Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The geography and character of modern nation states often seem inevitable, even immutable, to those who live in them, particularly to the vehement nationalists now on the rise around the world.

Sam Dalrymple’s Shattered Lands, which examines with pace and verve the break-up of the vast domains of British India in the 20th century, reminds us that very little about the shape of today’s nations was predictable ahead of their creation and that nothing was inevitable.

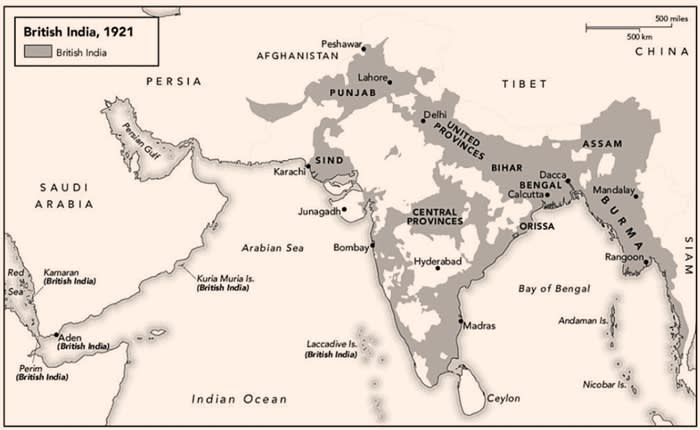

Famines, wars, religious uprisings, charismatic leaders, assassinations, improbable political alliances and chance events have always bent the course of history in unexpected directions, sometimes only weeks or days before the creation of a new country. The area of British imperial control — the “Raj” — extended from the Arab sheikhdoms of the Gulf across the Indian subcontinent to Burma (now Myanmar) in the east. Before 1928, a quarter of the world’s population lived in this vast British-Indian territory.

“And then, in the space of just fifty years, the Indian Empire shattered,” writes Dalrymple, with the five partitions of the title carving out a dozen new nations, triggering huge migrations of people and civil conflict, and leaving “a legacy of war, exile and division” that persists to this day.

As the historian Patrick French is quoted as saying, few moments in modern history “have had a more lasting impact on so many people” or were so ill-planned. “Many of the key events of the 1940s were the result of chance, or even of error, and some of the most important decisions of the period were made on an almost random basis.”

Pakistan, the “Land of the Pure”, far from being inevitable, was only coined as a word in 1933 by a Cambridge student called Rahmat Ali Choudhary (P for Punjab, A for Afghania, K for Kashmir, S for Sindh and TAN for Baluchistan). Even the country’s founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah initially dismissed the idea as “some sort of Walt Disney dreamland, if not a [HG] Wellsian nightmare” and only belatedly pushed for a separate homeland for Muslims.

Nationalist movements, helped by the hasty departure of a weakened Britain from its colonies after the second world war, did succeed in creating India, Pakistan, Burma and eventually Bangladesh, but neither the borders nor the populations within them were foregone conclusions.

Nepal and Bhutan also emerged as independent kingdoms, but few of the 565 Indian princely states that fell outside the direct control of the Raj survived, not even the powerful state of Hyderabad, once a cultural beacon of the Islamic world, whose Nizam was considered to be the world’s richest man. Nor did the Naga, the Mizo, the Pashtuns, the Baluchs or the Sikhs achieve the independence that some of them craved.

Of the five partitions described by Dalrymple (son of historian William Dalrymple), the best known is the “Great Partition” of India and Pakistan in 1947, which was eventually followed in 1971 by the creation of Bangladesh out of East Pakistan. Much has been already written about those two cataclysmic south Asian events, and one of the merits of Shattered Lands is its analysis of the other three: the largely forgotten removal of Burma from British India after 1937; the partition (though it was more like an absorption by India and Pakistan) of the princely states; and above all the separation from India of the Arabian peninsula, starting with Aden and ending with the transfer of the Gulf states from the Indian Political Service to British control before their oil wealth was fully apparent.

“Without this minor administrative transfer, it is likely that the states of the Persian Gulf Residency would have become part of either India or Pakistan after independence, as happened to every other princely state in the subcontinent,” Dalrymple writes. “In hindsight the negotiations read like India’s greatest lost opportunity, willingly giving up the combined oil wealth of Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and the UAE.”

Dalrymple’s history of British India’s demise ends with a description of a virtual reality project he helped launch to allow a few of partition’s victims to revisit their ancestral homes in Pakistan and India, and an impassioned warning about the dangers of nationalist mythmaking and “historical amnesia” in Asia, the Gulf and Britain itself.

“The last decade has witnessed the decline of globalisation, the strengthening of borders and the resurgence of nationalism across the world,” he writes. “India’s partitions are a dire warning for what such a future might hold.”

Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia by Sam Dalrymple William Collins £25, 528 pages

Victor Mallet is author of ‘River of Life, River of Death: the Ganges and India’s Future’

Summer Books 2025

The best titles of the year so far. From politics, economics and history to art, food and, of course, fiction — FT writers choose their favourite reads of the year so far

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X