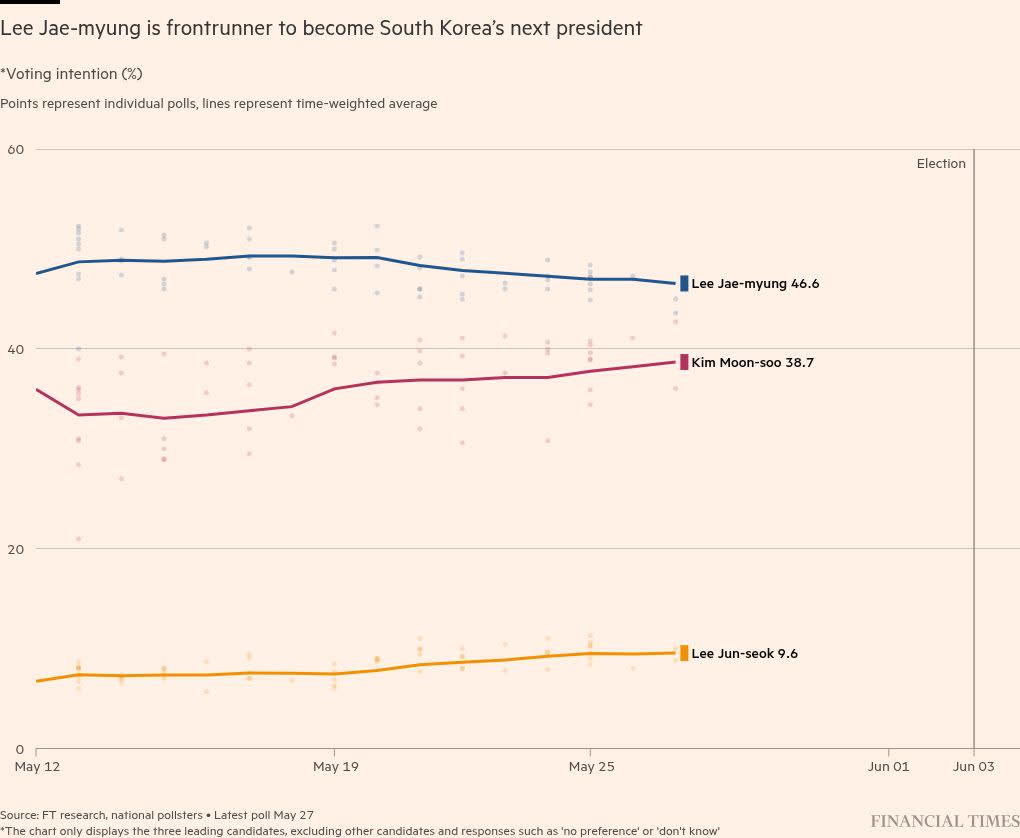

Since losing the last presidential election by a margin of less than 1 per cent, South Korean opposition leader Lee Jae-myung has endured a barrage of criminal indictments and an assassination attempt. Now, he stands on the brink of victory.

Opinion polls show the pugnacious leftwing former factory worker — who has campaigned in a bulletproof jacket — leading his rightwing rival Kim Moon-soo by a comfortable margin ahead of Tuesday’s presidential election, which is likely to have far-reaching implications for South Korea’s democracy and its relations with the US, China and Japan.

It follows a prolonged political crisis after rightwing president Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law last year, leading to his ousting from office. The country is on its third interim leader in less than six months.

Lee’s supporters see him as a warrior ready to dismantle the remnants of the country’s old authoritarian order. Critics portray him as a dangerous demagogue whose Democratic party has used its parliamentary majority to intimidate ministers, prosecutors and judges with threats of impeachment.

Lee, who last year survived being knifed in the neck by an assailant determined to stop him becoming the nation’s leader, is now casting himself in the role of national healer.

