On a blistering summer evening in Nagpur, a city in Central India, a sea of almost a thousand men clad in brown trousers, crisp white shirts and black caps stood stiffly, as a saffron-coloured flag quivered up a mast.

A whistle shrieked and the graduating karyakartas, or “workers” — most of them moustachioed, some of them wiry, others with bulging bellies over their belt buckles — held their right arms and open palms stiff across their chests in salute, followed by a quick head bow. To the background of beating drums, they chanted in Hindi: “The collective consciousness of the people is awakening; change is surely coming.” At their sides they carried lathis, sturdy bamboo sticks.

The graduation ceremony marked the end of a month-long training programme, designed to be character-building, “man-making” and to mould the men into a brotherhood of Hindu nationalists, part of a long campaign waged by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, or National Volunteers’ Organisation, which marks its centenary in September. This all-male group has become arguably the largest far-right movement in the world, with, it is claimed, some six million members. Crucially, it forms the heart, soul and muscle of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata party, which is steeped in RSS ideology and has been accused of turning India into a Hindu nation at the expense of its Muslim minority.

That ideology imagines India to be a Hindu state. It is deeply suspicious of, and often hostile to, the country’s minority faiths. “From its inception, the goal before the Sangh was to attain the pinnacle of glory of the Hindu Rashtra [nation] . . . through organising the entire society,” reads the RSS mission statement. The 21st century will be “dominated by Hindutva” or “Hindu-ness”.

Mohan Bhagwat, the RSS chief, or sarsanghachalak, gave the graduation speech. “Our society needs to be vigilant and united,” he said. “While we celebrate our diversity, I will speak my language with pride, and my faith is dear to me. These are my unique identities — and I want to protect them.”

Bhagwat is not alone in harbouring such feelings in India today. The perceived threats to Hindu identity he alluded to included those posed by neighbouring Pakistan to the west and by Bangladesh to the east as well as from an enemy within — India’s religious minorities. Modi has expressed similar fears. The prime minister has been a member of the Sangh since his youth, and went through the same set of rites as these men. He was a pracharak, or full-time RSS worker, until he entered politics in the 1980s.

Backed by the Sangh’s extensive and powerful network, Modi rose to become India’s most powerful and consequential leader since the independence hero Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister. Nehru, a secular social democrat, stood in opposition to the Sangh, comparing the organisation to Germany’s Nazi party. But the days when it could be seen as a fringe group are in the past, and in 2025 the RSS will be able to celebrate its centennial underpinned by the BJP’s longest period in power, under the leadership of a leader who is reshaping the country according to its ideals.

In Nagpur, the new graduates buzzed with enthusiasm about the anniversary. Suraj Jangid said he had been part of the RSS since he was nine. “This is a proud moment for me because the RSS was formed in 1925 and I’m graduating in its 100th year,” said the 31-year-old entrepreneur from Rajasthan. After completing the demanding 25-day boot camp, Jangid is now part of the RSS’s highly trained cadre of volunteers, the karyakartas. His journey began as a boy when he stumbled upon a local branch of the organisation while playing in a park. Some two decades later he is convinced that the RSS is unstoppable. “The future of Bharat is ours,” he said, using the Sanskrit term for India, before being whisked away by an RSS orderly.

Over the past century, much of the Sangh’s daily work has been pragmatic. Through what it calls its Sangh Parivar (family organisation), it carries out social work across the country through some three dozen sister organisations — the student wing alone has more than 5.5 million members. At the core of the RSS itself are the shakhas, or 83,000 local branches, a network it describes as “a laboratory where we are engaged in building up national and social character”.

The volunteers carry out more than 122,000 service projects all over the country. Following June’s fatal air crash in the north-western city of Ahmedabad, in which all but one of the 242 people on board, as well as 19 on the ground, died, uniformed RSS members were seen manning the mortuary at the hospital. “The Sangh’s work has been increasing, despite all the indifference, ridicule, opposition and resistance from its critics,” wrote Manmohan Vaidya, an RSS joint general secretary.

