Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ageing Japan is becoming a test bed for whether logistics companies can overcome labour shortages and maintain faster delivery times, as the bulk of the sector lags behind Amazon in embracing robots.

At its fulfilment centre in Chiba near Tokyo, where robots outnumber the 2,000 employees and storage capacity is 40 per cent higher than a regular warehouse, Amazon showcased a new paper wrapping machine that automatically adjusts to the item’s size and a dizzyingly complex sorting system that coordinates multiple items for packing into a single box or bag.

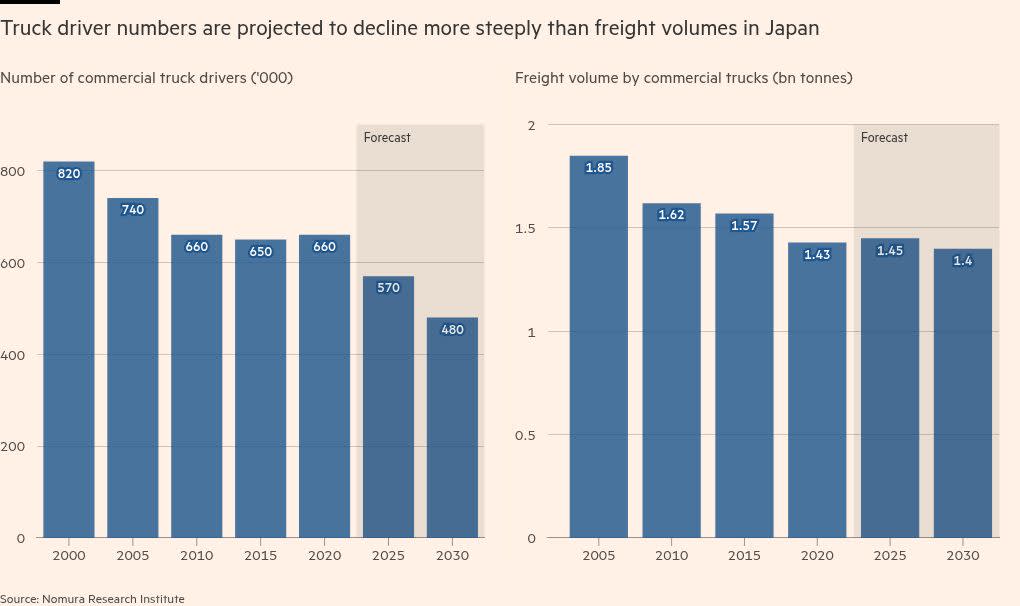

But humans take over once a package is out on the road. With almost 30 per cent of Japanese citizens over 65, the pool of truck drivers is expected to shrink by a third to 480,000 by 2030, according to Nomura Research Institute.

Amazon is going more local with automation and sees room to squeeze out efficiencies throughout the supply chain. Kohei Shimatani, vice-president of operations at Amazon Japan, said that robotics was on the verge of spreading beyond fulfilment centres to enable automated packing at smaller delivery hubs closer to customers. Automation would race ahead of Japan’s rapidly shrinking working-age population, he predicted.

“I don’t think the ageing population itself will be the showblocker” to achieving faster delivery times, such as expanding same-day delivery to more products, said Shimatani. “A lot of people are over 65 . . . but I don’t think that problem itself will be critical.”

On a global level, Amazon is introducing an artificial intelligence model called DeepFleet to control all its robots and gain a further competitive edge. The AI model has already improved the robots’ speed by 10 per cent.

However, the US company’s deeply held confidence in the power of technology to overcome labour challenges is not shared by logistics rivals in Japan that are dealing with far greater variations in customer demands and items that make standardisation and robotic handling harder.

At a warehouse in east Tokyo, Nippon Express has been testing out autonomous forklifts, automated grid-style storage and retrieval systems, robots shuffling shelves around and a high-tech mobility wheelchair for pickers.

But its executives are far from convinced that investments in automation will pay for themselves.

“If we’re just talking about simply replacing a certain workload with this technology, I don’t think we can really measure the efficacy,” said Akira Unno, an executive leading business development at Nippon Express.

“Much of this technology is in the demonstration phase. I think this is a transition period where we see whether they will undergo explosive development or whether humans are better.”

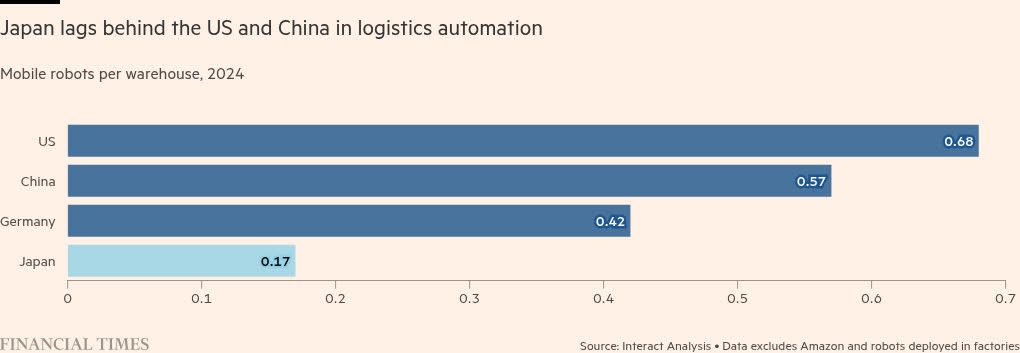

Despite the world’s fourth-largest economy being called the land of the rising robots, due to its role as the world’s biggest supplier of industrial robots, there are only 0.17 robots per non-Amazon warehouse in the country itself, versus 0.68 units in the US and 0.57 in China, according to data from Interact Analysis.

Hard-working employees, urban concentration and a slow uptake of online shopping have all contributed to Japan’s less rapid adoption of robots in logistics. The mountainous nation’s limited availability of land also means that its warehouses tend to be smaller, L-shaped, and span multiple floors, making it harder to integrate robotics systems.

“The fundamental reason for their slow rollout is the significant cost to deliver robots into existing warehouses,” said Ryoichi Kakui, chief executive at Tokyo-based e-LogiT, a logistics consultancy. “The key for third-party logistics companies to improve their efficiency is to get rid of handling exceptional items.”

Elsewhere, concerns flared up last year around what Japanese media dubbed the “2024 problem” of new legislation that restricted truck drivers’ working hours. Now, NRI’s 2030 prediction of far fewer drivers is gaining attention as Japan loses 10,000 from the industry every year.

Logistics executives fear Japan will not be able to handle any take-off in ecommerce, which is still less than 10 per cent of retail sales versus 27 per cent in the UK, for example.

SBS Holdings, one of the nation’s biggest trucking groups, is not banking on autonomous driving being the panacea in the near term. It plans to hire hundreds of foreigners in the coming years to work as truck drivers.

For Nippon Express and its peers, the calculus for introducing robots is evolving beyond a simple comparison of cost savings to one of whether Japan can keep delivering.

“We can see that there definitely will not be enough human resources and we see no response to the [low] birth rate. There’s only 1mn people who are 18 years old — there used to be 2mn,” said Unno.

“The discussion quickly turns to: ‘How many years will it take to recoup the investment?’ — and that’s understandable. But that’s not the only point . . . there’s also the fundamental question of whether we can even maintain the supply chain.”