China threatened to retaliate against the UK government if ministers targeted parts of its security apparatus under foreign influence rules, the Guardian can disclose.

Chinese officials warned the Foreign Office that the move would have negative consequences for relations soon after the Guardian reported it was under consideration, according to two government sources with knowledge of the discussions.

The disclosure will raise alarm bells given that ministers have so far refused to apply stricter foreign influence rules on lobbyists acting for China or any part of the Chinese state.

Only Russia and Iran have been included on the enhanced tier of the foreign influence registration scheme (Firs), which was introduced in July and came fully into force this month.

Firs requires anyone in the UK acting for a foreign power or entity to declare their activities to the government or face criminal sanctions. The enhanced tier covers countries and entities deemed a particular risk and requires extra disclosures. As a result, anyone doing undeclared work on behalf of Iran or Russia faces five years in prison.

The Guardian reported in the spring that instead of targeting China as a whole, ministers were considering including specific parts of the Chinese political system that have been accused of interference in the west on the enhanced tier.

Such entities include China’s Ministry of State Security, which is its intelligence service, the Chinese Communist party (CCP), the United Front Work Department, which is often referred to as the international arm of the CCP, and the People’s Liberation Army, which is China’s military.

The government insists that countries’ designations in Firs are kept under review. The Foreign Office was contacted for comment.

Ministers are under pressure over the consequences of their rapprochement with Beijing and are facing questions about the collapse of a trial of two Britons, including a former parliamentary researcher, who were accused of spying for China.

The trial of Christopher Cash, a former parliamentary aide to Conservative MPs Alicia Kearns and Tom Tugendhat, and his friend Christopher Berry had been due to begin this month, but the case was suddenly dropped by the Crown Prosecution Service on 15 September. Cash and Berry denied the charges.

The Sunday Times and the Telegraph reported that the government’s refusal to describe China as an “enemy” in witness evidence from a security official led to the case being abandoned.

Jonathan Powell, the prime minister’s national security adviser, is said to have chaired a meeting in Whitehall last month where he told officials the government’s evidence would stop well short of calling Beijing an enemy.

Whitehall sources denied the claim that Powell was involved in restricting government evidence.

The Sunday Times reported that Powell told the September meeting that additional evidence in the trial expected to be given by Matthew Collins, a deputy national security adviser, would have to be based on Labour’s new national security strategy published this year.

That describes China as a “geo-strategic challenge” and not an enemy. Cash and Berry had been accused of allegedly breaching the 1911 Official Secrets Act, which says that a person is guilty of spying if they pass on information that is “directly or indirectly useful to an enemy”.

Government sources said while the meeting involving Powell had taken place, it had been mischaracterised. They said it would not be possible to insist that Collins cite 2025 government policy when the alleged offences had taken place previously, between 2021 and early 2023, when the Conservatives were in power.

Collins had already given written evidence that had been cited by the CPS in its initial summary of the case in April 2024, at which point the accused were said to have acted in a way “prejudicial to the safety or interests of the UK” by passing on information “directly or indirectly useful to the Chinese state”.

Government sources said that no evidence put forward by the state was withdrawn or changed and that no pressure of any kind was placed on the CPS. Collins’ evidence was considered important because it would help spell out the impact any alleged espionage would have had.

Cash worked as an aide to Kearns, a backbencher, and was accused of passing on information to Berry. The CPS said he in turn wrote up 34 reports, at least some of which were about the British political system, for a Chinese individual assessed to be a member of the country’s intelligence services. The Guardian reported that Cai Qi, China’s fifth most senior official, was believed to be in receipt of this intelligence.

Allies of Cash have indicated that while he did supply information to Berry, it was said to be public material on how parliament or UK politics works – or his personal analyses, such as who he thought would win the next election. Berry’s lawyers were expected to argue that he was working for a corporate client in China looking to expand in the UK.

The CPS has said that the case had been “kept under continuous review” and that it was abandoned because the “evidential standard” was “no longer met”.

On Sunday, officials pointed to a letter from Stephen Parkinson, the director of public prosecutions, who had said in a letter to the shadow home secretary, Chris Philp, that prosecutors had not been subject to “any disclosure or pressure” by politicians in deciding to drop the case ahead of trial.

Shabana Mahmood, the home secretary, told broadcasters that there had been no “ministerial involvement” in the collapse of the case.

Senior Tories have accused the government of collapsing the trial to avoid upsetting China, although the Conservatives also declined to designate the country as a national security threat when they were in power.

In the latest sign of warming relations with Beijing, the Guardian understands that a senior Foreign Office official met Lindsay Hoyle, the Commons speaker, over the summer to discuss the prospect of lifting the ban on the Chinese ambassador entering parliament in return for Beijing lifting its sanctions on UK parliamentarians.

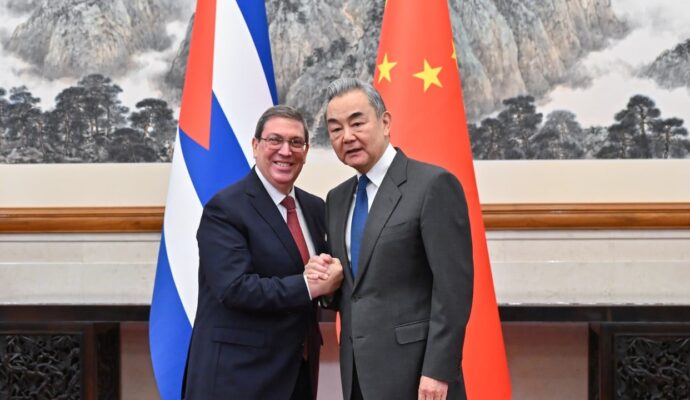

A string of high-level government figures have travelled to China on official visits since Labour came to power, including Peter Kyle, the business secretary, for trade talks last month, and Jonathan Powell, the national security adviser, over the summer.

Keir Starmer is widely expected to make a bilateral trip to China early in the new year, though the timing may depend on Donald Trump, who has said he intends to visit in early 2026.