Welcome back. In late August, US President Donald Trump raised his already high duties on India to 50 per cent as punishment for the country’s purchases of Russian oil. That made it one of the world’s most heavily tariffed countries by the US.

As America is also India’s single largest export market for products, many fear the worst for the country’s economic prospects. This week, however, I lay out the argument for why the world’s most populous nation can endure the US president’s tariff blitz — and how it might even prosper because of it.

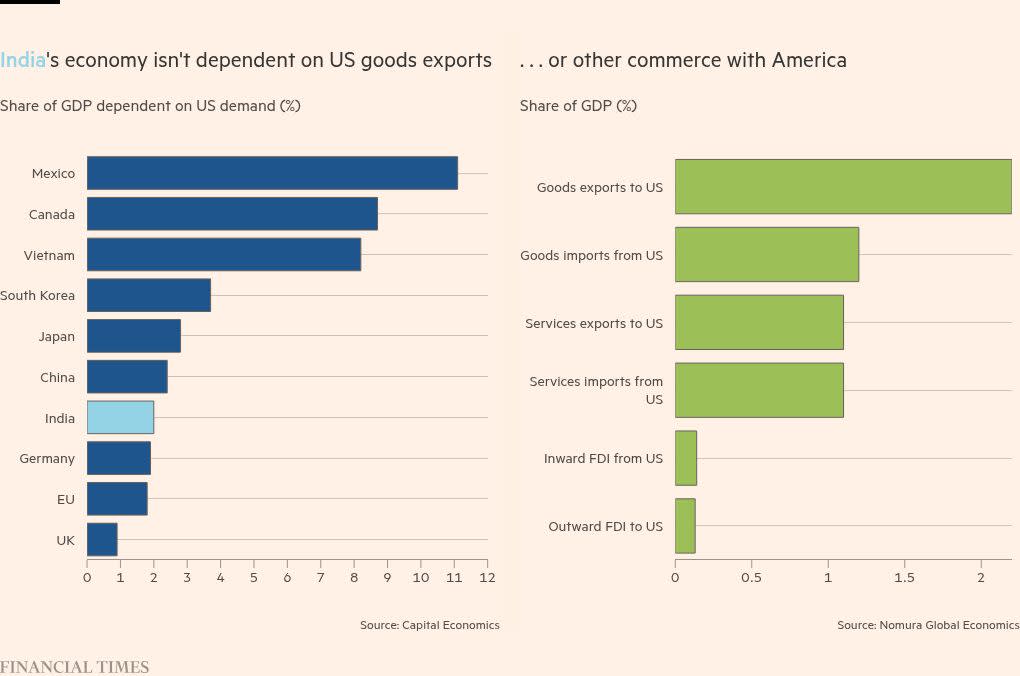

First, the high US tariff rate on India isn’t as bad as it looks. Although one-fifth of the country’s product exports go to the US, India is not a major goods producer.

In fact, Capital Economics estimates that US goods demand drives just 2 per cent of India’s GDP.

Also, 30 per cent of India’s goods exports to America — including in major sectors such as consumer electronics and pharmaceuticals — have been carved out of Trump’s tariffs, according to FT analysis.

That means the US’s effective tariff rate on Indian goods is estimated to be within a slightly less alarming, but still high, range of 33 to 36 per cent, just behind China and Brazil.

Still, economists estimate a significant 0.6 to 0.8 percentage point hit to India’s annual growth rate because of the duties. (At a revised projected rate of between 6 and 7 per cent, it will still be the world’s fastest growing major economy.)

