Good morning. Nandan Nilekani is the co-founder and chair of Infosys Technologies Limited. But for this month’s edition of the India Business Briefing Q&A, I sat down with him at his office in Bengaluru to discuss his other role — as the champion of India Stack, the backbone on which the country’s public digital architecture runs. This includes Aadhaar, the world’s largest biometric identity system, and UPI, the unified payments interface, which hit a record-breaking 20bn transactions last month. We talked about the opportunities and challenges of building technology services that cater to 1.4bn Indians.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity

With Aadhaar, how did you conceive of a product for India when there are so many Indias, in terms of our diverse socio-economic and geographical contexts?

Given India’s vast diversity, our focus was entirely on the minimal rails we could put in, which would apply to everyone and then allow others — the government, the markets, non-profits — to build specific contextual solutions for different categories. That’s why we call this digital “public” infrastructure. When we solve the problem of identity or that of payments, it’s not about a particular use case, but allowing different people to use it in different contexts.

One criticism has been that Aadhaar is difficult for people who cannot afford its basic requirements of access to technology and personal paperwork.

When we design population-scale digital infrastructure, inclusion is a huge driver and not an afterthought. The inclusion goes to the extent that when we issue the IDs, even, say, homeless people can apply for it giving the address of a shelter, for example. If people didn’t have a birth certificate, they could have a birth date assigned to them. So there were a lot of very specific things done to make it massively inclusive.

My own experience with Aadhaar is that it is significantly tied to the mobile phone and one-time passwords . . .

Yes, you do need a password for some kinds of transactions. But let’s say you want to withdraw money from your bank account, which is a huge use case in villages. Earlier, people had to go a long way to the local district headquarters to a bank branch, where they were not treated well because they were poor. That has entirely changed because we now have a network of “business correspondents” who are dedicated people armed with devices. Users can take their Aadhaar card [to these correspondents], do a face authentication, and this allows them to withdraw money from their account. This system does 100mn transactions a month. There’s no phone involved.

Aadhaar and the unified payment system, UPI, are part of the fabric of our lives now. Are there other products on the India stack that have taken off in a similar manner?

Most of these things have a long gestation period and lead time. These are not private sector initiatives, where a company can just decide and launch a product. It is a much more amorphous situation when it’s for a public good, several stakeholders are involved — government, regulators, markets etc. We have to navigate all of that and it takes time to get the right fit.

One of the early things I was involved with was Fast Tag (which allows electronic payment of road tolls). When Kamal Nath was the roads minister, he asked me to come up with a simpler way of tolling and I worked on a report for the ministry. That was 2010! Today, it has become universal and ubiquitous, with billions of transactions. And it’s designed to go beyond tolling. Many start-ups are now using it for parking solutions, and a future use case could be congestion charges. That’s an example of something that took a long time but which has grown substantially in the past few years.

What about ONDC, the open platform for digital commerce? That’s one segment in which the private sector is far ahead.

I think they are really picking up, they are doing 15-16mn transactions a month. I think in the next year or so, it will grow substantially. ONDC covers a wide variety of transaction types: physical transactions, ecommerce, mobility solutions and financial transactions. I think as these categories grow more, that will become another important and vital infrastructure for enabling commerce in India through an open architecture. ONDC is only four years old, it has a great future.

Another big product is the account aggregator, which also does a lot of transactions, and enables credit by easily giving access to verify your bank account or personal finance applications for mutual fund investments and such like. It’s at a huge take-off point now. It was conceived and launched by the Reserve Bank of India nine years ago. The point is that these public systems take time, but suddenly, when everything falls into place, they hit a take-off point. That can be an external event such as Covid, which was a big tailwind for digital payments. For Aadhaar, it was the government’s Jan Dhan financial inclusion push.

My biggest mistake

Standing for election in 2014. The reality was that I was not good at it and I was not suitable for it. It was an act of hubris. Because I had been successful at Infosys, and at implementing Aadhaar etc, I thought I’d be successful at anything I tried. No, that was a mistake for sure.

