Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Four months ago Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa said the IMF was “stupid” when it lowered growth forecasts for Indonesia as clouds gathered over south-east Asia’s largest economy.

At the time Purbaya was a relatively unknown finance sector official. But he now has the chance to put his challenge to economic orthodoxy to the test, after being appointed finance minister in one of President Prabowo Subianto’s biggest gambles of his first year in office.

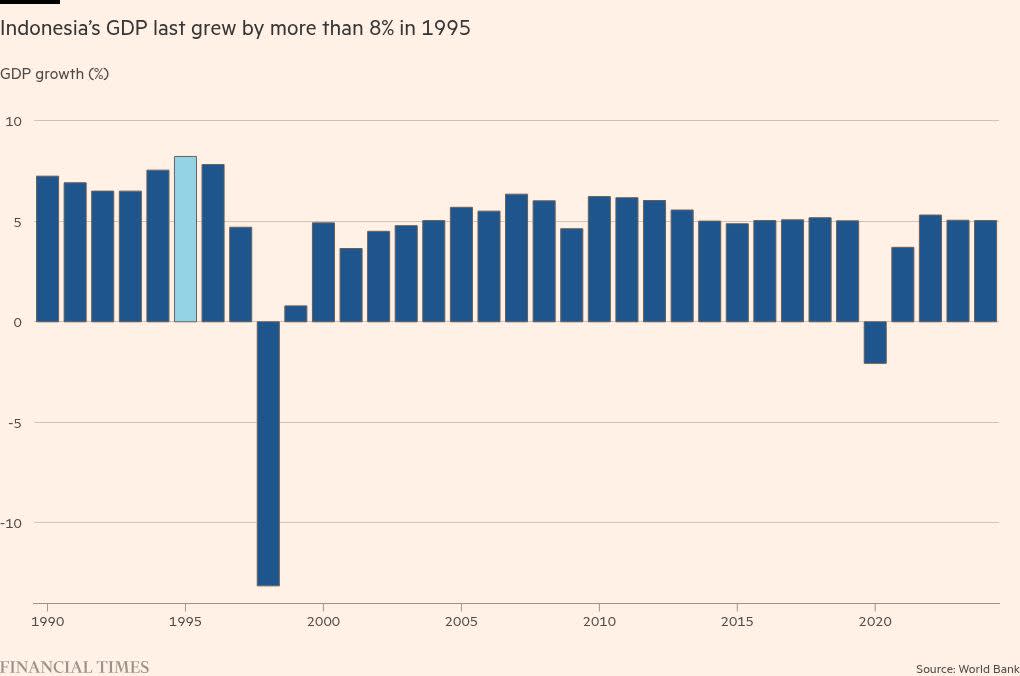

The president abruptly removed Sri Mulyani Indrawati, renowned for her insistence on fiscal prudence, after a wave of violent protests in which 10 people died. In Purbaya, Prabowo has turned to a pro-growth champion to support his ambition of 8 per cent annual economic growth — a rate the country last achieved in the 1990s.

“We can build the foundation to faster growth relatively easily,” Purbaya said on Thursday, in his first comments since taking office. “As long as we can manage domestic demand with the right fiscal and domestic policies, we can grow relatively well.”

Yet the change of minister has also unnerved investors and economists, who worry that Indonesia could exceed a self-imposed deficit limit of 3 per cent — an anchor for attracting foreign investors — and cause market turmoil.

Many do not believe Purbaya’s job will be easy. Indonesia, the world’s largest nickel producer, has drawn foreign investment over the past decade and its vast mineral resources have made it integral to green tech and electric vehicle supply chains. But it is now saddled with a sharp slowdown in consumption, lower purchasing power and a weak jobs market.

Economists have warned that the current growth rate of 5 per cent would be impossible to maintain in the near term and questioned whether Purbaya could secure faster growth without widening the fiscal deficit. In April, the IMF lowered the 2025 growth forecast to 4.7 per cent from 5.1 per cent.

“When the rubber hits the road we need to see . . . do we stay with [fiscal] orthodoxy, or do we get a bit more caution thrown into the wind and a wider deficit going forward, with the goal of trying to hit their GDP growth targets,” said Mark Ledger-Evans, emerging market fixed income portfolio manager at Ninety One.

Sri Mulyani, finance minister under three presidents, saw fiscal discipline as critical to attracting foreign funds and winning investment-grade credit ratings after the Asian financial crisis.

But Purbaya has blamed past fiscal and monetary “mistakes” for the recent spate of protests and said next year’s fiscal deficit targets could be revised as he looks to amend Sri Mulyani’s 2026 budget.

Purbaya has admitted colleagues have described him as having a “cowboy style”. Still, he has vowed to maintain the legally mandated fiscal deficit cap of 3 per cent, despite Prabowo’s previous calls to remove the ceiling.

Prabowo won last year’s election in a landslide on the back of populist pledges, the biggest of which is providing free meals for school children at an expected cost of $28bn a year. He is also planning free health checks and the construction of 3mn homes for lower-income groups.

However, many have questioned whether these programmes are the best use of state funds at a time when Indonesia’s economy is struggling. Purbaya’s appointment caused market jitters, with the rupiah sliding more than 1 per cent.

Teuku Riefky of the University of Indonesia’s Institute for Economic and Social Research said Purbaya’s support for populist programmes would “limit our fiscal space”, as the government had failed to boost revenue adequately.

“The MoF . . . is now under increasing pressure from the push for populist programmes that the new minister seems set to continue,” he said.

Purbaya emerged as Prabowo’s choice in recent months thanks to his enthusiasm for the president’s growth targets, according to three people familiar with the matter.

In a July presentation to Prabawo and his inner circle seen by the Financial Times, Purbaya advised that “to accelerate economic growth sustainably, the fiscal and monetary growth engines need to be stimulated and synchronised”.

In comments to parliament this week he said severe austerity measures this year — including cuts to travel and allocations for infrastructure and education — needed to be reviewed.

On the monetary front, Purbaya’s presentation said not enough had been done to defend the rupiah. A weaker rupiah makes imports of raw materials more expensive, affects business profitability and increases local prices. Indonesia’s central bank has consistently supported the currency this year as it slid because of concerns over Prabowo’s spending plans.

Purbaya also proposed moving towards private-sector driven growth, away from state-driven largesse, arguing that it would lessen the fiscal burden.

In his first week as finance minister, he said the government would transfer $12bn of its cash reserves to the banking sector, to boost liquidity and stimulate growth.

However, some economists said that weak demand was the issue, not the lack of liquidity.

“Liquidity markers are already in ample territory, suggesting that any positive impulse to credit activity will also need an improvement in demand from households and corporates,” said DBS senior economist Radhika Rao.

As Purbaya moves to reset economic policy, investors will closely watch for signs that Indonesia might loosen fiscal discipline — which will be critical for bond and equity investors, Ledger-Evans said. “If we lose that anchor, then it starts to become a less compelling market to invest in.”