The criticism he referred to includes accusations of bigotry and animosity towards India’s Muslim community. RSS leaders say members are free to practise any religion, as long as the worship is done within the framework of cultural Hinduism and with respect for India’s traditions. “Though it talks about Hindu religion, it is not a religious organisation. The RSS was created for nation-building,” said Sunil Ambekar, the organisation’s chief spokesperson. “The purpose is to be proud of your ancestors, of your dharma, which does not mean religion but duties, ideas and values,” he added. “It’s an emotional bonding and cultural continuity.”

To its volunteers, or swayamsevaks, the RSS offers the inclusion and support of a tightly knit community. Workers “are taught to think of themselves as a family — a brotherhood — with a mission to transform Hindu society”, wrote Walter Andersen and Shridhar Damle in The Brotherhood in Saffron, a book about the organisation. “The message of the daily meetings is a restoration of a sense of community among Hindus”, especially those feeling “rootless”. To “build fortitude” of mind and spirit, volunteers wear uniforms, including pleated shorts; play games, such as kabaddi, an Indian blend of wrestling and tag; duel with their lathis; sing nationalist songs; and learn Hindu-centric philosophy and history.

“As long as I remember, I’ve been in my RSS uniform. I have no other memory of childhood,” said Ratan Sharda, who has written several books about the Sangh. “At a young age, you don’t think of leaders. You enjoy the games, songs. You listen to the teachers.” Sharda joined at the suggestion of his uncle, who, in 1947, was a founding member of the Kenya unit of the RSS’s foreign branch, the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh, which is now present in about 35 countries.

To its critics, however, all that is only the tip of the iceberg. “They want to change society,” said Christophe Jaffrelot, a south Asia expert and professor at Sciences Po and King’s College London. “They want to change the mindset of the people . . . And this is a long-term agenda. The whole family is a huge network, infiltrating all kinds of milieu, including the judiciary, including the army, including the business community. They are everywhere, all trained in the same way, under the same ideology. We have to look at the whole to see the real impact.”

The writer Devanura Mahadeva was briefly part of the Sangh during his high school years in Karnataka and later became disenchanted. In his critique RSS: The Long and Short of It, he writes that “history is whatever they believe . . . for the RSS, their beliefs are the truth. Their beliefs must shape the present.”