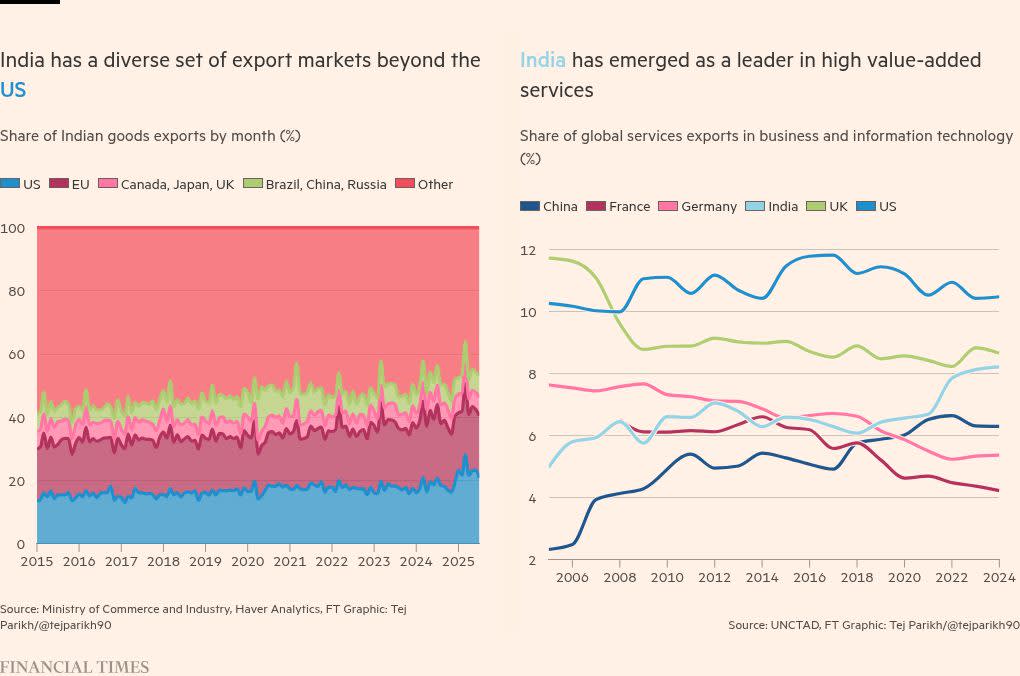

As the FT reported last week, some of the worst-affected industries — for example, textiles, gems, jewellery and carpets — are also some of India’s biggest employers. But the country can expand into other markets and make mitigations.

The bearish emphasis on the US being India’s largest individual export destination overlooks that India sent more goods to EU nations as a bloc than to America last year. Also, relative to international standards India has diverse trade relations, reflected in its low export market concentration score.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has expedited negotiations with other international partners since Trump laid down his punitive duties. Following talks earlier this month, India and the EU appear on track to meet a year-end deadline for a free trade agreement. Modi has also boosted economic ties with China and Japan in recent weeks.

“Export diversification is a good medium-term strategy. Fast-tracking trade negotiations means businesses can refocus supply chains on Europe, the Gulf nations, Latin America and closer to home across Asia,” says Sonal Varma, India chief economist at Nomura. “In the near term, exporters will also cut prices to try retaining US market share. A touted support package for affected companies may help too.”

Second, India’s strength in high value-added services positions it to benefit from secular growth trends that are largely resilient to — and far outweigh — the impact of Trump’s tariffs.

Over the past two decades, India has shifted from housing multinationals’ back-office functions to their “global capability centres” (GCCs), where more lucrative activities — including research and development, data analysis and coding — are conducted. The country’s share of global business and IT services exports is now on par with the UK, and closing in on the US.

The number of GCCs is forecast to rise by 700 to 2,400 by 2030. Dun & Bradstreet projects their direct contribution to output to double to $143bn in that period. NASSCOM, a trade association, estimates tech industry revenues could more than double to $500bn by 2030.

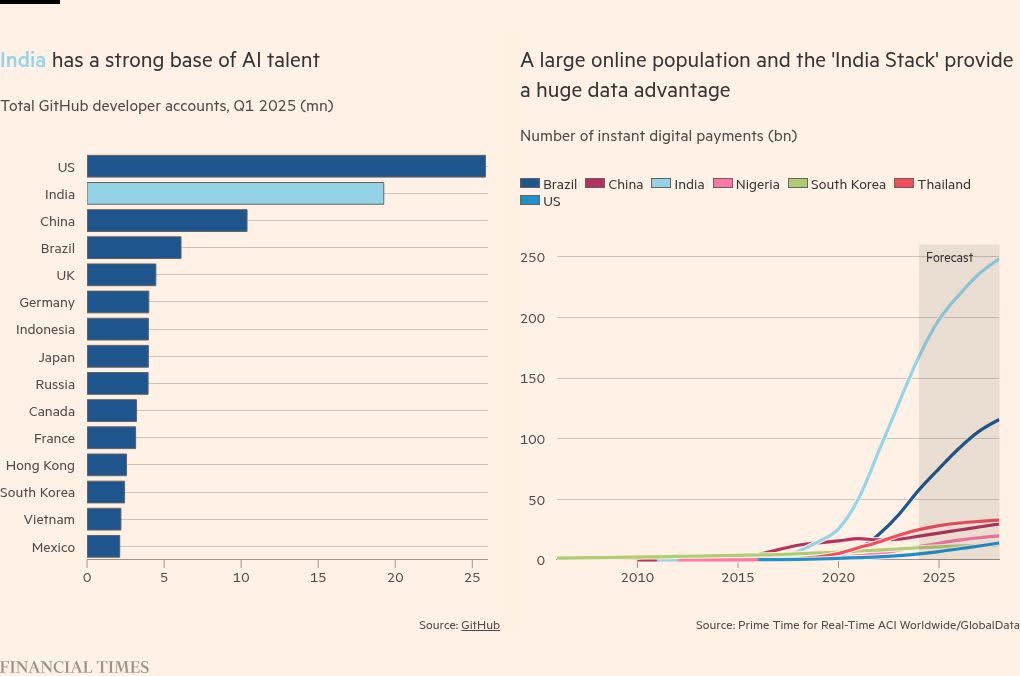

Artificial intelligence might lead to automation of some activities. But India’s large pool of Stem skills and the country’s shift up the value chain mean it will most likely be a net beneficiary of the technology.

“Global firms should be keen to capitalise on India’s low employment costs, talent and expertise to support their own AI deployment,” says Rohit Goel, head of global macro research at Breakout Capital. Indeed, it has the world’s second-largest number of developers on coding platform GitHub. Patenting activity, including in AI, has grown fast too, according to analysis by BCA Research.

A large online population, the “India Stack” — a national digital platform for biometric identification and payments — and openness to foreign tech firms make the country ideal for model testing, product scaling and adoption.

EY estimates that generative AI could cumulatively add up to $1.5tn to India’s GDP by 2030.

For measure, the Indian government estimates that Trump’s tariffs will impact $48.2bn of exports.

Third, India’s large domestic market can help defray much of the immediate hit from tariffs.

Although India’s “consuming class” is estimated to be about 10 per cent of its population by venture capital company Blume Ventures, that’s still around 140mn people. The firm classifies a further 300mn as “emerging consumers”.

As inflation has fallen, that large consumer base has become more confident. Policy measures could help “buoy household consumption”, adds Tanvee Gupta Jain, chief India economist at UBS Securities India.

Modi has already pledged cuts and a simplification to the goods and services tax. The Reserve Bank of India is also expected to frontload interest rate cuts to offset the economic hit of the duties.

“Various government and monetary policy measures could largely offset downside risks to growth in the coming quarters,” says Gupta Jain. “But their support will wane if high tariffs linger.”

Finally, Trump’s tariffs might push India towards deeper structural reforms.

“This kind of external shock can galvanise people and politicians into making long-term economic improvements,” says Breakout Capital’s Goel. Indeed, in India, a balance-of-payments crisis triggered major economic liberalisation efforts in the early 1990s.

Today, striking meaningful trade deals will probably require India to lower its own tariff barriers. That would have the added benefit of opening up coddled industries to competition.

As I outlined in the May 11 edition of this newsletter, internal trade hurdles — including high logistics costs and a plethora of burdensome regulations — worsen India’s export competitiveness (even before considering any external duties) and hinder scaling.

Streamlining labour market regulations, improving access to land, reducing the compliance burden on companies and investing in upskilling initiatives would be most impactful. (Encouraging competition between India’s diverse states could provide the impetus.)

Any further progress on these reforms would bolster the growth trajectory of India’s high-end services industry and, by raising incomes, boost the domestic consumer market too. It would also help more labour-intensive goods-producing sectors expand, just as multinational companies are diversifying their supply chains. Together, these measures would add to India’s growth potential far more than Trump’s tariffs would diminish it.

Sluggish reform efforts and, of course, Trump are big risks to this optimistic take.

The US president could extend threats to India’s services sector. But since America’s Big Tech companies benefit from GCCs and open access to India’s vast digital market, he may not bite.

And, though Trump could add further tariffs on goods, there has been some progress in negotiations between the two nations in the past week. The Indian government’s chief economic adviser is hopeful the punitive rate might be withdrawn “after November”.

Either way, US duties should be a wake-up call for the country. Even if Trump reduces his levies, India still faces high “reciprocal” tariffs. Motives to improve ties with other trade partners and enact reforms will remain for the duration of the mercurial Trump presidency.

In any case, trade diversification and supply-side measures will pay dividends if a future US administration does decide to roll back the tariff barriers.

In sum, Trump’s tariffs on India may seem severe. But beyond the headlines, at worst they may be but a blip in India’s broader growth story. And at best, they could be a catalyst.

Too bullish, or fair assessment? Send your thoughts to freelunch@ft.com or on X @tejparikh90.

Food for thought

What can public health policy learn from the long lifespans of kings and queens? After analysing royal longevity from the 17th century until today, this study has some answers.

Free Lunch on Sunday is edited by Harvey Nriapia