Tech start-ups tell me they worry about building something of scale, only to have the government come in with a similar product. A case in point is the bills payment mechanism, which was the domain of start-ups and is now mostly the government’s. How do you respond to that?

Well, you have to look at what is in the public interest. Public interest is how to get a billion people have access to something. That will mean that some things will have to be open rails. That’s the nature of the beast. That’s the risk you take in business.

Are you satisfied with the number and nature of projects that private companies are building on the rails? Do you see enough interest?

If you look at the market value of companies created on top of the digital public infrastructure of India, it would be in excess of $100bn-$150bn. These are companies that didn’t exist 10 years back, and have now become formidable players. PhonePe is an example, I think they last raised money at a valuation of $12bn or thereabouts. Now they’re going public. Similarly, Razorpay has built a large B2B business and Groww has built a large discount broking, wealth management company. Each of these companies have multibillion-dollar valuations.

So what are you building next?

I am working on AI, and how to apply the technology for education, agriculture and languages. On the language side, I’ve been supporting an initiative at IIT Madras called AI for Bharat. They are building the world’s largest dataset for Indian languages, which they are sharing publicly. For example, the government is using it in its language initiative Bhashini. There is a repository that has now come out called AIKosh, which is a public dataset that anyone can use. The idea is that we can accelerate AI access for Indian languages, and that will have a huge multiplier effect.

By that do you mean access AI in a regional Indian language?

Yes. If you go back to the world of PCs, you had to have English and you had to have a keyboard. Smartphones made that simpler with touchscreens and videos. But if you really want ubiquitous, universal access to computing, it should be in a language of your choice, whether it is Hindi or Bhojpuri or Maithili, and the technology should understand you. This initiative will accelerate over the next few years, and it will dramatically increase access to computing.

That’s language. What about education?

We are looking at how to improve basic literacy and numeracy. India has seen only marginal improvement on this in the last 20 years. We are trying to create a model called AXL — AI for learning, numeracy and literacy, which can be used in the school system. (Essentially, a teacher supported, AI-powered system that helps children learn and keep up with their peers). Several states are now rolling it out. We think that over the next few years, this will help in improving foundational learning of children, which is a huge requirement in India.

And on agriculture?

India has a large base of farmers. If there’s a way we can give them access to the latest data and knowledge in their own language, then we can create something quite big. That initiative is called the open agri-network. Recently Maharashtra launched a version of this, called Mahavistaar, which is using this infrastructure. National Payments Corporation (which manages UPI) is going to launch payments in Indian languages where you can speak to the phone and make a payment in Hindi or Tamil or whatever.

Agriculture, education and language are all big areas and all of them have one common thing. They are universal, they apply to a billion Indians and they have huge economic, social and productivity benefits. When we examine where we want to work, we look at areas where the impact can be quite large.

I also wanted to get your views on data privacy and the increasing amount of financial fraud. What needs to be done?

India now has a digital personal data protection act, which provides a framework for data privacy and I think that obviously has to be enforced. That’s one part. A lot of the financial fraud, which is happening, is behaviour-led fraud. It’s not technical fraud. It’s because more than half a billion people were brought into the formal financial system and they are not all aware of the risks.

But if you have brought less technology savvy individuals into a digital existence, you do have to ensure their interests are protected, don’t you?

Yes, but those are separate issues — how do we improve financial literacy and how do we educate people on how not to be defrauded. Digital security is always a race between fraudsters and users. But I think certainly massive financial inclusion and awareness should be something the government can do.

Is that something you are discussing with the government?

No, I’m not involved with that. I mean, there are certain things I do and many things I don’t do.

After hours

I am reading Chip War by Chris Miller. It’s very good. I don’t read many new books. I’m reading a book on the spice wars of the 16th century. One thing I find is that if you go back and read something from 500 years ago, it puts the present in perspective too: You begin to think, “what’s the big deal, this is also just another phase”.

Recommended stories

Donald Trump announces 100 per cent tariff on branded pharmaceutical products.

Naveen Jindal: India’s polo-playing steel tycoon behind the bid for Thyssenkrupp’s steel unit.