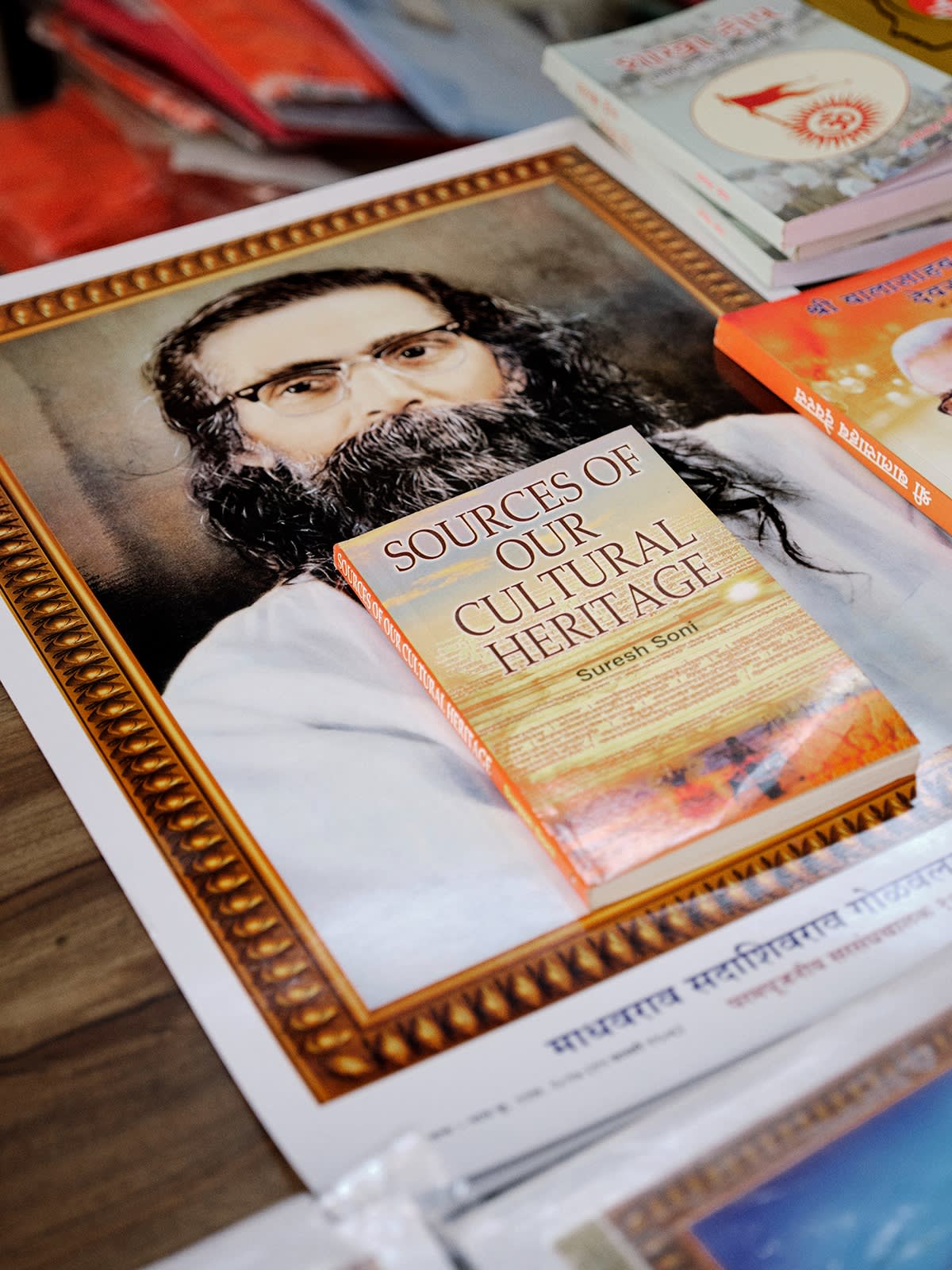

Only two portraits were on display at the graduation ceremony in Nagpur. One of Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, the physician who founded the RSS in 1925 and remained its chief until 1940, and another of Madhavrao Sadashivrao Golwalkar, the self-styled guru who headed it for the critical period from 1940 to 1973. Those years saw the trauma of India’s Partition and the creation of Pakistan and later Bangladesh, the assassination of independence leader Mohandas Gandhi by a former RSS member and successive backlashes against the organisation.

The major difference was that the RSS was rooted in the ideology of Hindu supremacy, specifically ideas about territorial nationalism. In his 1923 work, Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?, the politician, activist and writer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar sought to separate India’s religions. Savarkar included Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs among those religions that had originated in India, but he was sceptical of whether incomers like Muslims and Christians could ever be loyal to a Hindu state.

A 1933 government intelligence report shows that during a speech in Nagpur, Hedgewar “claimed that Hindustan was for the Hindus, that Hindus would dominate the future government of India, and it was for them to say what political rights and privileges were to be conceded to non-Hindu elements”. The report concluded: “It is perhaps no exaggeration to assert that the ‘Sangh’ hopes to be in future India what the ‘Fascisti’ are to Italy and the ‘Nazis’ to Germany.”

Building on those ideas came the Sangh’s second and, arguably, most consequential leader, Madhavrao Golwalkar. It was “Golwalkar’s political clarity, which now became central to the ideological training of the RSS men, that brought to the militia a sense of confidence it had never experienced before”, said Dhirendra K Jha, author of Golwalkar, a biography of the leader.