“I know better than anyone the harms of political retaliation,” he told journalists on Sunday. “That’s why I believe I’m the right person to put an end to divisive politics.”

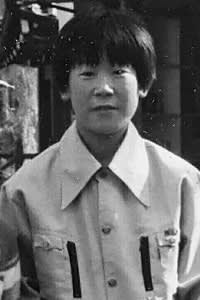

Lee, who grew up in poverty and suffered permanent injury at the age of 13 when his arm was crushed in a machine at the baseball glove factory where he worked, in 2022 declared his ambition to be a “successful Bernie Sanders”.

But since Yoon’s impeachment in December he has tacked sharply to the centre, even describing himself as a “conservative” to appeal to moderate voters. He has emphasised “corporate growth” and conceded that longer working hours may be necessary in some sectors.

Darcie Draudt-Véjares, an expert in South Korean politics at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said Lee’s effort to portray himself “not as a populist tribune of the left but as a centrist champion of economic revitalisation has raised questions as to whether his repositioning is a genuine strategic pivot or a temporary campaign tactic”.

Lee has had frequent brushes with the law, including convictions for drink driving and a long-running investigation into a controversial property development during his time as a city mayor.

His legal troubles intensified following Yoon’s election. Current cases include indictments for misuse of public funds, making false statements during an election campaign, and involvement in an alleged scheme to siphon money to North Korea through an underwear manufacturer in order to win an invitation to Pyongyang.

Lee strongly denies all the charges against him. Legal experts say that, while the processes are still technically continuing, he would be unlikely to be convicted on any of the charges as president.

John Lee, an analyst at Seoul-based information service Korea Pro, said the charges against Lee Jae-myung during Yoon’s presidency helped him to portray himself as a victim of a conservative-dominated “deep state”.

“Previous leftwing presidents have tended to be genteel, scholarly types who tried but failed to rise above the rough and tumble of Korean politics,” he said. “The fact that Lee is a brawler is intrinsic to his appeal.”

Yoon’s impeachment and the disarray of the conservatives “looks to have handed Lee the presidency on a silver platter”, he said.

Leftwing presidents in South Korea have historically been more sceptical than their conservative counterparts about co-operating with the US and Japan, while being more enthusiastic about engagement with North Korea and China.

Lee has been accused by his conservative opponents of “pro-China toadyism” for insisting that South Korea has no direct interest in the outcome of a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

“We should not neglect ties with China or Russia,” Lee said during a presidential debate this week. “There’s no need to have an unnecessarily hostile approach like now.”

Lee has tried to allay fears of an anti-US turn by promising a “stabilisation” of bilateral ties with Washington shaken by the impeachment of the strongly pro-US Yoon.

His appointment of Kim Hyun-chong, a hard-nosed former trade negotiator and national security official, as a key aide suggests he could adopt a tough stance in trade negotiations with Trump, analysts say.

The new South Korean president will have to navigate Washington’s desire to reconfigure their defence relationship to focus less on deterring North Korea and more on China.

Daniel Sneider, a lecturer in East Asian studies at Stanford University, said that, although under Lee South Korea was “more likely to stand up to the Americans”, fears in some US policy circles that he would adopt an overtly pro-China policy were overblown.

Relations with Japan, which improved dramatically after a diplomatic rapprochement between Yoon and Japan’s then-prime minister Fumio Kishida, were likely to suffer, Sneider said.

Lee denounced a summit between Yoon and Kishida in 2023 as “the most humiliating and dreadful moment in the history of our diplomacy”.

But Sneider added that did not mean Lee “cannot engage with Tokyo practically”, noting the two neighbours might yet be brought closer by Trump’s aggressive trade policy.

Given the turmoil at home and an increasingly deteriorating economic and security environment abroad, a unifier might not be what many South Korean voters are looking for, John Lee of Korea Pro.

“Even for those who think Lee is a bit of a gangster, they may conclude that a gangster is exactly what we need right now,” he said.