Last week was quieter than the preceding weekend’s shortlived eruption in the US-China trade war, though there were a few aftershocks. The annual IMF and World Bank meetings concluded in Washington in a generally fractious and gloomy air, but with a sense of a trade war cataclysm at the least deferred. Today I preview the possible Donald Trump-Xi Jinping meeting later this month and where it will leave the world trading system. I also look at the UK, where a recent spy scandal reveals an economy squeezed between the big three trading powers. Charted Waters, where we look at the data behind world trade, is on the Argentine peso.

Get in touch. Email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

Mutually deferred destruction

If I had to guess I’d say the exchanges last weekend were probably the last proper volleys of artillery before the Trump-Xi meeting, currently scheduled to go ahead (it may still not happen) next week in South Korea. By Tuesday the tension had reduced to Donald Trump taking a feeble stand about American self-sufficiency in cooking oil. On Friday he displayed his continued ineptitude at game theory by saying that his mooted 100 per cent tariffs on China from November 1 were “unsustainable”. (He’s so bad at this.) Any reasonable person (which on this occasion included the equity markets, which rallied a bit) read this as “they’re not going to happen”.

In the meantime, there remains the mild comedy of US officials getting cross and trying to pretend Beijing doesn’t have them on a short leash woven from the finest rare earths. Treasury secretary Scott Bessent was flailing around last week, including in an interview with the FT, blaming China and calling Li Chenggang, its chief negotiator, “unhinged”. Bessent will meet Chinese vice-premier He Lifeng this week to try to smooth the path forward.

Bessent’s ire last week against China looked a lot like projection. The Chinese government, he said, was cutting China off from the world economy, and its trade restrictions reflected anxiety about its economic weakness. Whom does that remind you of? A mystery.

Where are we going to end up? If I had to bet I’d say that in the short term, especially if the meeting happens, there will be a measured relaxation of tension. Trump won’t impose his 100 per cent tariffs and may agree to roll back some of the duties he’s already imposed, or at least extend the moratorium on higher tariffs a second time. China will start buying US soyabeans again, maybe even promise to buy more than before, and will ease off on the rare earth threats.

Beijing is hard-nosed but not wildly self-destructive. It benefits China to be seen as a more trustworthy trading partner than the US, admittedly not currently a particularly onerous challenge. And of course Trump still has some significant retaliatory weapons in software and aviation technology, and retains the ultimate nuclear economic weapon in the form of the dollar payments system.

That leaves the two powers in a situation a bit like an economics and trade version of the cold war. It’s an uneasy peace with each choosing not to inflict maximum damage on the other and in the meantime racing to improve technology and build alliances to gain geoeconomic leverage. It’s not pretty to watch, it’s not necessarily stable and it won’t be great for global growth. But it’s not all-out mutual destruction. Yet.

The UK’s cost of challenging China

If you’ve got a strong view on the British China spying saga you’re a lot better informed than me on the subject, which wouldn’t be hard; or much more opinionated than me in general, which seems improbable.

Whatever the merits of the decisions taken, the UK’s quandaries in taking strong stands against a big investor and trading partner are evident. It’s a smallish economy caught in the economic no-man’s-land between the US, China and the EU, but correctly sees that none of those powers is strong and reliable enough to form an exclusive geoeconomic ally.

The UK’s official “3 Cs” position on China — that it variously has to co-operate, compete and challenge where needed (the last of these especially over national security) is awkward but pragmatic. It’s also very similar to the EU’s watchword that China is “a partner for co-operation, an economic competitor and a systemic rival”.

Over the years the UK has had to make a series of ad-hoc course corrections regarding China. The “golden era” of UK-China relations when David Cameron was prime minister gave way to an abrupt turn in 2020 when the UK, under US pressure, severely restricted Huawei’s access to UK mobile networks. There’s been a growing realisation — and backlash against — Chinese influence in UK universities.

