This article is part of FT Globetrotter’s guide to Tokyo

The origin story for many great chefs tends to start at home, with a love of food instilled from an early age through a diet of mum’s faultless cooking, picking vegetables with grandparents or kitchen time with a chef dad. Daniel Calvert is different. Food wasn’t central to family life when he was growing up in Surrey in the nineties and noughties. Yet by the time he was a young teenager he knew he wanted to be a chef — and work in the world’s top restaurants. “I still have no idea where it came from,” he says.

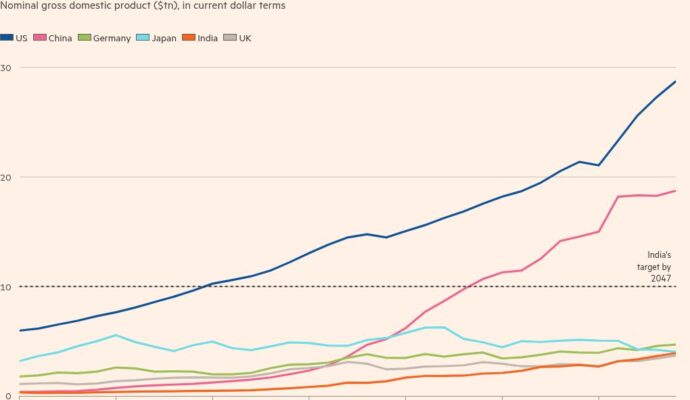

The kid with conviction has since worked his way up through some of the most acclaimed kitchens from London to New York, Paris and Hong Kong, and now Calvert is rapidly creating a class of his own at Sézanne, his restaurant in the Four Seasons Marunouchi in Tokyo. Since opening in 2021, Sézanne has emerged as a dining destination for top chefs and gourmands alike, for a menu that weaves together French technique and Japanese ingredients with Calvert’s uniquely global insight. It was awarded three Michelin stars in October last year — one of only 12 restaurants with the accolade in Tokyo, a city with the greatest number worldwide — and the waiting list for a table can stretch to eight weeks.

We are visiting Sézanne, a light-drenched 30-seat dining room overlooking Tokyo Station, for an autumn lunch, when the temperature in the capital is cooling and some of Japan’s most prized — and fleeting — produce is in season: soft-shell turtle, seiko gani (a native female snow crab) and jellyfish, to name a few ingredients that I am intrigued to ingest for the first time.

Sézanne’s typically 12-course menu is around 70 per cent seafood, hyper-seasonal and therefore frequently changes (“I also get bored quickly,” Calvert says). It is entirely a surprise to diners, though we are provided with a note listing the restaurant’s suppliers, a nod to the particularly direct relationship between chefs in Japan and purveyors.

In the early hours before heading to the restaurant, three times per week, Calvert, who is personable and low-key, visits his sources at the Toyosu fish market. “Some [relationships] have existed for 100 years and the suppliers don’t care about who you are and your money,” he says. “They choose who they want to work with too.” All of the ingredients used in the restaurant, except for a small number of products such as truffles, caviar and foie gras, are Japanese.

Lunch begins in charted territory with a comté gougère (the platonic ideal of a cheesy choux bun) before our western palates dive into the lesser trodden. The soft-shell turtle arrives in the form of soup: it’s frothy and viscous, meaty but delicate, with umami and an inherent sweetness (it reminds me of frogs’ legs). The dish reflects Calvert’s east-meets-west sensibility: it is inspired by a blanquette (a French stew usually cooked with veal) but offers the characteristics of both Japanese suppon (turtle soup) and velouté.

