Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

The writer is a former policy adviser at the Indian Ministry of External Affairs

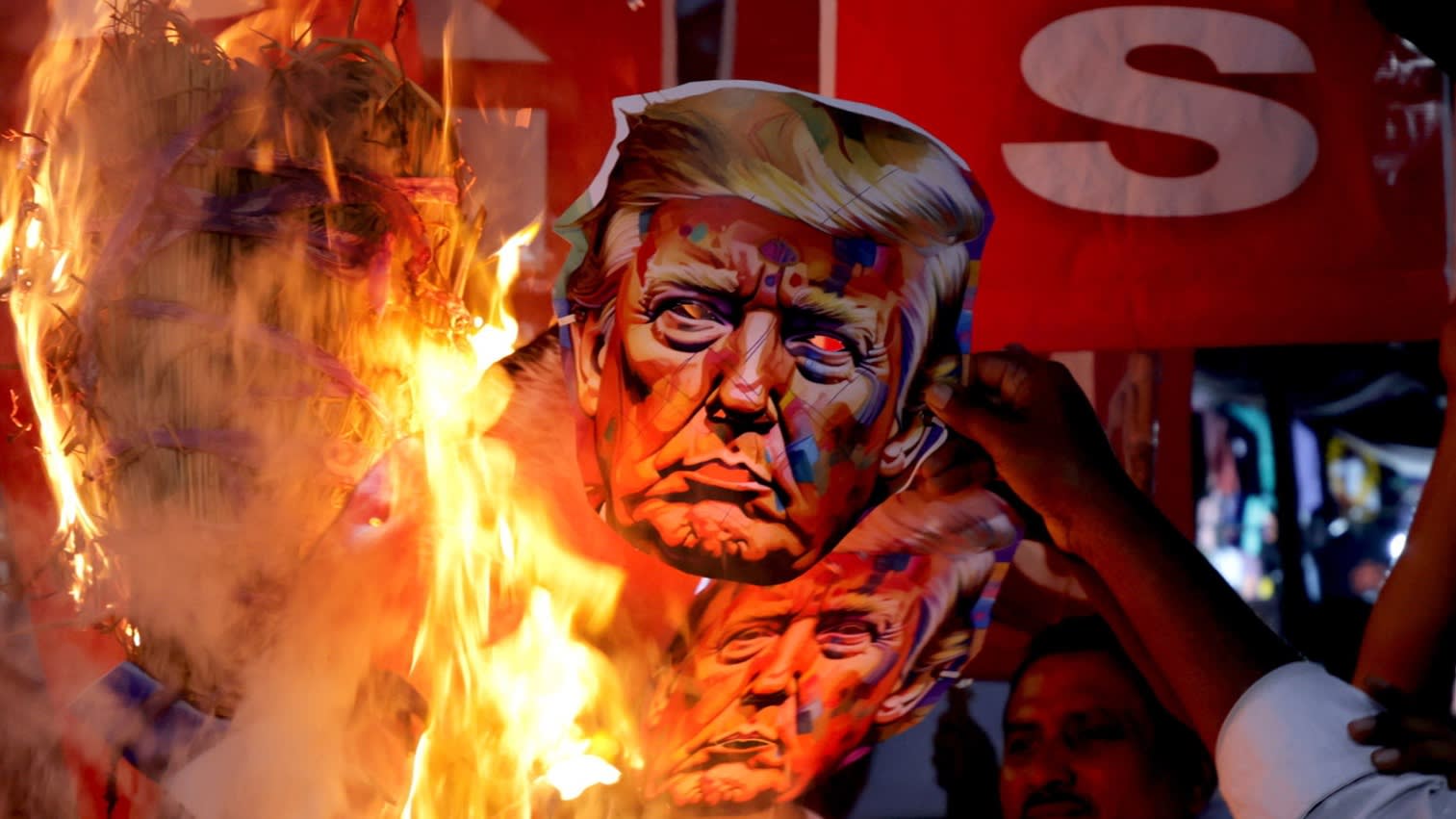

After a quarter-century of warming ties accompanied by assiduous, bipartisan nurturing by governments in both countries, relations between India and the US have hit a diplomatic air pocket. India’s oil purchases from Russia are at the heart of the turbulence. The administration of Donald Trump has claimed these purchases are funding Vladimir Putin’s war machine. Consider the facts.

India was a marginal buyer of Russian oil until the Ukraine war upended energy markets. At that stage, it was out-priced by Europe in its traditional Gulf sources. Like other energy-importing countries, it found oil and gas spot markets and contracts skewed by the entry of high-income European nations as buyers. India therefore had little choice but to turn to the only large available option: Russia.

India was even encouraged in this endeavour by the previous US administration, whose officials publicly stated that this step contributed to global energy market stability and kept prices manageable. The Trump administration seemed to be going along with this approach, until one day, without warning, it changed its mind. Interestingly, President Putin, in his remarks in Alaska, said US-Russia trade increased by 20 per cent after President Trump came to office.

India is not the only nation trading with Russia, not even in the narrow energy sector. China is the biggest importer of its crude oil and coal. The EU is the largest customer of Russian LNG and pipeline gas. The EU’s LNG imports from Russia have risen in the past year, reaching record levels. Turkey receives crude oil, oil products and pipeline gas. Surely these countries don’t get energy supplies for free from the Russians?

Are America’s hands clean? Despite the Ukraine war, the US continues to import fertilisers from Russia for its farmers, as well as from Belarus. It buys Russian uranium and plutonium for its nuclear industry. Its electronic and automobile industries source palladium from Russia. All these are justified as economic imperatives. Other nations may feel similarly compelled.

The energy trade is not Moscow’s only economic instrument. Russia obviously benefits from what it imports from the rest of the world. India’s own exports to Russia are minimal, less than £5bn annually. Other close allies of America, however, have a much more robust trade account. Yet that does not seem to matter to hypocritical critics. Compare India’s numbers to the EU’s exports of £34bn to Russia, Turkey’s contribution of $9bn, and China’s mammoth £115bn.

Admittedly, the EU figure has fallen significantly since 2021. Even so, this decline is not as straightforward as it appears. As a Brookings Institution publication pointed out in September 2024, EU exports — particularly from Germany and Italy — to central Asia and the Caucasus have risen sharply since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. “This export boom,” the report said, “is so large that it cannot conceivably be targeting domestic demand in these countries.” It suggested instead “transshipment of goods . . . [that] may be disproportionately important for Russia”.

American officials have also argued that India uses US trade dollars, ostensibly derived from its surplus, to buy Russian oil. As anyone with common sense would recognise, a trade surplus with the US has no linkage with buying energy elsewhere. Indeed, that logic if anything would be even stronger in the case of the EU and China. They run much larger surpluses with the US and record much bigger trade with Russia.

Frankly, India is being picked on because its trade negotiations with the Trump administration have still not concluded. It is resisting unreasonable demands and unfair expectations. The selective targeting for condemnation of India’s oil purchases from Russia will be interpreted as exerting pressure on New Delhi’s trade negotiators. The agenda is selfishly American, however sanctimonious the logic that cloaks it.

The upshot is both disappointing and unsustainable. It places at risk decades of mutual political trust. This week a White House spokesperson referred loosely to “sanctions on India”. Treasury secretary Scott Bessent and White House counsellor Peter Navarro have both made critical — and to Indian minds, again hypocritical — comments. Repercussions could be far-reaching.

Strategic partnerships cannot be built on spurious arguments, unjustified trade demands and unilateral expectations of exclusivity. They need mutual respect and a recognition that relationships are not a one-way street.