours. They have some of the highest tariffs. So there is a growing sense in the region that the US under Trump has turned its back on southeast Asia. Do you agree?

The actions of the tariffs have certainly impacted America’s standing in southeast Asia, there is no doubt. But I would say all southeast Asian countries still recognise that America remains the largest investor in the region, not China. China is the largest trading partner. But as far as FDI flows are concerned, America remains the largest investor. America still has significant stakes in Asia, and all of us in southeast Asia want to maintain good links with America. And that’s why many countries have had extensive negotiations with the US. And eventually, they have landed on slightly lower tariffs.

More around 19 per cent. It’s interesting how now we think of 10 per cent or 20 per cent, as, practically, as relief.

I agree fully with you.

But we started with nothing.

Exactly. So from our point of view, the correct figure is zero per cent but 10 per cent has become the new normal. What to do?

You could though still suffer from semiconductor tariffs on and pharmaceuticals. Are you in discussion with the US?

We are.

And do you think that you will get exemptions?

It remains to be seen. We are in discussions with the American officials on this. But from what we understand from some of the large American firms, like the pharmaceutical companies, some of them on their own have already negotiated their own exemptions because they are investing back in America.

So these are the pharmaceutical companies in Singapore? That’s right.

They’re American companies. They’re investing in America, so they get their own exemptions. That’s right. So we are looking at this in greater detail also to understand fully what’s the impact on our economy.

You’re a logistics hub. There are a lot of re-exports from Singapore. And supply chains have been disrupted because there is pressure also from the US to remove Chinese elements from these supply chains. Have you felt this pressure and what impact has it had?

Not so much on the overall flows, because if you look at global figures, trade flows continue. They are just being reconfigured into new patterns of trade. And so long as they are continuing, especially in Asia, Singapore can remain a relevant node. And we see that continuing to be the case. And we are determined to remain at the centre of these global patterns

I know that you are under pressure to stop US advanced chips from getting to China, advanced chips that you get in Singapore. What are you doing to stop these flows?

Well, our position is very clear. We’ve established a business hub on the basis of our reputation for rule of law and trust. And so we are determined and fully committed to maintain the integrity of our business environment. We will not tolerate businesses violating our laws. We will take strict actions. And when it comes to export controls, we will also not condone businesses or individuals taking advantage of their association with Singapore to circumvent the export controls of other countries.

So where America is concerned, what we have done is put in place robust arrangements so that the US government can take actions, investigate companies of interest in Singapore if they so wish. And we will also extend similar arrangements for other countries if they would like also to have the same treatment when it comes to their export controls, because nowadays export controls is not limited to America only.

Are you surprised that economic growth hasn’t really suffered? Tariffs were supposed to do a lot of damage. And yet whether you look at the global economy, the recent IMF report, or, indeed, in Singapore, economic growth has not yet been affected. Did we get it wrong?

No, I don’t think we got it wrong. I think there are several reasons for it. One, the actual rollout of the tariffs have not been as high as what they initially were indicated to be. Second, there has been a lot of front-loading of activities, which has dampened the impact. And third, generally speaking, because of AI, because of new technologies, the rest of the economy has been quite resilient so far.

But there will be an impact. I think we already start to feel it in our own economy. In many ways, we always say the Singapore economy is like the canary in the coal mine. Because we are so open and so exposed to the external environment, we are the first to feel it when the external environment starts to weaken. We didn’t feel it in the first half of this year.

So how are you feeling it now?

We are starting to feel some slowdown now as we approach the second half of this year. Because of uncertainty, businesses are holding back on new investments and new hiring. And we are starting to see a general slowdown in business activities.

I’m just wondering how you and your neighbours navigate the tensions between the US and China. There may be a trade deal. There may not be a trade deal. One thing it’s on, one day it’s off. How difficult is it for you?

I suppose we have to take a step back and look at, first of all, the US and China relationship itself. It’s the most consequential relationship in the world, and it’s also the most dangerous fault line in international relations. For now, you can see both countries wanting to insulate themselves from each other. There are also many interdependencies between them. Their economies are deeply intertwined, and they are looking at potential chokepoints to use as leverage.

But when one economy squeezes, the other squeezes back right away, so you end up in a path and a dynamic of mutually assured destruction. We see this happening already even now. And furthermore, when one side starts to weaponise a particular dependency, it just motivates the other to look for alternatives. So when America puts controls on chips, China will start looking for workarounds because you can use lower-end chips as workarounds.

And China will start looking to become more technologically self-reliant. And when China puts controls on rare earths, I think all of us will start to realise that these are not so rare, after all. And America and its allies, I’m sure, will look for alternatives. These things will happen. It will take time. But the economist in me says that we should never underestimate the elasticity of supply. So when you look at these sorts of dynamics and the consequences of actions, I think America and China may well come to a new modus vivendi. Think about how they can coexist with one another, even while they compete intensively. It’s not easy to see how this may arise… Yes.

