To be fair to Modi, his government’s economic performance is respectable after decades of stagnation and disappointment. India’s gross domestic product has grown by about 6 per cent every year on average since 2014, reaching an all-time high of 9.1 per cent last year – impressive in light of the upheavals of the Covid-19 pandemic and recession in many parts of the world.

But a wide range of structural reforms are needed if India is to escape the shackles of its economic past. These include the grip of caste, bureaucratic friction, impenetrable tax rules, still-chronic protection of local business magnates and import tariffs that are among the world’s highest.

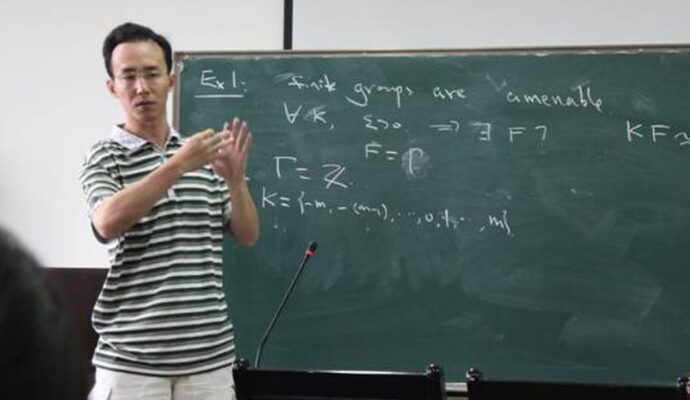

A woman carries water in a slum on Independence Day in Hyderabad, India, on August 15. Modi said India’s economy would be among the top three in the world within five years, as he marked 76 years of independence from British rule. Photo: AP

Any country rising from such a low base must recognise that it will take many decades to achieve anything the late Lee would regard as parity with China – and that this is nothing to be ashamed of. Goldman Sachs predicted last month that by 2075, China would become the world’s largest economy (US$57 trillion), with India (at US$52.5 trillion) overtaking the US (at US$51.5 trillion).

Columbia University’s Arvind Panagariya has similar projections, calculating recently in Time magazine that if India’s real GDP grew at 8 per cent a year into the 2040s and 5 per cent after that, and if the US continues to grow on average by 2 per cent a year, India would overtake the US in 2073.

These are big “ifs”, even for those brave enough to make forecasts a half-century away. And huge bodies of data point India towards a more humdrum trajectory. According to Allison in Foreign Policy, back in 2000, China and India had economies worth less than US$2 trillion each. It took China five years to pass the mark and India 14 years. Last year, India’s economy was worth US$3.4 trillion – a fraction of China’s US$18.3 trillion.

It will take many years of stellar economic growth for India to begin matching China in economic importance, and no amount of miraculous thinking or “China plus one” investment is likely to accelerate that.

Also, many other important economic indicators remain problematic. India accounted for about 1 per cent of global manufacturing in 2000, compared with 7 per cent for China. By last year, India’s share had grown to 3 per cent against China’s 31 per cent. In 2000, India accounted for just 1 per cent of the world’s exports, and China 2 per cent. By last year, China accounted for 15 per cent of global exports against India’s share of 2 per cent.