On India’s polo fields, Naveen Jindal is not just a billionaire patron of the sport. To his teammates, the chair of Jindal Steel is “Captain Cool”, as well as a sharpshooter casting himself as a “sporting chief, commanding the field with precision and pride”.

Off field, the flamboyant 55-year-old tycoon is making equally grand plays in business. Last week, Jindal made an offer for the floundering steel assets of German industrial group Thyssenkrupp.

The bid value was undisclosed but Jindal pledged to invest more than €2bn and put himself in direct competition with Czech billionaire Daniel Křetínský, who last year acquired a 20 per cent stake with the potential to buy another 30 per cent.

A successful takeover would vault Jindal, who owns India’s fourth-largest steel producer, into the world’s leading makers of the metal, with sprawling, but integrated assets that include mines in Africa and Australia, as well as steel plants in Oman and Europe. It would also mark his second major acquisition in the region.

Late last year, Jindal acquired Vítkovice Steel, an 800,000-tonne-per-year manufacturer in the Czech Republic. He has promised to invest up to €150mn in the facility, boosting its capabilities in areas such as rolled sheet capacity. Jindal has previously been in talks with Rome to buy a distressed steel plant formerly known as Ilva near Taranto in southern Italy.

“Jindal Group has been expanding their global footprint,” said Rajesh Ravi, an analyst at HDFC Securities in Mumbai. “In India they are already a significant player — they are trying to become a formidable player in the European Union.”

Jindal’s group, which spans steel to coal to cement, generated about €12bn in revenue with a 22 per cent earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation margin in the financial year ending in March. Naveen Jindal and related parties own about 62 per cent of Mumbai-listed Jindal Steel.

The tycoon’s company has “a lot of cash on their books”, said Alok Deora at Mumbai-based financial services group Motilal Oswal. “Companies are hunting for assets in India as well as globally,” he added.

Yet analysts warn that Jindal’s European push comes amid low demand across markets, cheap imports, and high energy costs. Thyssenkrupp blamed “persistently weak demand and lower price levels” as sales for the three months to June fell 13 per cent from a year before to €2.5bn while its adjusted earnings before interest and tax plunged 69 per cent to €31mn from the previous year.

“Thyssenkrupp’s pension liability is also huge,” warned another industry expert, with any bidder for the steel division having to reckon with pension liabilities of about €2.7bn.

However, the purchase of the German group will bring its benefits. Colin Richardson, steel analyst at Argus Media, said much of the market was “unsurprised by Jindal’s bid,” since Thyssenkrupp’s steel unit was set to gain from an increase in European defence spending.

The acquisition will also help in the face of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which will impose levies on high-emission imports such as steel. The emissions levies to be brought in from next year threaten the competitiveness of Indian exporters, many of which use dirty, coking coal-fuelled blast furnaces.

About two-thirds of India’s 9mn metric tons of steel shipments go to Europe. “CBAM will definitely impact” those exports, Sandeep Poundrik, steel secretary in India’s government, told the FT Live’s Energy Transition Summit India last week. However, greener plants inside Europe will help Jindal shield his group from these barriers, said analysts.

Thyssenkrupp’s workers are hopeful about Jindal’s approach. Tekin Nasikkol, head of the works council at Thyssenkrupp Steel Europe, received a letter from the Jindal family, stressing the importance of having employee representation at board level — a pillar of Germany’s corporate culture.

The Indian side’s proposal of an “open and constructive dialogue” was well received by the works council in Duisburg, with Nasikkol noting: “We accept this offer.”

Boldness runs in the family. Jindal’s father, Om Prakash Jindal, was regarded as a pioneer in India’s steel sector before dying in a helicopter crash in 2005.

In the late 1990s, the elder Jindal divided his business empire among his four sons, while his widow Savitri became chair of the holding company to ensure unity. Naveen’s older half-brother Sajjan built JSW Group into India’s largest steelmaker, creating a dynastic rivalry between the siblings.

Naveen Jindal’s appetite for international adventure is not new. His listed Indian company signed an agreement to invest $2.1bn in a Bolivian mining and steel project in 2007. He eventually pulled the plug on the project following frictions with Bolivia’s leftist government, but analysts praised his efforts to deleverage the Indian business and make it into a credible global player.

