As Papua New Guinea prepares to mark 50 years as an independent nation next month, the country will sign a defence treaty with Australia, binding it closer again to its former colonial overseer.

The treaty will allow Papua New Guinea nationals to gain Australian citizenship by serving in its defence forces, deepen defence cooperation, and give both countries’ militaries greater access to each other’s bases.

“Our security and prosperity is entwined with their security and prosperity: this defence treaty will take that to an even higher level,” Australia’s minister for defence industry and the Pacific, Pat Conroy, said this week.

His PNG counterpart, Billy Joseph, described the treaty as an agreement that “sends a message: with all these competing interests in the region, PNG stands with Australia”.

There is a bigger contest in play. Papua New Guinea sits at the centre of broad geopolitical battle that stretches right across the Pacific: a contest between the world’s great powers for influence, for access, and for loyalty. For PNG that contest presents a delicate balancing act, but also opportunity.

PNG’s defence treaty with Australia will be signed on 15 September, one day before the country celebrates its 50th anniversary of independence from Australia.

But this day could have looked very different.

Port Moresby sources say PNG was close to signing a policing and security deal with China last year, before Australia stepped in with an offer to fund a PNG team in Australia’s national rugby league competition.

“If it had been a footy match, it was pretty much close to full-time and coming down to the wire,” a source, familiar with the diplomatic situation in the Pacific told the Guardian.

The contest between China and Australia for influence in the region is a “diplomatic knife fight … a daily battle and permanent,” the source said.

Rugby league is PNG’s national sport – a countrywide obsession – and the chance to play in Australia’s premier competition was too great a lure to resist, even coming, as it did, with the caveat that PNG could not sign a security or military agreement with China.

Australia will spend $600m over a decade supporting the new Port Moresby team, but the funding is contingent upon PNG not entering a security agreement with any country outside the so-called ‘Pacific family’, a term widely used to specifically exclude China.

If Canberra pulls its funding, the NRL is obliged to drop the PNG team.

The Guardian understands there were serious concerns about China gaining a security foothold in PNG, which would have repercussions for Australia and its allies.

At a speech in Brisbane this week, Conroy said “we’re in a permanent state of contest for influence in the region, and we’re committed, we’re fighting every day to be the partner of choice for the Pacific.”

Conroy cited the rugby league deal as one only Australia could make with PNG.

“We are using rugby league as a tool of soft power diplomacy to bring our two countries closer together.”

A balancing act

China is omnipresent across PNG: PNG was the first Pacific country to sign on to Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative, and China has funded stadiums and highways, convention centres and universities, in the capital and elsewhere. Beijing has also provided concessional loans to build critical infrastructure, like the national power grid, submarine cable networks, and telecommunications bases.

More broadly across the Pacific, China’s presence is similarly conspicuous – a presidential palace built in Port Vila, a brand new sports stadium in Honiara, two aircraft carriers operating in the Pacific for the first time – contrasted against a sense that the US’s historical presence as a Pacific power is no longer backed up on the ground.

In recent years, Washington has sought to rebuild influence across the Pacific, establishing or re-opening embassies in Fiji, Tonga, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu.

In PNG, the half-billion dollar Lombrum naval base upgrade on Manus Island – to which both the US and Australia contributed – will give both navies access to the base and shore up “a gateway to the Western Pacific… a really strategically significant place” in the words of Australian defence minister Richard Marles.

PNG’s defence minister , Billy Joseph, was unambiguous when visiting Canberra in June: “when it comes to security, we choose our traditional partners, which is Australia [and the] US.”

While PNG is drawing closer to the US and Australia on matters of security, Moresby’s diplomacy is a balancing act: it does not want to shut the door to Chinese investment in the country, particularly around infrastructure and critical development projects.

