To understand the crisis gripping China’s real estate sector, it is worth looking into its past. In the first 50 years of the People’s Republic, China did not have a property market as such, as urban residents relied on state employers to provide housing. There were no private developers as all urban land is “owned by the state” under the constitution.

China’s real estate sector started to take off in the late 1980s, when Hong Kong professionals advised mainland Chinese officials in Shenzhen and Shanghai that they borrow a page from the then British colony to sell “land use rights” to investors as part of a long-term lease. Chinese municipal governments immediately lapped up the idea, finding it an excellent source to raise much-needed funds.

China officially kickstarted its real estate market nationwide in 1998, when urban households were allowed to buy and own flats, unleashing a spectacular property market boom thanks to the nation’s rapid urbanisation. Hundreds of millions of people moved into new flats, and property quickly became the most important engine of China’s economic growth.

Chinese municipal authorities became big winners in the process as they realised overnight they were sitting on massive amounts of wealth. “State-owned” land suddenly became sellable and every single local government jumped on the bandwagon.

In the beginning, it created a positive loop: the more land a local government sold, the more money it could raise for its own development, which in turn could be used to improve infrastructure, pushing up land prices further.

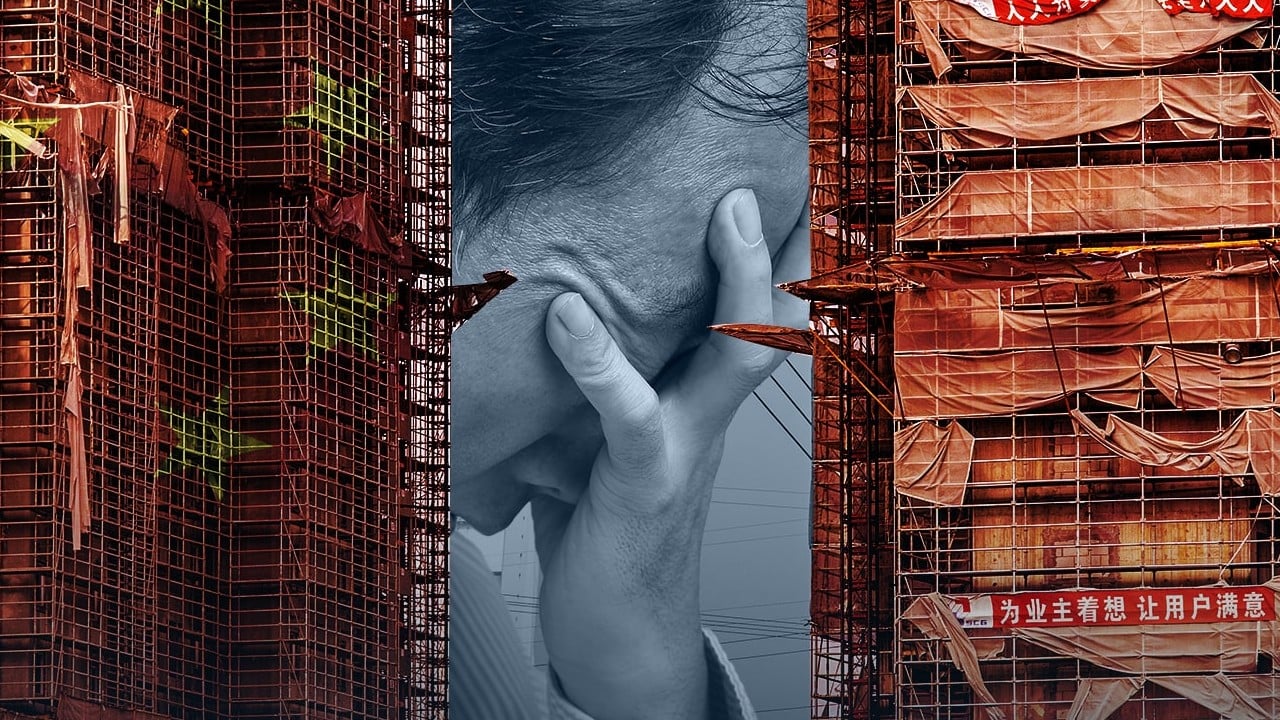

In a very short period of time, China’s urban landscape was permanently changed. In some extreme cases, municipal governments flattened entire old neighbourhoods to build new ones, making “monetisation” of land the underlying reason for such urbanisation projects.

Advertisement

Chinese urban households also benefited from the changes sweeping the landscape. Those who already owned urban flats, whether inherited or allocated by the state, reaped a financial windfall as the steep increase in property prices expanded household wealth.

Top Chinese developers’ sales spiral as they await steps to ease pain

Top Chinese developers’ sales spiral as they await steps to ease pain

According to a survey last year, property accounted for more than 70 per cent of “household wealth” in China. In top Chinese cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen, an owner of a flat, however shabby, is a multimillionaire, at least on paper.

The property boom also underpinned the financialisation of China’s economy. The banking industry boomed, leading to the mushrooming of financial products backed by property. It is worth noting that the bonds of many Chinese local government financial vehicles are ultimately backed by underlying property values.

It is an underestimation to simply say that property accounts for 30 per cent of China’s gross domestic product. To an extent, the complexities of land-finance is at the very core that has driven China’s economic miracle.

Will cutting China’s mortgage rates ease household burdens, free spending power?

Will cutting China’s mortgage rates ease household burdens, free spending power?

The exuberance, however, is fragile because it can only be sustained by continuously rising housing prices. When demand – including “real demand” to improve housing conditions or investment on expectation of asset appreciation – dries up, prices will start to fall and the whole economic structure will start to crumble. Beijing realised this many years ago when it warned that housing prices “can’t grow into the sky”.

Advertisement

One big problem resulting from China’s housing market boom was that it made excessive borrowing possible, and all players, including local governments, developers and households, accumulated debt at an astonishing rate.

For many local governments, they are technically bankrupt. For households, debt repayment pressure will become heavier as the economy slows down and moves into deflationary territory. For developers, survival will be a struggle, even for the biggest ones, because of their debts.

Advertisement

China probably can avoid a property market crash, but the sector can no longer be the engine that once powered its economy.

Advertisement