Steel magnate Sanjeev Gupta has sold his Dubai mansion as his business woes mount.

Jaguar Land Rover will bear the full cost of a cyber attack due to lack of insurance cover.

Accenture to ‘exit’ staff who cannot be retrained for age of AI.

Inside the billion-dollar quest to live beyond 100.

Why do bad guys look so good?

Buzzer round

Which Indian company is in the world’s top three applicants for America’s H-1B visas? (Hint — even though this edition of the newsletter features Nandan Nilekani, the answer is not Infosys)

Send your answer to indiabrief@ft.com and check Tuesday’s newsletter to see if you were the first one to get it right.

Quick answer

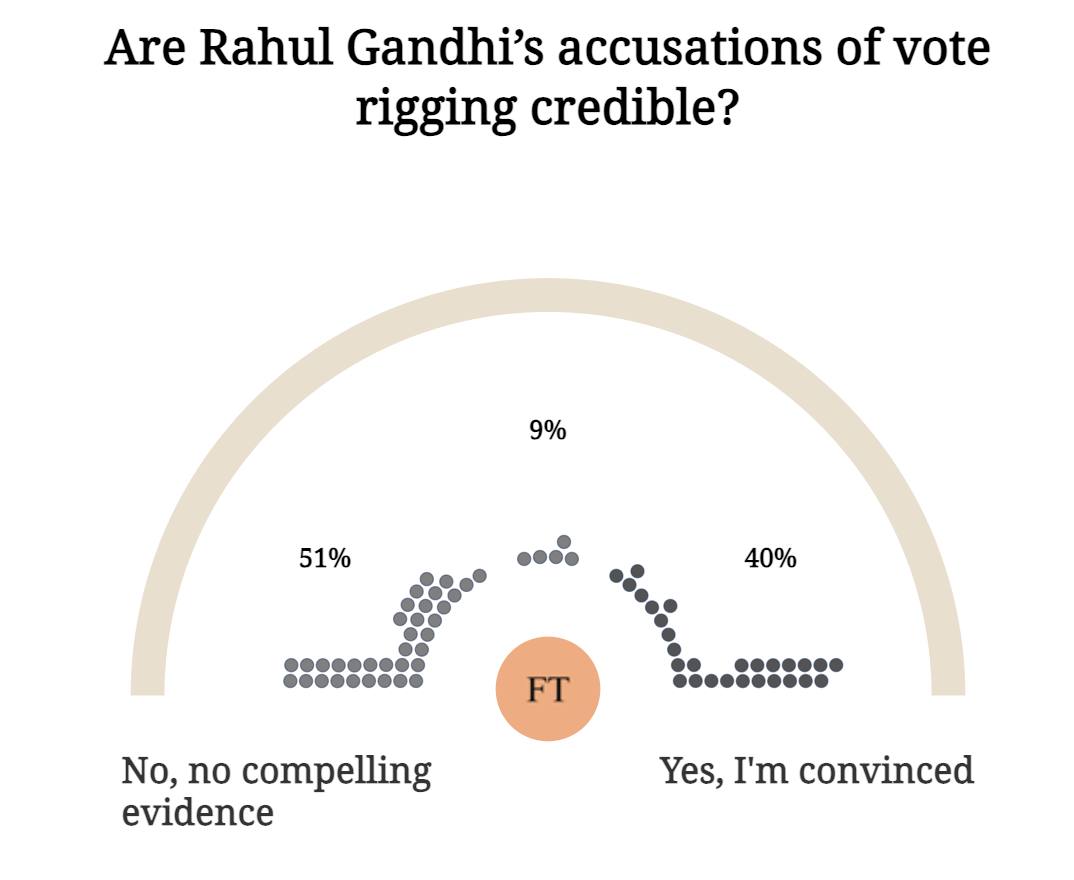

On Tuesday we asked if you thought Rahul Gandhi’s accusations of vote rigging were credible. It’s a close result, with 51 per cent of you leaning towards no.

Thank you for reading. India Business Briefing is edited by Tee Zhuo. Please send feedback, suggestions (and gossip) to indiabrief@ft.com.