On the other hand, with the government desperate to bring down the cost of living and advance its green goals, and the UK car industry struggling to adapt to electric vehicles, it’s taken an open-market approach to Chinese EVs and declined to follow the EU’s decision to impose stiff anti-subsidy import duties. Chinese EV sales are rocketing in the UK, which is the BYD brand’s second-biggest market after China, despite being in effect excluded from a UK government subsidy scheme.

Steel (it’s always steel) involves tensions with each big trading partner. Earlier this year the UK government had to step in and take control over British Steel from its Chinese owner, Jingye. It demanded 24-hour ministerial access to its plant in Scunthorpe, site of Britain’s last blast furnace, over fears that Jingye would contravene an agreement and shut down production. The US has granted the UK lower steel tariffs than other economies in recognition of political comity or beef import quotas or Trump repeatedly meeting King Charles or whatever, but a promise to cut that tariff to nil appears to have been indefinitely postponed.

Meanwhile, given the size of the respective export markets, the UK faces being clobbered far harder by new EU tariffs on steel, which are due to override the trade deal Britain has with Brussels. Yet as a general proposition there’s not much point saying you’re going to throw in your geoeconomic lot with the EU. Not only does Brussels not have much sentiment even for close trading partners if they’re outside the union but it doesn’t have much more of a clue what to do with Beijing than the UK does.

There’s a vocal China-sceptic lobby in Westminster, and you can absolutely see their argument, but what’s their idea for forestalling the trade and economic punishment that confronting Beijing might provoke? As my FT colleague Stephen Bush says, the guiding principle for the UK’s position on China under Keir Starmer (and his predecessor Rishi Sunak) is essentially “let’s not start something we can’t finish”.

For my part, it’s a while since I’ve used this expression but when it comes to the UK’s quandary with China, I don’t have a solution, but I do admire the problem.

Charted Waters

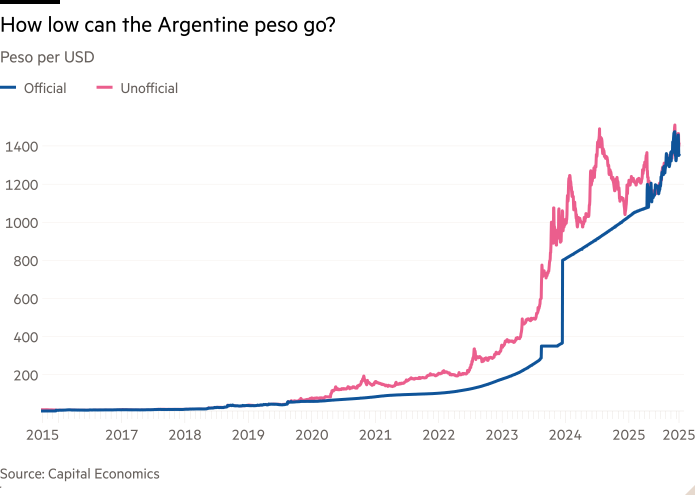

Incredibly, a badly designed politically motivated financial rescue by the US to bail out Trump’s friend Javier Milei (see Trade links below) hasn’t stopped the slide in the Argentine peso.

Trade links

Because the only thing funnier than a plan that isn’t working is a plan twice as big that won’t work, the Trump administration is literally doubling down and increasing its rescue lending to Argentina from $20bn to $40bn. I don’t know why she swallowed a fly, etc.

A deal to restrict carbon emissions from shipping has been blocked at the eleventh hour by the Trump administration, and will now be considered again in a year’s time. For a view from a low-income country, here’s a submission from the Ghanaian chamber of shipping.

The historian and writer Misha Glenny argues that Europe is the big loser in the rare earth wars.

The US is planning to punch further holes in its tariff wall by offering concessions to imports of trucks and truck parts from Mexico and China.

The UK government claims that it will attract more investment from the pharmaceutical industry as a trade-off for increasing the prices it pays for drugs for the National Health Service, a long-standing demand of the pharma lobby.

Trade Secrets is edited by Jonathan Moules