Human efforts to protect the eggs of green sea turtles from predators on a remote Taiwanese island appear to have backfired, according to a two-decade-long study.

The conservation effort on Orchid Island off the southeast coast of Taiwan, which involved fencing off snakes to prevent them from preying on the turtle eggs, instead forced the predators to resort to hunting other reptiles, potentially collapsing the lizard population, according to researchers.

The significant drop in lizard populations revealed the unintended consequences that could result from conservation efforts focused on a single species, highlighting the importance of developing more comprehensive solutions.

China the top destination for trafficked sea turtles, study finds

China the top destination for trafficked sea turtles, study finds

“When this subsidy was removed, these snakes shifted into other habitats for alternative prey, perhaps driving the widespread decline of those lizard species vulnerable to egg predation,” the team wrote.

Orchid Island is a 45 sq km (17.4 square mile) volcanic land mass that has long provided sea turtles a nesting refuge, and the flourishing kukri snake population an abundant food source, helping to transfer nutrients from the ocean to the land.

According to the WWF, green sea turtles are one of the largest sea turtles and are threatened by overharvesting of their eggs, hunting of adults, being caught in fishing gear and loss of nesting beach sites.

Gradual, climate-driven beach erosion, along with a series of unusually strong storms in 2001, has left a small beach named Badai Beach the only remaining site suitable for sea turtle nesting.

But faced with an abrupt loss of access to sea turtle eggs, predatory snakes turned their attention inland to feed on the eggs of forest lizards, resulting in significant population declines of most terrestrial reptile species.

The scientists estimated kukri snakes consumed around 120 sea turtle eggs each year before 2001, which would be equivalent to between 5,000 and 18,000 lizard eggs from the five soft-shelled lizard species on the island.

The team found that while populations of kukri snakes and stink ratsnakes were estimated to have declined by 12 per cent and 8 per cent per year between 1997 and 2020, lizard species saw drops of 11 to 25 per cent every year.

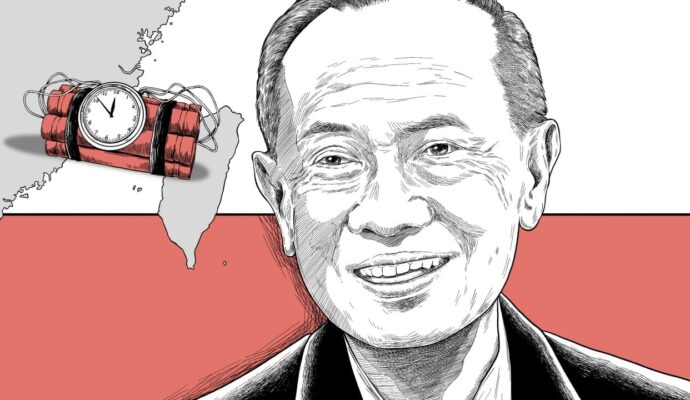

Lead author Huang Wen-san, academic deputy director of the National Museum of Natural Science in Taichung, said the 10 dozen turtle eggs eaten each year account for a small fraction of sea turtle eggs laid and do not amount to a devastating threat to the sea turtle population.

However, having thousands of lizard eggs eaten is a huge loss for any lizard group, leading to a sharp decline in their population, he added.

“After evaluating the predatory behaviour of snakes and the dynamic relationship of the number of turtle eggs and lizards, allowing snake predators to consume turtle eggs moderately might better help conserve the overall ecology of Orchid Island,” he said.

While acknowledging the need to protect the endangered green sea turtles, the team also cited previous studies which showed that conservation efforts targeting adults are more effective than those protecting eggs because of the extremely high mortality of eggs and hatchlings.

Failure to prosecute Japan turtle killers may embolden culprits: activists

Failure to prosecute Japan turtle killers may embolden culprits: activists

According to the US National Ocean Service, a female sea turtle returns to the nesting beach where she was born to lay eggs – up to 100 eggs in a nest.

Hatchlings must escape predators on the beach – such as birds, crabs and raccoons – to make it to the sea. Seabirds and fish will also pursue them in the water. It is estimated only one in 1,000 to one in 10,000 hatchlings survive to adulthood.