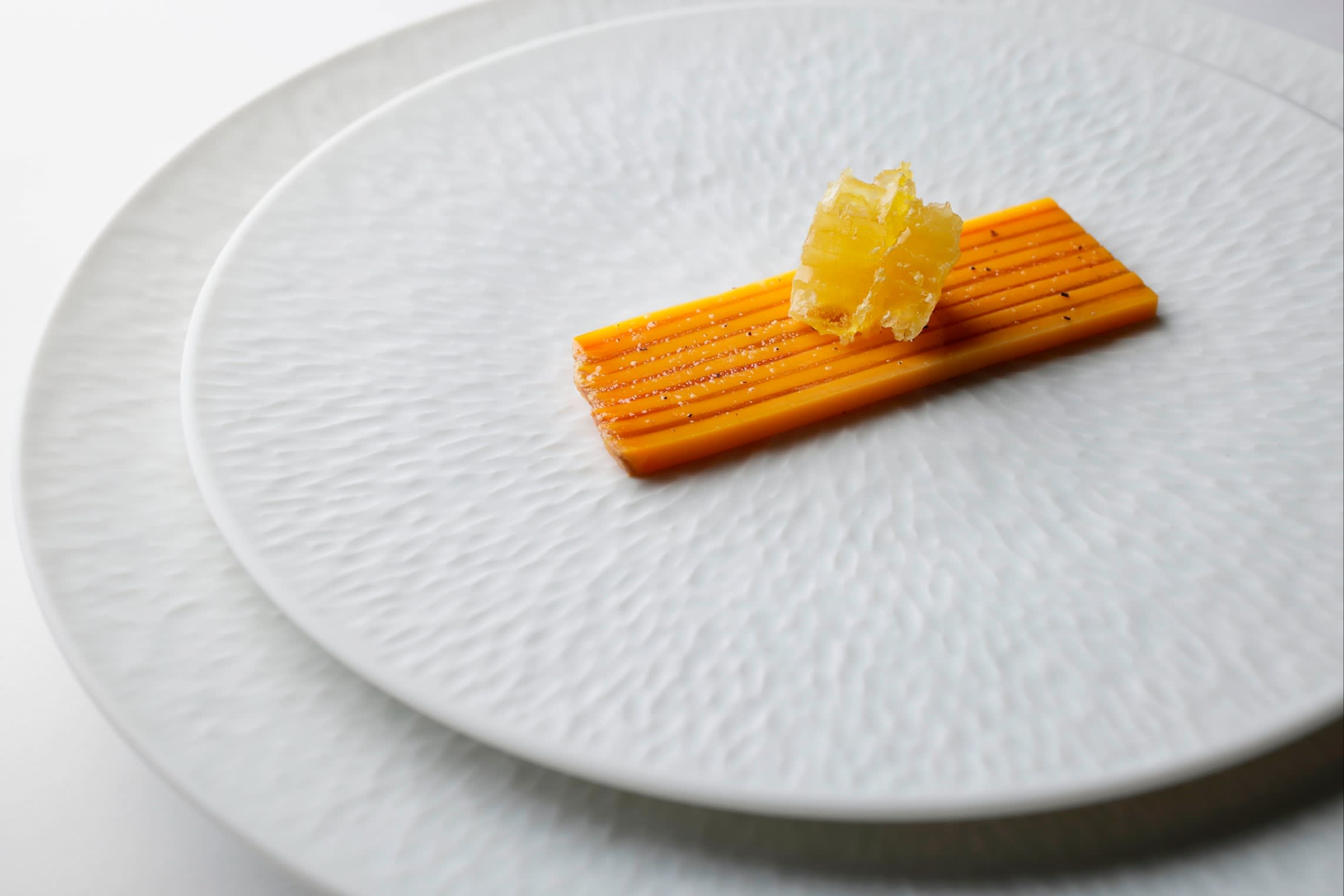

Skilful precision is displayed on every plate, as a geometrically exact stack of puff pastry, topped with layers of cured Japanese mackerel, is followed by a caviar tart, its basket gossamer-thin, crowned with a roundel of avocado and lime zest. The flavours are light and clean, yet complex, slightly smoky and wonderfully harmonious. There is a fillet of amadai, a native fish similar to bream, which has had its scales carefully detached, fried in hot clarified butter (a Japanese and Chinese culinary technique), and reapplied upright, like a slew of Sydney opera houses bunched together, weightless and crisp. “It’s a bit like popcorn,” Calvert says with a smile.

It is jellyfish, however, that comes as a great surprise: sliced ultra-thin like spaghetti, and crunchy and vegetal, it is more like eating a radish than a sea creature. With tomatoes, anchovies and a tuna milk dressing, the dish offers the flavours of a Niçoise salad.

“The produce here is excellent but it’s different, and it reacts differently to western cooking, so we had to learn how to use it,” Calvert says of himself and his Sheffield-born executive sous chef Ashley Caley. “I’m quite tired of French food, to be honest. I’ve been doing it for 20 years. So all these ingredients that we’re using here . . . we’re trying to explore other things.”

At 16, Calvert, a Woking native, left school for London, first landing as a line cook at The Ivy and eventually the two-star kitchen of the revered Pied à Terre, working under Australian chef Shane Osborn and learning the fundamentals of French culinary technique. His CV in the years since grew to read like pages on a gastronomic passport: Per Se in New York City, Epicure at Le Bristol in Paris and, most recently, Belon, a neo-Parisian bistro in Hong Kong, where as head chef he led the restaurant to its first Michelin star and the upper echelons of Asia’s 50 Best list, firmly establishing himself as one of the most adroit chefs in the region. Then Tokyo came calling.

“I didn’t want to leave [Hong Kong], but this opportunity came up and I couldn’t turn it down,” he says. “If you can make it in Tokyo, you can make it everywhere.”

When Calvert and the Four Seasons joined forces in the Japanese capital, the goal of the partnership was simple: “The stipulation was that we would win two Michelin stars,” he says.