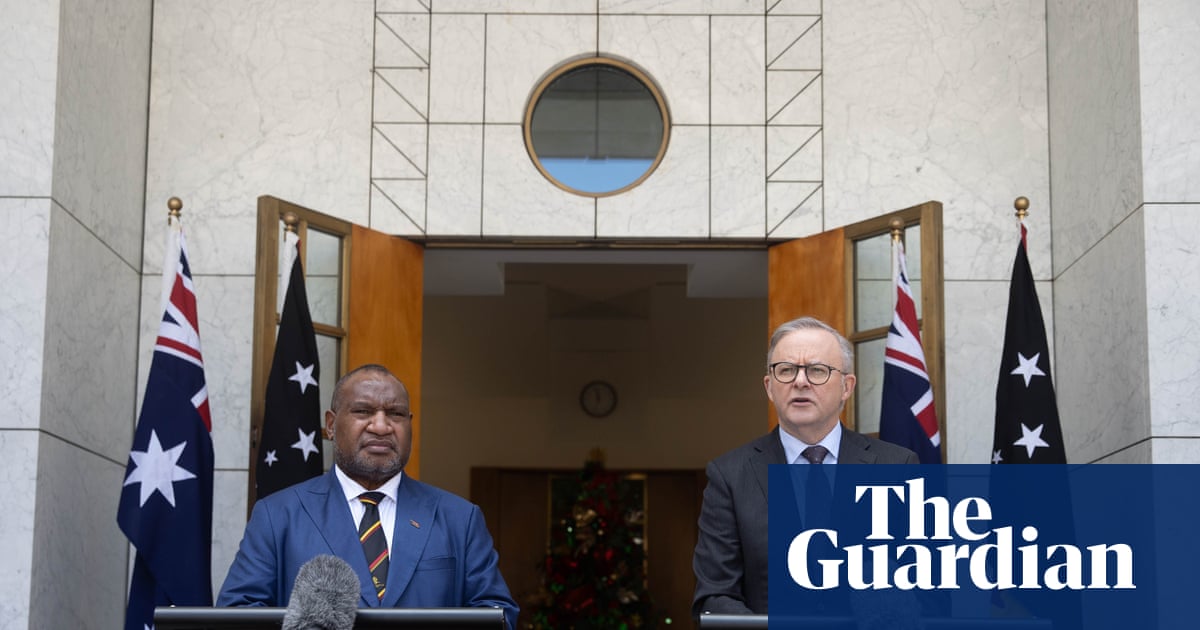

James Marape, PNG prime minister through six tumultuous years, is fond of Papua New Guinea’s longstanding foreign policy aphorism: “friends to all, enemies to none”. But Marape is a canny politician too. In the great power contest lies opportunity.

The prime minister has been adroit in using the flood of foreign interest in PNG to leverage investment into his country, both for the benefit of the its people, and to quieten domestic political criticism and stabilise his own leadership. There is much that needs shoring up: endemic corruption; adaptation to climate change; fragile health and education systems – that all stifle economic development and contribute to instability.

Marape has said his country will seek security from PNG’s traditional partners – in particular Australia and the US – but says his country, desperate for development, cannot ignore China’s trade and development overtures.

“We will not compromise our relations with China just as much as we will not compromise our relations with the USA,” he told a university audience in Canberra last year. “We also believe that someone else’s enemy is not my enemy. We maintain good relations with all nations.”

Patrick Kaiku, teaching fellow in the political science department at the University of Papua New Guinea, tells the Guardian that while foreign policy great power rivalry is a priority, for Port Moresby’s political elite, ministers and business leaders, it “does not pre-occupy the daily conversations of most Papua New Guineans”.

“Our political leaders and those who conduct our diplomacy do not connect with the aspirations of people [in PNG] in general.”

On the streets of Port Moresby, or in the communities of the Highlands, the idea of PNG as a prize to be won in some zero-sum geo-political contest is of little interest. It is the more fundamental concerns – security at home, healthcare and education- that dominate daily lives.

Kaiku argues PNG should do more to recognise its own influence.

“If we’re trying to talk back, when we’re trying to communicate with these great powers, we need to talk about what matters to us: and it’s mostly non-traditional security issues like climate change and food security, or our population and unemployment.”

Kaiku sees Marape as adept at winning from foreign powers something to help not only his people, but his own political fortunes. This is how Papua New Guinea’s diplomacy is best understood, Kaiku says.

“It is not done on a coherent set of foreign policy agendas, but our political leaders are just capitalising on this great power rivalry, to enrich their own political base and support, but also to fulfil domestic constituency demands.”

However, Kaiku argues, as the US-China contest in the Pacific grows ever more acute, the ideal of “friends to all, enemies to none” will become harder to maintain. The balancing act becomes more delicate, and superpowers will increasingly insist countries like PNG declare a side.

“It’s a rhetoric. It’s very idealistic. But in the real world of realpolitik, it may not work. If you’re dealing with Trump, or we’re dealing with some of these world leaders, you may need to take sides.”

with Andrew Messenger