For Golwalkar, successive Muslim dynasties, which had ruled over much of India for centuries, were despoilers. “Ever since that evil day, when Moslems first landed in Hindustan, right up to the present moment, the Hindu Nation has been gallantly fighting to shake off the despoilers,” he wrote in his 1939 book, We or Our Nationhood Defined.

Jha argues that Golwalkar considered the Nazi treatment of Jews up to 1939 to be a blueprint for dealing with Indian minorities, particularly Muslims. “To keep the purity of the race and its culture, Germany shocked the world by purging the country of the Semitic races — the Jews,” Golwalkar wrote. “Race pride at its highest has been manifested here. Germany has also shown how well nigh impossible it is for races and cultures, having differences going to the root, to be assimilated into one united whole, a good lesson for us in

Hindustan to learn and profit by.”

Today, the Sangh claims that We or Our Nationhood Defined “is neither a part of the official literature of the RSS nor [does] it reflect the view of RSS about minorities”, and that it was written before Golwalkar took the reins of the organisation. Decades later, Golwalkar himself said, “I do not distinguish between Hindus and Muslims.”

After Partition in 1947, the mistrust of outsiders grew. Two regions with non-Hindu majorities, Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir, saw violent insurgencies. These, and a war with China, put the RSS on a more determined standing at a time when Nehru was steering India towards a secular democracy. Many Hindus felt Nehru’s party was too welcoming of Muslims.

For Nehru, a Cambridge-educated Fabian socialist, the philosophy of Hindutva was anathema to the notion of a modern, independent India. In a speech in 1947 to pay homage to Gandhi on his birthday, Nehru said he strongly opposed the demand for making India a Hindu state calling it “not only stupid and medieval but also fascist in nature. Those who put forth such ideas will meet the same fate as Hitler and Mussolini.” Months later, Gandhi was killed by a radical Hindu nationalist, Nathuram Godse, who had once been a member of the RSS, sparking national outrage.

The RSS attempted to distance itself from Godse, and Golwalkar issued a statement condemning the “exceptional brutality” of Gandhi’s murder. Still, the Sangh was officially banned and Golwalkar imprisoned for six months. Later, at the peak of the cold war in 1963, when Golwalkar was trying to position the RSS as a bulwark against communism, Nehru made it clear to a group of young diplomats that “the danger to India, mark you, is not communism. It is Hindu rightwing communalism.”

The RSS was banned again from 1975-77 when emergency powers were applied across India by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who curtailed civil liberties, suspended rights and jailed rivals. Such pressure prompted the organisation to seek a political vehicle to strengthen its position. The Bharatiya Jana Sangh, founded in 1951, was merged into a shortlived governing coalition from 1977-79, before giving way in the 1980s to the BJP, which rules India today.

Though the RSS’s current leader Mohan Bhagwat has a state-provided security detail on par with top government ministers, and RSS affiliates operate in areas directly impacting public policy, members of the Sangh’s upper echelons insist they are not a political organisation.

Over the years, that case has become harder to make. In 2002, when Narendra Modi was the BJP’s chief minister of the state of Gujarat, a series of deadly anti-Muslim riots brought renewed attention to the RSS. Modi’s state government was accused of complicity in the violence. In 2012, an investigation by the Supreme Court of India cleared him of the allegations. In the aftermath of a 2009 BJP electoral defeat, the RSS threw its weight behind his candidacy for prime minister in the 2014 parliamentary elections.

Modi was a forceful and decisive leader with Hindutva credentials that might glue together a fractious BJP. Tens of thousands of RSS volunteers were involved in distributing his campaign material and helping to organise party meetings. “Never before had the RSS membership worked so hard — and so enthusiastically — on behalf of its political affiliate,” Andersen and Damle wrote in their latest book about the rise of the organisation. It worked. Modi was victorious. “What has happened in India in the last 11 years is that wherever the RSS goes, the state goes. Modi has turned the RSS into a huge non-state player,” said Golwalkar’s biographer Jha.