Calvert appears to have made light work of the task. In 2022, less than six months after opening, Sézanne was awarded a Michelin star, with the second clinched shortly after in 2023. Late last year, it was bestowed a third — an accolade held by only 157 venues on the planet and an accomplishment that had never been managed before by a British chef outside of the UK. (He is, by the way, only 37 years old.)

Meanwhile, Sézanne has consistently tracked in the top slots of the 50 Best lists, named the Best Restaurant in Asia in 2024, and is currently ranked number seven in the world. Sommelier Nobuhide Otsuka’s drinks programme is also award-winning, with an extensive cellar of champagne (the restaurant is named after the Côte de Sézanne), wine and sake, and the pairing we enjoy with lunch is nothing short of spectacular (it starts with an intention-setting glass of Krug cuvée).

As a result Sézanne is emerging as a point of pilgrimage for the world’s top chefs: Clare Smyth, Julien Royer, Jean-Georges Vongerichten and Australian seafood pioneer Josh Niland are just some of the food world’s famous faces known to have recently dined at the restaurant. It holds a waiting list of chefs who want to work there; some spend their holiday time gaining experience in Sézanne’s kitchen.

“It’s like what [chef Massimo] Bottura’s restaurant used to be,” a contact tells me, pointing to Osteria Francescana in Modena, the influential three-star restaurant that was twice named the world’s number one.

Diners too, of course, descend on Sézanne from around the globe to experience Calvert’s cookery, of which they can catch glimpses through a large glass window that displays the kitchen. When we lunch, some of the other guests seem to be dining on business, or are otherwise well-heeled international tourists and Tokyo locals savouring the menu and refined yet enthusiastic service. Calvert prides himself on the number of regular guests Sézanne has. “We get repeat customers once a month or once every six weeks,” he says. “It’s the most important business.”

Bottom line aside, there are other secrets to his success. Calvert seems relentlessly hardworking, indefatigable and is clearly talented, but it’s curiosity and collaboration that he points to as key.

“I ask questions . . . I talk to a lot of chefs,” he says. “If I go out for sushi, for example, I ask what fish they’re using, where it’s from, how long do you cure it for, that kind of stuff.”

There’s also plenty of trial and error, particularly when working with new ingredients. When Calvert first spotted soft-shell turtle at the fish market, for example, he asked the Japanese chefs at Sézanne to teach him the traditional method of cooking it, then made the dish for himself. After that, “I work out how I want to cook something,” he says. “But you have to start somewhere . . . as a chef, you should never stop learning.”

Menu Sézanne, ¥50,600 (£252/$344), lunch and dinner

Sézanne at Four Seasons Hotel Tokyo at Marunouchi, 1-11-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-6277. Opening times: lunch, Wednesday-Saturday, noon-1.30pm (last seating); dinner, Wednesday-Sunday, 6pm-8pm (last seating). Website; Directions

Off-duty: Daniel Calvert’s top Tokyo eats

Amamoto. It’s not so easily bookable, but it is one of the best places for sushi in Tokyo. The chef’s dishes are always very original. There are certain dishes you will only ever have if you go to Amamoto. I like his hay-smoked bonito; his sashimi is also very good. It changes every time we go. His tamago (egg pudding) is beautiful.

Hatou — it’s in Kagurazaka, which is my neighbourhood. The chef here, Daichi Kumakiri, trained at Amamoto, and before he was a sushi chef he trained at a kaiseki restaurant, so all of his small dishes are very elegant and kaiseki-esque. His nigiri is also very, very good.

Kagari, in Ginza. The most common ramen is pork-based, but this is chicken-based, which I like because it’s a bit lighter. Kagari boils its chicken broth for hours so the fat sort of re-emulsifies into itself, which is super-rich and delicious.

Pizza Studio Tamaki. Go right when it opens at five o’clock, otherwise you’ll have to wait for a long time. It’s all wood-fired. When dusting the board, the chef puts a little bit of salt in the semolina flour, so you can get a bit of salt on the tip of your tongue when you’re eating the pizza. It’s the best pizza outside of Italy.

Tokyo Confidential — a cocktail bar in Azabu-Juban, run by a friend of mine, Holly Graham, from London. She was in Hong Kong and Korea for many years, so she’s been in Asia for a long time. It has a balcony and a rooftop, an incredible view of Tokyo Tower — and she makes beautiful drinks. I also, of course, like Virtù, the award-winning cocktail bar at the Four Seasons Otemachi. And Bar Trench — it’s very small, with only three or so tables plus seats at the bar. There’s also The SG Club in Shibuya. They have three different floors — I like the one downstairs best.

Niki Blasina is Fortnum & Mason’s Restaurant Writer of the Year 2025

Have you dined at Sézanne? Share your experience in the comments below. And follow FT Globetrotter on Instagram at @FTGlobetrotter