Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is a senior fellow at King’s College London

On May 7, Indian jets targeted several sites deep inside Pakistan, killing 31 people according to Islamabad. The attack was expected, especially given that India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi promised to punish the perpetrators of the April assault that killed 26 civilians inside Indian-administered Kashmir. Now, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif has authorised his army chief to retaliate.

However, a further response runs the risk of escalating tension to a boiling point between the two nuclear-armed neighbours. This is happening at a time when geopolitical alliances are in flux. Unlike in past India-Pakistan wars when great powers restrained the warring parties, no one is seeking to hold them back now.

The US isn’t acting forcefully to lower the temperature between New Delhi and Islamabad. Although Donald Trump has offered his mediation services, there is no rush of senior US officials to the region. The rowdy boys have been left to fight alone with no headmaster present to march them to their respective corners. Other actors like Saudi Arabia and the UK may urge de-escalation but that won’t have the same effect as pressure from Washington.

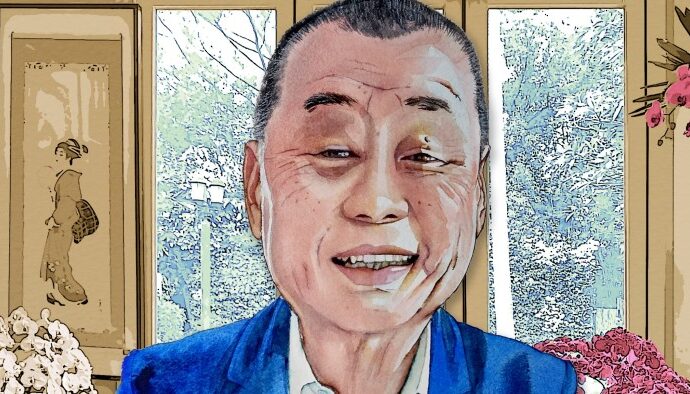

In Pakistan, the public — unaware of militant training camps in their midst and conditioned to see Pakistan as the victim — is clamouring for retaliation. Whatever happens next will depend on one man: the country’s army chief, Asim Munir. Munir controls Pakistan’s strategic decision-making far more than the elected government led by Sharif. And he is not a figure known for his restraint.

One of the reasons that New Delhi believes that Pakistan-based militants were behind the April attack is because of a speech that Munir delivered a week earlier. In it, he referred to Kashmir as Pakistan’s “jugular vein” and vowed not to leave Kashmiris alone in their struggle for independence from India.

He also expressed the polarising view that Pakistan came into being in 1947 because the Hindus and Muslims of the subcontinent could not live together. In so doing, Munir has departed dramatically from the outlook of his predecessor, Qamar Javed Bajwa, who in 2021 spoke about burying the hatchet with India, mainly because in his estimation Pakistan couldn’t afford to fight a war.

Munir was once Bajwa’s head of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the military’s prime intelligence agency. Back then, he didn’t contradict his boss. Now that he’s in charge, he seems intent on taking the military back to its old posture of vying for control of Kashmir and treating India as the prime enemy.

Munir has a reputation for hewing to his religious and ideological beliefs and disliking being challenged. Indeed, some of his older colleagues recall him leaving the room when contradicted, even during informal conversations among officers.

He is now seeking to play the role of strongman in a country that has been riven by political divisions in recent years. Many Pakistani voters suspect Munir of manipulating the 2024 elections and helping to force the cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan out of power. The ongoing conflict with India may have rehabilitated his image temporarily but, given the defence establishment’s dominance of the country’s institutions, it will also put pressure on him to prove the military’s might — in a real conflict against a larger neighbour at a time when the country is under huge economic pressure.

Controlling everything from politics to the economy makes Munir a powerful man, but he’s not a magician who can rescue Pakistan from its economic troubles. A war that pits him against Narendra Modi, another nationalist strongman, will complicate matters even more. The decision Munir must take now is whether to seek a dialogue with India to end the conflict — or get sucked into a greater strategic abyss.