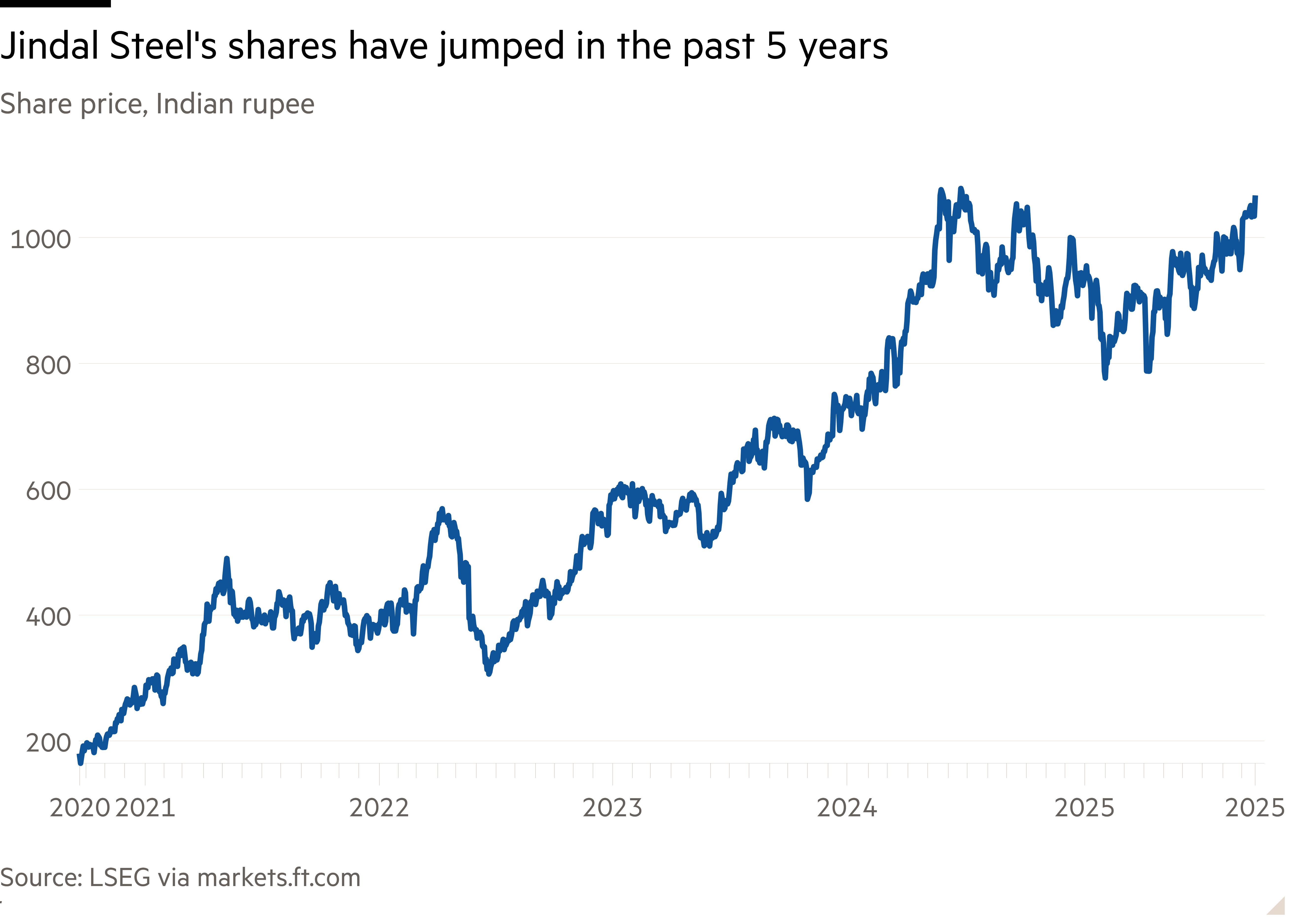

“Naveen Jindal has been credited with turning around Jindal Steel. It has grown significantly,” said Ravi at HDFC Securities. The Indian company’s shares have risen more than fivefold over the past five years.

His passion for elite sports has shaped his glamorous image, while a near decade-long legal battle to lift government restrictions on flying the Indian national flag has reinforced his patriotic reputation. In 2004, India’s Supreme Court overturned the rules, establishing the right of all citizens to display the flag.

That same year he followed his father’s footsteps in becoming an elected member of the Indian parliament’s lower house. The steel chief represents Kurukshetra, a predominately rural north Indian constituency and the site of a mythological battle in the ancient Hindu epic the Mahabharata.

However, more than a decade ago, Naveen Jindal’s business was dragged into an Indian police investigation over coal mining rights, dubbed the “coalgate” scandal. He has repeatedly denied any wrongdoing.

On the campaign trail, the billionaire has sought to project himself as a man of the people. “People know if they need Naveen, they can catch hold of Naveen,” he told the Financial Times ahead of the 2014 election, which he lost.

Naveen Jindal and Jindal Steel did not respond to requests for comment or an interview.

Last year, he joined Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata party, switching from the beleaguered opposition Congress party and winning back his seat. The person familiar with the tycoon said he was “moving away from a sinking boat”.

At the time, Congress’ chief spokesperson, Jairam Ramesh, hit out against Jindal. “When you need a giant-size washing machine, this had to happen,” he said in reference to the coal investigations. The steel chief has said his move was motivated by a desire to contribute to Modi’s development goals.

For now, his focus is on the European steel chessboard. If he succeeds, the polo-playing Captain Cool could ride into a new league of global steel barons.

Additional reporting by Gillian Plimmer in London, Andres Schipani in Jaipur and Raphael Minder in Warsaw