…very soon.

I’m trying to imagine what you are describing. If it’s unstable in some areas, it will be unstable in other areas. You often hear the Chinese saying that they look at the relationship as a whole, and they cannot compartmentalise it. Whereas the US prefers to compartmentalise. So do you think they’ll get a trade deal in the next few weeks?

We hope so. It may not be a strategic agreement that resolves everything, but even some form of a guardrail to manage the economic relationship in trade is better than nothing. And if the US and China continue to coexist and not end up with a full decoupling, which is going to be highly damaging to both economies and also highly destabilising for the entire global economy.

So if they can find ways to coexist, going back to your earlier question, Singapore, and all of the Asean countries, will be able to navigate this new environment. We will be able to, therefore, continue to have relations with both America and China.

Do you think that a lot of the US sort of economic nationalism, the America First strategy, is leading more to a China First strategy? And in some ways giving them this impetus to produce the chips themselves, to make themselves even more independent, and, paradoxically, stronger.

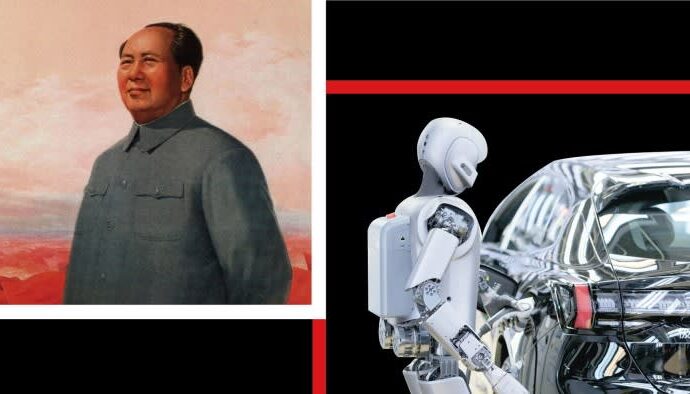

You can see growing confidence in China throughout its entire society at its own developmental model. China’s rise gives rise to a lot of unease in many parts of the world, not just because of it’s a rising power of tremendous scale, but because it’s a power with a different economic model and political system. But I think the world must realise that China will not converge with western norms, and it will find its own path to modernity.

And while there’s still tremendous catch-up growth, because its per capita GDP is just one fifth of America’s, in some areas it’s gone beyond catch up. It’s a technological leader in many areas, in advanced manufacturing, in renewable energy. So we have to contend with and accept the reality that China is not just a rising power, it is a risen power. And the moves that it has made in recent years, I think, just demonstrate that China itself recognises its growing weight, and its thinking about what responsibilities it might exercise as a leader in the global system.

For example, it recently decided to forgo its special and differential treatment provisions in the WTO. In just this past year or so, it has doubled down on its support for global institutions. And I think these are examples of how we have to embrace the reality that China will be a key player, and potentially a key leader, in this new global system.

But doesn’t a country like Singapore then have to make a choice? Because you have navigated a strong political defence relationship with the US and a very strong trade relationship with China. Do you not feel that you are reaching a point where this balancing act doesn’t work anymore? Having said all that I just described of China, we are talking about China today still not being able to, or willing to, replace America’s role in the global system. Because it’s not quite at the same level as America. It’s still a middle-income country with a lot of domestic challenges. So there is no new global leader yet emerging, and we are in this very messy period of transition.

Yes.

And this…

So what does Singapore do then?

Therefore, in this very unpredictable, messy period of transition, which can continue for years, maybe more than a decade, I think we will have to work with like-minded countries, as I said just now, find ways to preserve and reinforce the multilateral frameworks that matter.

So describe to me a little bit this sort of multilateral system that you see. I know that there’s a new grouping that you are promoting with other smaller countries. How do you see that system working and surviving?

The efforts are multi-pronged. One, we have to reinforce and reinvigorate existing institutions, like the WTO. For example, in the WTO the consensus decision-making process, which is a treasured principle, has become a recipe for paralysis. We have to change that. We have to find ways for plurilaterals to take off in the WTO.

You need the US for that, though.

You do, so we’re not discounting the role of America. We’re saying some of us should start moving, keep the momentum going. And in time become, even if America is not willing to or able to make a decision today, maybe down the road it might. And so we have to do that in terms of refreshing global institutions, which we are doing. The second front is to look at path-finding initiatives. New initiatives which we are working on too with like-minded countries. So the future of investment and trade partnership, which…

That’s the one with the UAE?

That’s right.

Yeah.