In his office in Delhi, Prafulla Ketkar, the editor of the RSS weekly mouthpiece, Organiser, saw it more as an “organic relationship” where “the RSS is ideologically the inspiration, but structurally and functionally the BJP is autonomous”. To others, that line can seem faint. “Golwalkar did not want RSS people to become politicians because they would become dirty, forget the rules, the values,” Jaffrelot said. “But they are political in many ways, including the vision of the nation. They want minorities to become second-class citizens. If this is not politics, what is politics?”

Some RSS leaders are uncomfortable about the cult of personality around Modi — who claimed last year that he believed he was not born biologically but had instead been sent by God. It goes against their philosophy that loyalty lies with the Sangh and not with a single man. For Jaffrelot, this “is a real strength that led them to survive for 100 years, compared to fascist parties, which had a tough time after their leaders disappeared”.

“No other far-right movement has been expanding for 100 years,” Jaffrelot added. “It is unique. And it is because of this absolute loyalty to the organisation.”

Despite that, said Jaffrelot, it is hard to see how the RSS could ever turn its back on Modi. He “cannot be more faithful to their ideology and has given them everything they ever wanted”. That includes appointing several of its members to cabinet positions; doubling down on policing the slaughtering of cows, which are sacred for Hindus; revoking the semi-autonomy of India’s only Muslim-majority region; building a temple at the site believed by Hindus to be the birthplace of the Hindu deity Rama, on ground where a violent mob had razed a 16th-century mosque in the 1990s; and even replacing the name India with the Sanskrit-origin version, “Bharat”, when New Delhi hosted the G20 summit in 2023. “There are so many policy changes which have happened according to the vision of RSS, so we appreciate it,” said a senior RSS official in Nagpur.

The proportion of Muslim lawmakers in parliament has shrunk under Modi, and in April it passed a controversial bill that would put properties given as endowments by Muslims for religious or charitable use under government control. Meanwhile, the BJP has pushed to tighten laws on religious conversions. RSS members accuse Muslim men of carrying out “Love Jihad” by courting Hindu women in order to convert them, in a country where Hindus continue to make up about 80 per cent, and Muslims 14 per cent, of the total population of 1.46 billion people.

If Modi enjoys widespread approval in the Sangh, it is because his actions and policies align with the historical goal set out by Hedgewar and Golwalkar — to make India a Hindu-first nation — never mind whether that is achievable. Jaffrelot thinks it is not: “They live in a fantasy dream about an ideal world that will never come. It’s an endless quest that can never be achieved. You will never be sufficiently Hindu. You will never be sufficiently strong.”

Bhagwat, the current RSS chief, disagrees. Before the graduation ceremony, dressed in a pressed white kurta and sporting an orange bindi on his forehead, he quipped as he exited the headquarters that the RSS’s “future looks good — strong”. He told the Organiser in May that it will take just another quarter of a century “to unite the entire Hindu society, and take Bharat to the pinnacle of glory — and eventually, to extend this transformation to the whole world”.

The goal of a Hindu nation has not yet been fulfilled, but for the Sangh to survive another 100 years, the marching karyakartas of Nagpur must believe it will be, one day soon. “May the glory of Mother India resound on the global stage, and may there be a definite transformation,” they sang out.

Some longtime devotees, such as Sharda, have no doubt about the trajectory. “Modi came, and during these 11 years there has been a renaissance of Hindu society, a sense of feeling proud of being Hindu, while earlier we were made to feel ashamed,” he said. “The future for India looks great and the RSS is doing nothing but making India great again. If India is great, the RSS is great.”

Andres Schipani is the FT’s New Delhi correspondent. Jyotsna Singh is the New Delhi reporter

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram