When, after almost six weeks of confinement in hospital, Linda Mangan was told she could continue her recovery from a debilitating stroke at home, it felt “like winning the lottery”.

Thanks to a team of physiotherapists and occupational therapists employed by Ireland’s Health Service Executive who visited her over the course of two months, the 61-year-old retired factory supervisor from Cork has turned a corner.

“[I can] make sandwiches, wash my hair, I can shower myself”, despite initially having lost all movement in one arm, she said.

Mangan’s return to strength is emblematic of a multiyear plan, dubbed Sláintecare, by Ireland’s politicians and health leaders to move as much care as possible out of hospital and into the community.

Eight years after the reforms were launched, experts have said the model holds lessons for the UK government as it seeks to fix the National Health Service.

Almost 3,000 additional staff were recruited and a network of specialist hubs was established under the plan, aimed at managing patients’ conditions close to home and avoiding unnecessary hospital admissions.

Wes Streeting, UK health and social care secretary, has vowed to deliver exactly this hospital-to-home shift in England’s NHS as he attempts to reverse record-low levels of public satisfaction with the taxpayer-funded service before a general election expected in 2029.

Ireland’s performance over the past eight years demonstrates the potential prize: radically shorter waiting times for diagnosis of some conditions although patients can still face long waiting lists for hospital treatment.

But its experience also points to the hurdles that England will have to overcome if it is to embed a community-centric approach against a backdrop of faltering public finances.

The UK government’s 10-year plan has set a goal that the share of funding devoted to hospital care should fall in the coming years, allowing “proportionally greater investment in out-of-hospital care”.

A report into the NHS by Lord Ara Darzi last year found that 58 per cent of spending went on acute hospitals, based on 2021 data. Community health services made up 7 per cent of expenditure, and primary care services 18 per cent.

The Department of Health and Social Care said the report had “found that too much healthcare spending goes on hospitals, rather than care in the community, meaning that patients are not getting the early help they need”.

However, a study by the Nuffield Trust released on Tuesday shows how hard it will be for the UK government to shift the dial.

In 2017, when Sláintecare was launched, hospitals in Ireland accounted for 37 per cent of total health expenditure, according to the report. “Ambulatory healthcare providers”, such as GPs and dentists, accounted for 20 per cent.

By 2023, this distribution was still roughly the same, with 40 per cent of total healthcare funding going to hospitals and 21 per cent to ambulatory providers.

Tony Canavan, regional executive officer, West and North West for Ireland’s Health Service Executive, said it was simply “unrealistic” to believe hospital funding could be squeezed, pointing to strains on the sector which in winter could be “absolutely unbearable”.

Many staff at the front line believe investment in community services is still insufficient.

Professor Rónán Collins, national clinical lead for stroke at Ireland’s Health Service Executive, said perhaps the biggest issue was integrating patient records to allow more seamless care between hospitals and community services.

Canavan acknowledged further resources were needed but lauded “a very, very significant level of investment” in community services, “the likes of which certainly I haven’t seen in my 33 years [career] previously”.

Crucial to the successes the reforms have achieved in Ireland has been changing the way staff operate, through the introduction of new incentive structures.

GPs are paid for taking on more responsibility for chronic disease management and consultants working in community specialist teams or hubs are required to split their time between community settings and hospitals.

In contrast, while England’s 10-year plan had touched on the need for staff to work in different ways, Sarah Reed, senior fellow at the Nuffield Trust, said it still lacked clarity on “what those changes will be, and how they’ll bring staff on board”.

One other aspect of the Ireland changes is that they gained, and have sustained, backing from across the political spectrum. In contrast, England, which has had six changes of health secretary since 2020, had struggled with short-termism in its policymaking, Reed said.

Sláintecare has just two years to run on its original 10-year timetable but Canavan said it was likely to be extended for between two and four years, reflecting the interruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

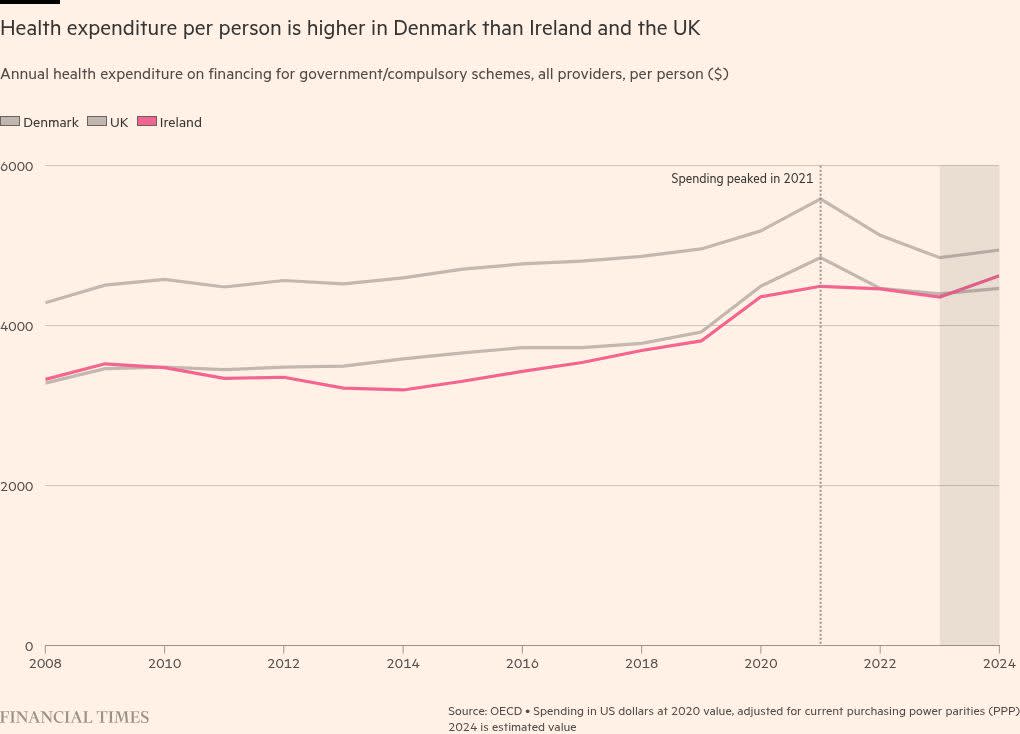

The study, which also examined Denmark, where the government has similarly embarked on a drive to move care out of hospital, notes that poor data availability in Ireland makes outcomes more difficult to track.

However, there were clear signs of “increasing volumes of activity being delivered in the community”, it said. In 2023, more than 335,000 radiology scans were carried out in community settings, an increase of more than 80,000 compared with the previous year.

Canavan acknowledges its report card so far is mixed — marred, he suggests, by a lack of clarity about how success is to be measured. But he points to radically reduced waits for some tests as just one of the boons it has delivered.

“One of our endocrinologists commented to me recently that prior to the implementation of the chronic disease management programme, the waiting list for a patient to be seen at outpatients [for possible diabetes] was over two years.” The waiting time is now up to two weeks.

Canavan added that the system had reached a stage where waiting lists were the “accepted norms”. Sláintecare, however, “has demonstrated to us that life doesn’t have to be that way”.

Data visualisation by Maya de Souza