We bring together small and medium trade dependent economies because we are all alike in wanting to uphold a rules based trading system, and we can come together to push the frontiers for new initiatives. Amongst these 15 or so economies, we already are virtually tariff free. So the point is not to come together to do a FTA [Free Trade Agreement] but to think about what new ideas we can put on the table, including facilitating investments, making it easier for businesses to inter-operate across our economies by standardising rules, regulations, customs, documentation, and enabling using technology as an enabler with electronic invoicing, documentation, data flows. These sorts of things.

And if we can have new initiatives like that in time to come, we might be able to multilateralise them as part of WTO precepts.

You are a massive investor in the US…

Well, we are an investor.

…and around the world. When you hear of the attacks on the Federal Reserve, when you see the unpredictability of economic policy, does that make you less likely to invest? Are you reducing investments? Are you shifting more towards Europe? Or is it there is no choice, your largest investments have to be in the US?

We are not scaling back right now because when we look at investments, we look at macro risk environments, but we also look at the individual company dynamism and prospects for growth. And for now, while the risk premiums at the macro level may have increased in America, we still see a lot of leading edge technologies, tremendous dynamism in American enterprises. So we remain invested in these companies. But it’s not America alone. We continue to look out for opportunities around the world, in Europe, and in Asia, and other parts of the world as well.

What about Europe? There is an opportunity for Singapore politically, economically, on the investment front to have a closer relationship with the EU.

We think Europe will be also a key player in this multi-polar environment. Europe is a major power in its own right. And Europe will be a key player in this new global environment, so we are keen to forge closer links with Europe. We already have very close links with Europe between Singapore and the EU, but we are looking at how we can bring different groupings together.

And there are opportunities to do so. Between the CPTPP [Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership] and the EU, for example, we have been having discussions on a more formal partnership that accounts for something like 40 per cent of global trade between EU and Asean. Incidentally, EU has already signed or moved on FTAs, not just with Singapore, but with several Asean member countries. So if we can get EU and Asean together on an FTA discussion, that will be another one third of global trade.

So these we see as new opportunities to reinvigorate trade. I mean, we are in a world where the global system is starting to seem more and more… becoming more and more clogged up. But we would like to keep the arteries of trade open and maybe create new arteries. And that’s why we see these strategic opportunities with Europe.

Does this new world order that is yet to emerge, does it require any domestic changes in Singapore towards more political liberalisation? I ask also because you would have seen that there’s a new youth movement that’s emerging in different parts of the world in Asia and also in Africa, the Gen Z movement. Tell me how you are thinking about the future on domestic social and political liberalisation.

The two are connected, it’s a relevant question, the changes in the global order, as well as the youth movement that you see around the world. And we see growing anxiety amongst young people everywhere in the world. In China, they talk about lying flat. In Japan, there’s a term, hikikomori, staying in the home, not going out. And I think in America, Europe, you talk about the Great Resignation, and all sorts of other terms.

So you see that level of growing anxiety amongst young people. Because we are in a different environment; less stable, more chaotic, more disorderly, so naturally young people are more concerned about their future We feel that in Singapore too. So from a political point of view, from a domestic point of view, our focus must be to find ways to give assurance to our young. To give them that confidence that they can chart a better future for themselves. And that’s what we are determined to do in Singapore.

What’s been the hardest thing that you’ve had to do since you became prime minister?

There are many hard things I don’t know that…

Hardest.

Hardest?

Have you been to see Trump?

Not yet.

OK, so you haven’t done the hardest.

We are. We might have a chance to meet when he comes… if he comes for the Asean summit, which he has said he would.

Yes, yes, because he has to sign the peace agreement.

Yeah. Well, I’m not sure whether it’s just for that, but if it comes to the Asean summits there may be a chance to meet him. I’ve had a phone call with him late last year. It went well. But I’m sure there will be opportunities to meet.

So we take that out. That’s not the hardest. What is the hardest?

The hardest has been really in managing people. You don’t realise the extent of it until you get into this job. Which is that I’m not just prime minister, I’m leading a party. I’m leading a party. I go into elections. And you have to then think about which are the members of my team who I have to drop because I want renewal. And one of the keys to the PAP’s success has been a full focus on renewing our team every election.

And this is not easy to do at all. It’s very easy to say, let’s just continue with the status quo. I don’t want to offend anyone. It’s OK. We all move along. But then if I do less of the renewal, I will pay the price for it 5, 10, 20 years from now. So having to look hard at the members of the team, speak to each one of them individually, and say, I’m sorry, I’m not able to help allow you to continue, I have to drop you, that was very painful.

So party management.

Yes, that was very painful. Not easy to do. And I had to steel myself to do it and manage it. And I’m glad we had a good election outcome at the end of the day.

Thank you for your time and hope to see you again soon.

Thank you. Good talking to you.